The ancient sages, as in the case of the Greeks, were thinkers with a broad spectrum; a single person could be a doctor, mathematician, astronomer and philosopher. This seems impossible today, with the increasing degree of specialization and efforts needed to be an expert in a particular field.

In the case of Hypatia of Alexandria (IV and V centuries) she conducted major scientific work in fields such as mathematics and astronomy. History has been demonstrating the skills of women in science and how they have no intellectual disadvantage compared to men. The gender gap is simply a matter of social roles assigned for centuries to one or another gender.

Hypatia was greatly influenced in the intellectual world by her father Theon, a Greek philosopher and mathematician who was the last director of the Museum of Alexandria. Her father provided her with a liberal education, with Hypatia being known today as the legendary freethinker standing against intolerance.

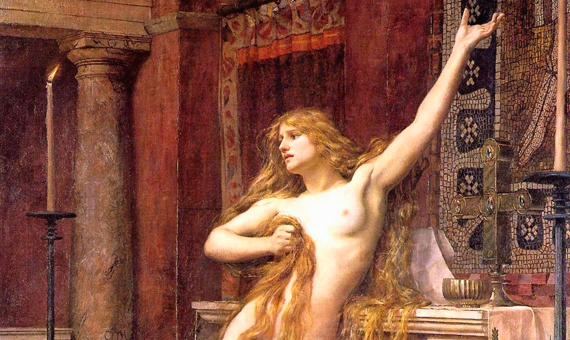

Hypatia was a free woman, educated in the Neo-Platonic school and leader of Neo-Platonic beliefs in Alexandria. She never married; despite her beauty and eloquence, she devoted her life to scientific work.

Her research was reflected in numerous manuscripts, such as “Comments on Diophantus Arithmetic”. Diophantus was a Greek mathematician who lived during the third century and was considered the father of algebra and arithmetic, whose work focused on algebraic equations and number theory. The word Diophantine equations comes from his name. It was in an edition of this book by Diophantus where Pierre de Fermat wrote his famous phrase:

It is impossible to separate a cube into two cubes, or a fourth power into two fourth powers, or in general, any power higher than the second, into two like powers. I have discovered a truly marvellous proof of this , which this margin is too narrow to contain.

Another of her contributions was the release of “Euclid’s Elements”, with comments from her father, Theon, an expert in Euclidean work. Euclid’s Elements is the book with the most editions after the Bible, and includes a complete treatise on geometry.

She also rewrote a treatise on the “Conics” of Apollonius. Her reinterpretations simplified Apollonius’s concepts, by using more accessible language and making it a manual that is easy to follow by the interested reader.

Unfortunately, many of Hypatia’s contributions were lost. Thanks to her correspondence with her student Sinesio de Cirene (later the Bishop of Ptolemais), we know many of her other contributions. Sinesio de Cirene shared a taste for mathematics and astronomy with his tutor, but took another direction, becoming a philosopher-bishop. Sinesio puts on record Hypatia’s uniqueness as an intellectual. He claims her authorship in the construction of an astrolabe, a hydrometer and a hydroscope.

An astrolabe is an instrument constructed to determine the positioning of the stars in the sky and served as a guide for sailors, engineers and architects to determine distances by triangulation. A curious fact is the use of this instrument by Muslim sailors, with which they were guided to determine the position of Mecca so they could pray.

Hypatia also stood out for her skills as a speaker and for being a follower of Neo-pythagoreanism and Neo-platonism; she became an eminent teacher of mathematics, giving classes in her home to a select group of both pagan and Christian aristocrats. Her intelligence took her to the post of adviser to Orestes, prefect of the Eastern Roman Empire, a former pupil.

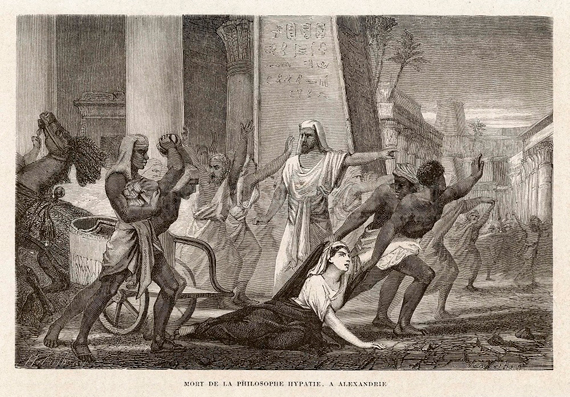

Hypatia’s special nature, treating all her pupils equally, educated from tolerance and rationality, sparked a series of jealousies that resulted in her having many enemies. As a pagan, a supporter of Greek scientific rationalism and an influential political figure, a friend of Orestes, she suffered the intense hostility between Cyril (Christian fanatic, bishop of Alexandria) and Orestes. The accusations against her of blasphemy and anti-Christian sentiment, simply because she refused to betray her ideals and abandon paganism, led to her being ambushed by Bishop Cyril and dragged to the masses where she was brutally murdered.

However, Hypatia never proclaimed her dislike of Christianity. Simply, with her open nature she accepted any pupil, regardless of their religious beliefs.

Hypatia had an interesting life. The life of a strong woman, fighting for her ideals and where she studied science during times in which women were denied access to knowledge. She is portrayed in this way in the recent movie “Agora”, directed by Alejandro Amenábar in 2009, where Hypatia appears engrossed in Euclid’s Elements, the Conics of Apollonius and Aristarchus of Samos’s heliocentric system. In addition, she is presented as a teacher of astronomy, in a class that raises the questions: Why do stars fall? Why do they only rotate from west to east? Why, instead, does a handkerchief fall to the ground on earth? The students respond and Hypatia analyzes their answers and explains from a Ptolemaic view: “Stars do not fall because they are in a circle. They fall on earth because it is the center of the universe”.

You can read the original text in the blog “Matemáticas y sus fronteras” of Fundación madri+d.

Manuel de León

(CSIC, founder of ICMAT, Real Academia de Ciencias, Real Academia Canaria de Ciencias, ICSU)

and

Cristina Sardón

(ICMAT-CSIC).

Comments on this publication