Some people are blessed with the opportunity to give their name to a great ship. Others are lucky enough to leave it for posterity in the scientific naming of one or more biological species. The Galician oceanographer Ángeles Alvariño enjoys both of these honours, but also a rarer and more exclusive one: she is one of only four Spaniards—and the only woman—to have made the list of the 1,000 most influential scientists in history, according to the Encyclopedia of World Scientists. In addition to these rather anecdotal facts, she has a long list of formal recognitions, which raises the question: how is it possible that someone who shares the podium of Spanish science with greats such as Santiago Ramón y Cajal or Severo Ochoa is still mostly unknown in her country? “Sometimes she had the satisfaction of being recognised, and sometimes not”, said Ángeles Leira Alvariño, the scientist’s daughter, in an interview in 2021.

María de los Ángeles Alvariño González (3 October 1916 – 29 May 2005) was a village girl, born in a parish in the municipality of Ferrol, A Coruña, in the northwest corner of Spain. Her world was small, but her curiosity was immense. It is said that by the age of three she already knew how to read, and then she began to absorb her parents’ knowledge: music and solfeggio from her pianist mother, and science from her country doctor father. In a 2018 interview, Alvariño’s daughter said that her mother was drawn to medicine, but that her father dissuaded her because of how cruel it would be for a woman to watch the sick die. And so, while browsing through the family library, she discovered the next best option, biology.

A Renaissance woman

But as a Renaissance woman, as her daughter defines her, from an early age she wanted to continue to cultivate her many interests. And so, in 1933, when she graduated with a bachelor’s degree in Science and Literature from the University of Santiago de Compostela, she did so with two works that showed her dual interest in science and the humanities: Los insectos sociales (Social Insects) and Las mujeres en el Quijote (The Women in Don Quixote). In the latter, she also indicated what would be another of her pursuits, the promotion of the advancement of women in society.

With her bachelor’s degree in hand, the next stage of her life was to begin studying Natural Science in Madrid. But the Civil War intervened, and the classrooms shut their doors. Back in Galicia, she took advantage of the dark period of the war to study languages. Once the war was over, she returned to Madrid, finished her studies and married the military naval engineer Eugenio Leira, whose support facilitated a path that at that time was practically forbidden to women. After a period of teaching in her native Galicia, her husband was posted to Madrid, where Ángeles managed to gain admission to the Spanish Institute of Oceanography (IEO) as a 34-year-old scholarship holder, a meagre concession to her talent and merits in an all-male institution.

The British oceanographic vessel that changed her life

That difficult start turned out to be her big break. Her work and her doctorate were the springboard that launched her to the IEO headquarters in Vigo, where she soon made a name for herself through her research on the biofouling of ship hulls and on zooplankton, the field in which she would make her most significant contributions. But her career had an insurmountable ceiling, as at that time the Franco regime prohibited female researchers from embarking on Spanish oceanographic vessels. And an oceanographer without an ocean was like a fish without fins.

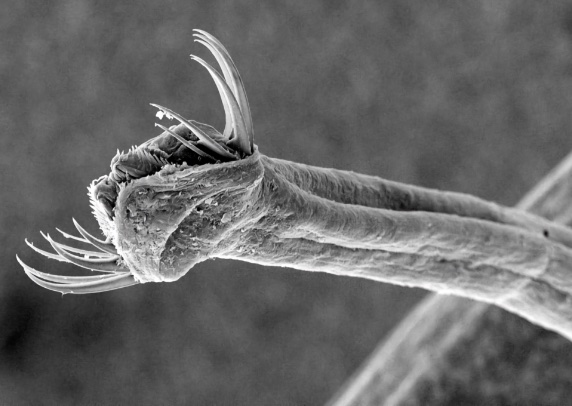

It was then that the opportunity arose for her to greatly advance her career, which necessarily involved emigration. In 1953, a British Council grant opened the doors of the Marine Biological Association laboratory based in Plymouth, England. Her mentor there, Frederick S. Russell, offered her a unique opportunity to become the first woman researcher to join the crew of a British oceanographic vessel. Alvariño more than rose to the challenge: during her many voyages she deepened her knowledge of zooplankton and ichthyoplankton—the larvae and eggs of fish. Her research on chaetognaths, or arrow worms, led to the discovery of an anomaly in the distribution of plankton species that revealed an unusual movement in the waters of the Atlantic. During this first stay abroad, her husband remained in Spain looking after their daughter. He always recognised her worth and remained in her shadow, encouraging her and supporting her work.

After her British adventure she returned to Spain, but not for long. With the growth of her reputation abroad, the appeal of pursuing her career in her native country, where her options were limited, faded, so in 1956 a US exchange grant from the Fulbright Program took her across the Atlantic with her daughter—her husband remained in Spain—to join the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution in Massachusetts under the direction of oceanographer and military officer Mary Sears, a world authority on zooplankton. Sears later facilitated her move to the Scripps Institution of Oceanography, in La Jolla (California), after another visit to Spain.

Fighting discrimination against women in science

Her time at this institution, and later at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), would take her career to a peak, something that was nevertheless ignored back in Spain: in 1966, the Galician newspaper La Noche interviewed her daughter, then a promising young architect based in the USA. In reference to her mother, the journalist limited himself to pointing out that she was a biologist and that she had been “claimed” by the Scripps Institute of Oceanography, which is why the young woman, “a Ferrol native and a Spaniard through and through”, was living in California with her parents. By then Ángeles Alvariño was already an important scientific figure, but her name was not even mentioned.

Yet even in the US, she faced discrimination against women in science. According to her daughter, she resisted tooth and nail attempts by her male colleagues to take credit for her work. She went so far as to file a sex discrimination complaint with the US government because women were denied promotion to higher ranks. At meetings, she felt out of place when men were separated on one side and women on the other—men to talk about science, women about washing machines.

She retired from NOAA in 1987 but continued to work as a scientist emeritus. She died in 2005 in San Diego of leiomyosarcoma, a rare form of cancer, lamenting that she had no more time to continue her research. During her lifetime she received numerous awards and distinctions from organisations such as the United Nations and various universities in the USA and Latin America. Her work included the discovery of 22 new species of chaetognath, siphonophore and jellyfish, as well as research on their ecology, which led to some hundred publications. In recognition of her career, two species were honoured with her surname, the chaetognath Aidanosagitta alvarinoae and the jellyfish Lizzia alvarinoae. One of the IEO’s most modern oceanographic vessels also bears her name, an inspiration for younger generations of women scientists.

In 2018, on the occasion of the inauguration of a monolith in homage to Ángeles Alvariño next to the Casa de las Ciencias in A Coruña, her daughter said that this gesture would have moved her, and that she would even have cried a little, “like a good Galician”. Ángeles Leira recounted that her mother, in addition to her science and her many interests, including research into the natural history of the Malaspina Expedition that she undertook in her final years, also sewed, designed clothes and knitted stockings—a true Renaissance woman, but Galician to the core.

Javier Yanes

Comments on this publication