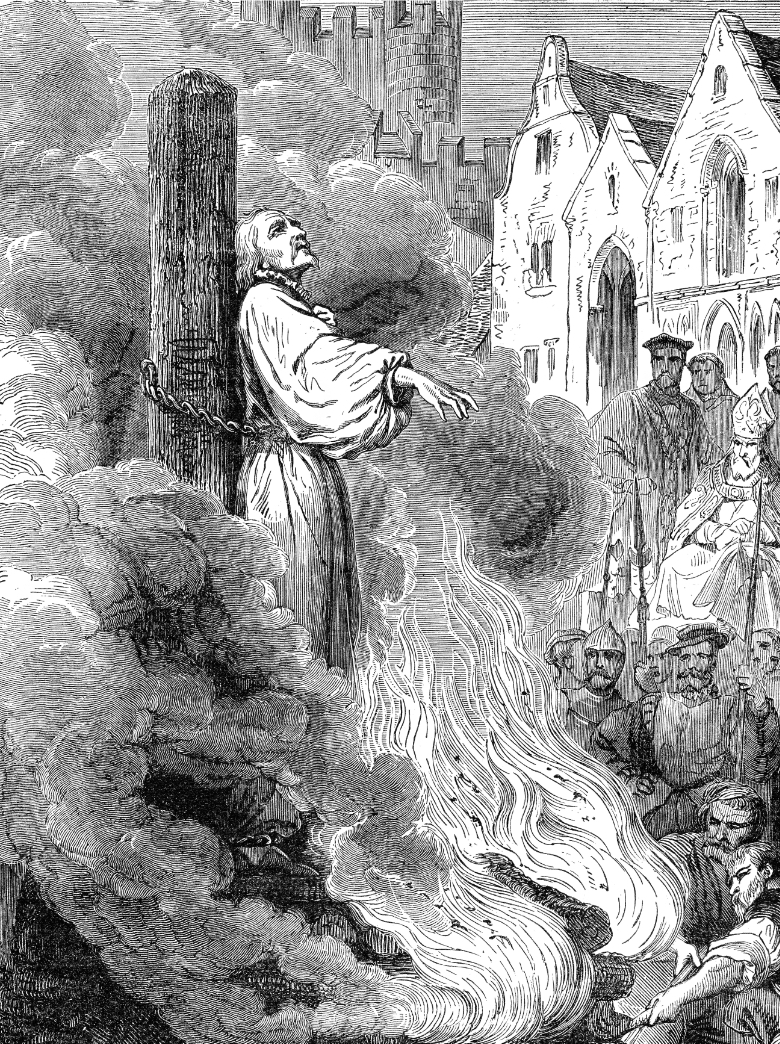

Death by burning at the stake has been a popular method of execution throughout human history, and often the cause of this cruel punishment has been religious heresy or dissent of thought. Such was the case in 1553 of the Spanish theologian Michael Servetus (Spanish: Miguel Servet), the discoverer of pulmonary blood circulation, who was condemned for his theological doctrine. September 20 marks the World Day for Freedom of Expression of Thought, an occasion to defend this fundamental right enshrined in 1948 by the United Nations and which continues to be violated in many countries today. But among so many figures repressed for their ideas, Servetus is perhaps a unique case: his thought crime was considered so serious that he was burned not once, but three times, two of them symbolically.

Much is unknown about the tragic figure of Servetus (29 September 1511 – 27 October 1553), starting with his origins and even his real name. Rather than a historical fact, the proposed date for his birth is because 29 September is Saint Michael’s Day, and it is a Catholic tradition to choose the name of newborns according to the calendar of saints. Historians debate whether he was born in Villanueva de Sigena (Aragon) or in Tudela (Navarre), and whether his change of surname to De Villanueva after his first persecution was a return to his real surname or a tribute to his homeland. In other words, as summarised by the historian and physician Francisco Javier González Echeverría, it is not clear if the persecuted man was Michael de Villanueva, alias Servetus, born in Tudela; or if he was Michael Servetus, and wanted to mark his origin in Villanueva de Sigena.

The trajectory of his life was also peculiar. At the age of just 15 he left Spain to study law in France, where he would live most of his life. He travelled through Europe thanks to his work as secretary of the Franciscan friar Juan de Quintana, who became confessor and advisor to the Emperor Charles V. It was then, shocked by the luxury and corruption of the papacy, that he embraced the Protestant Reformation led by Luther.

