Few things are as simple and yet as precious and necessary as salt, sodium chloride. We owe much of our civilisation to it, and we have an expression to describe someone who is honest, kind-hearted and reliable: the salt of the earth. But one of the best known health tips, and one of the first things we are advised to do as we get older, is to reduce our salt intake, as its abuse is linked to high blood pressure, cardiovascular disease and other problems. The same is true for our planet: too much salt is bad for its health. And because of human activity, the Earth’s salt is exceeding permissible limits, which is a threat in more ways than we can ever imagine.

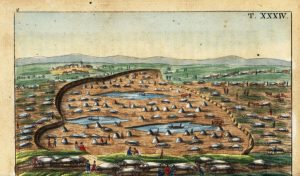

It is impossible to know when humans began using salt as a seasoning. In Europe, the earliest known salt exploitation dates back at least to the Neolithic period, 8,000 years ago, and it has been suggested that the oldest known European town, Solnitsata in present-day Bulgaria, was a centre of salt production. It is no exaggeration to say that our civilisation was built on salt: it is the origin of the word “salary”, it motivated the construction of cities and some of the first Roman roads such as the Via Salaria, and it inspired revolts and struggles for its control. And all this because salt is not only an appetising condiment, but also a way of preserving food, breaking seasonal dependency and allowing food to be transported over long distances.

The main force influencing the global salt cycle

The reason we love salt so much is not just a whim but lies at the very root of our biology: sodium is an essential nutrient for living things, involved in countless cellular and organic processes. It is involved in regulating the body’s homeostasis—the osmotic pressure of cells and tissues—and is an essential signaller for neuronal transmission in the nervous system and muscles. For all these reasons, we cannot do without sodium; a lack of salt can be just as serious as an excess.

So the right amount of salt is not just a culinary matter, it is a question of survival. Salt must be in the right proportions and in the right places: for example, not in the water we use for drinking and food production. Although the Earth’s water is neither created nor destroyed, liquid freshwater accounts for only 0.77% of the total; and since 99% of it is underground, this leaves only 0.0077% of terrestrial water in lakes and rivers, which sustain ecosystems and agriculture, and which are increasingly being degraded by human intervention, with desertification as one of its most serious consequences.

But while humans are now responsible for more than 60% of the variations in the level of the world’s freshwater reserves, as a study using NASA satellite data revealed in 2021, we now know that we are also the main force influencing the global salt cycle. And the results of this management are not exactly optimal: we are salinizing freshwater to levels that pose an “existential threat”.

This is the conclusion of a 2023 scientific review led by the University of Maryland and Virginia Tech. The researchers explain that salt has its own natural terrestrial cycle, “primarily driven by relatively slow geologic and hydrologic processes that bring different salts to the surface of the Earth.” Salts, including not only sodium chloride but also other types, arrive from exposed rock layers, undergoing weathering and transport processes that carry them into the atmosphere and oceans, as well as through living organisms. But “anthropogenic activities have accelerated the processes, timescales and magnitudes of salt fluxes and altered their directionality, creating an anthropogenic salt cycle,” the authors write.

Freshwater salinisation syndrome

This is a result of our insatiable demand for salt: production has skyrocketed in the last century, reaching 300 million tonnes of sodium chloride per year. And we consume it indiscriminately, for example to melt snow and ice in cities and on roads. In the US, the authors estimate, nearly 20 million tonnes of salt are dispersed each year, accounting for 44% of the country’s consumption and 14% of all dissolved solids entering streams.

The excess salt we extract and discharge into the environment is causing what the authors call “freshwater salinisation syndrome”. Its symptoms are alarming: more than 10 million square kilometres worldwide, an area about the size of United States, are suffering from human-induced soil salinisation. Over the last half century, the salinity of rivers has increased. Another study in the US has revealed salinisation of groundwater sources that feed wells.

The result is harm to drinking water, ecosystems and agriculture, but there is more: saline environments corrode infrastructure, including power generation, and saline dust continues to circulate as a pollutant that combines with others and, in the form of aerosols, worsens air quality. The authors of the University of Maryland paper therefore see a need to “identify environmental limits and thresholds for salt ions and reduce salinization before planetary boundaries are exceeded, causing serious or irreversible damage across Earth systems”. As lead author Sujay Kaushal concludes, “it’s about finding the right balance”; a world with just the right amount of salt.

Javier Yanes

Comments on this publication