However, he went much further in his propositions to what the Reformation tolerated. He studied the Bible in Hebrew and Greek, coming to the conviction that the official translation in Latin had distorted the doctrine. In 1531, he published his first book, whose title did not hide his intentions: in De Trinitatis Erroribus he challenged the dogma of the Trinity, which set both Catholics and Protestants against him. After changing his last name he went to Paris, where he studied medicine while teaching mathematics and astronomy.

The first to understand respiration

In Paris, Servetus inherited the position of assistant dissector from the famous anatomist Andreas Vesalius. His knowledge of the work of Galen—the Greco-Roman physician whose theories prevailed at the time—was unrivalled. But once again he became entangled in problems: after a dispute with the university authorities, he emigrated again and settled in Vienne (in the southeast of France), where he worked as a doctor and proof-reader.

At that time he entered into correspondence with Calvin, who led the Protestant Reformation in Geneva. However, the relationship was soon cut short; Servetus’ ideas so exasperated Calvin that he decided to ignore him, but in 1546 he wrote in a letter to a friend: “If [Servetus] comes here, if my authority is worth anything, I will never permit him to depart alive.”

Finally, in 1553, Servetus published his most famous work, Christianismi Restitutio, a treatise on theology that nevertheless contained his investigations into medicine, since for him physiology revealed the divine connection of the human being. “He who really understands what is involved in the breathing of man has already sensed the breath of God and thereby saved his soul,” he wrote.

And indeed, Servetus was the first author in the West to understand respiration. Until then, Galen’s theory had prevailed, according to which air travelled to the heart through the pulmonary vein to mix with blood, which then crossed from one ventricle to another through pores to be distributed throughout the organism. Servetus proposed instead that the pulmonary artery carried the blood to the lungs not only to nourish these organs, but also to collect air through capillaries, and the blood then returned through the pulmonary vein to the heart. In other words, there was no communication between the ventricles, something that Vesalius had already questioned; the blood passed from one to the other just prior to circulation through the lungs for aeration.

Condemned for his theological doctrine

Servetus’s theory, which proved correct, was met with a deafening silence, perhaps because it was published in a theological volume in which he related the circulation of the blood to the dissemination of the soul through the body, but also because his works were burned at his death. The Italian professor of anatomy and surgeon Realdo Colombo would also correctly describe the pulmonary circulation in his posthumous work De Re Anatomica, published six years after Servetus’s death, but it would not be until the seventeenth century that this knowledge would be firmly established with the works of the Englishman William Harvey.

On the contrary, it was Servetus’s theological doctrine that caused an uproar and led to his persecution, mainly because of his denial of the Trinity and his rejection of infant baptism. Condemned by the Catholic Inquisition, he fled Vienne, where his persecutors had to settle for burning his effigy along with some empty books. But for some inexplicable reason, on his way to southern Italy, he decided to stop in Geneva. There he was recognised, accused and sentenced to be burned at the stake.

Although it was Calvin himself who had encouraged the persecution of Servetus and who had ordered his execution, he tried to have his sentence of death by burning changed to a more pious beheading, but to no avail; the court, presided over by a faction opposed to Calvin, upheld the sentence, and on 27 October 1553, Servetus was burned with a copy of his work tied to his arm.

Servetus would be burned in effigy a third time. According to the Filosofía en Español project of the Gustavo Bueno Foundation, in 1902 the Barcelona essayist and writer Pompeu Gener proposed at the International Congress of Freethinkers, held in Geneva, that a monument to Servetus be erected in Champel, the place in the Swiss city where the theologian and physician was executed. Faced with opposition from the Geneva City Council, which limited itself to erecting a commemorative plaque defending freedom of conscience and atoning for Calvin’s error, the statue of Servetus suffering in prison, the work of the Genevan artist Clotilde Roch, was finally erected in 1908 in Annemasse, a few kilometres from Geneva but on French territory.

However, the statue would not survive another modern inquisition, that of the Nazis. On 13 September 1941, the French Vichy government, which collaborated with the Nazi occupation, removed the bronze sculpture and melted it down. Although this was a common practice aimed at obtaining metal for the manufacture of cannons, it is said that the French Resistance placed a ribbon on the monument—whether before or after its destruction is unknown—which read: “To Michael Servetus, first victim of fascism.” The statue was finally restored in 1960 in a park in Annemasse.

Although it is difficult to be 100% certain that this third burning of Servetus, like the previous two, was ideologically motivated, experts on his person and work have highlighted his role as an “apostle of freedom of thought”, as the inscription at the base of his statue in Annemasse reads. For the Spanish philosopher Angel Alcala, the search for truth and the right to freedom of conscience are the two great legacies of Servetus. And according to the American Marian Hillar, “from a historical perspective, Servetus died in order that freedom of conscience could become a civil right of the individual in modern society.”

Comments on this publication