In June 1947, what had previously been a newsletter published by a group of scientists from the former Manhattan Project at the University of Chicago became a full-fledged magazine with the title Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. That first issue had a simple image on its cover, a clock with its hands set at seven minutes to twelve, with which the Bulletin‘s members wanted to warn of how close humanity was to annihilation—midnight—due to the danger of nuclear war. Since then, the so-called Doomsday Clock has served as a warning and reminder of the global existential threats created by humanity against itself, which today also include climate change and more, while its hands have been moved forward or backward depending on the intensity of the risk. Since 2020, the clock has been set at only 100 seconds to midnight, the closest it has ever been to the end in its entire history.

The Bulletin proudly bears its origins, in which the name of Albert Einstein figures prominently. It was the German physicist who on 2 August 1939 signed a letter—actually penned by his colleague Leo Szilard—to the then US President Franklin Delano Roosevelt, drawing his attention to the possibility of using a nuclear chain reaction in a large mass of uranium to build “extremely powerful bombs of a new type”. The letter concluded by suggesting that the government of Nazi Germany might already be exploring this avenue.

That letter has been called one of the documents that changed the world, and not surprisingly; one month later, World War II broke out. And although Roosevelt’s reaction was not immediate, it was the first step towards what in 1942 would take shape as the Manhattan Project, which in turn led to the nuclear bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in August 1945, ending the global war. The scientists involved were well aware of the ultimate purpose of their work, although many of them opposed its use against civilians and were horrified by the consequences. Einstein, who did not work on the project, also regretted signing the famous letter.

The historical fluctuations of the most famous minute hand

In the month following the bombings in Japan, the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists of Chicago was established to “equip the public, policymakers and scientists with the information needed to reduce man-made threats to our existence.” This goal was embodied in the publication of a newsletter that compiled articles by leading scientists and academics. Alongside its founders, Eugene Rabinowitch and Hyman Goldsmith, the Bulletin brought together a large group of contributors including Einstein and Szilard, along with names such as J. Robert Oppenheimer, Max Born, Hans Bethe and Edward Teller, among others.

In 1947, what had begun as a mimeographed pamphlet was transformed into a printed magazine, with the aim of reaching a wider audience. Its cover illustration was commissioned from artist and Bulletin member Martyl Langsdorf, also the wife of Manhattan Project physicist Alexander Langsdorf. She was the author of the clock’s visual metaphor: set against an attention-grabbing bright orange background, the black-and-white hands placed at seven minutes to midnight suggested a countdown to the annihilation of humanity by nuclear war. According to the Bulletin‘s current president and CEO, Rachel Bronson, Martyl proposed this idea “both because of the urgency that it conveyed and also because of the tick, tick, tick, tick nature of it—that it would move toward midnight unless we could push it the other way.”

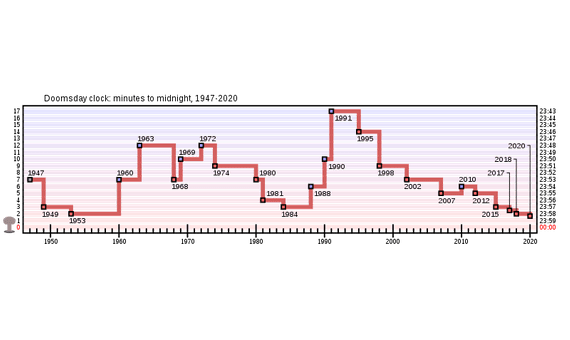

The Doomsday Clock, also sometimes called the Clock of the Final Judgment, became not only the Bulletin‘s emblem, appearing on all its covers, but also an icon of popular culture that has inspired songs, books, films, comics and video games. Each year, the Bulletin‘s board has moved the minute hand to reflect the swings in the severity of the nuclear threat, from two minutes to midnight in 1953, at the height of the Cold War, to 17 minutes in 1991, with the collapse of the Soviet Union and the East-West détente brought about by the signing of the first START nuclear arms reduction treaty.

From nuclear threat to climate apocalypse

But since 1991, the clock has moved almost continuously towards midnight, and not only because of the original threat that inspired its conception. In 2007, the clock underwent a graphic and conceptual redesign; the former, by designer Michael Bierut, sought an adaptation to modern times, and this was also the purpose of the latter by incorporating the great threat of our time—climate change—along with other dangers due to disruptive technologies such as Artificial Intelligence and biological weapons.

Is it appropriate to compare the risk of nuclear war with that of climate change? “Full-out nuclear war, once begun, can cause catastrophic loss of life and societal disruption within hours, whereas the climate catastrophe unfolds over decades to centuries and gets worse each year that we continue to emit carbon dioxide into the atmosphere,” Oxford University climate and planetary physicist Raymond Pierrehumbert, a member of the Bulletin‘s Science and Security Board and co-author of the third report of the UN’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, tells OpenMind. “However, the conditions that make catastrophic climate change more likely—technological developments (both favourable or unfavourable), treaty negotiations, international hostilities, respect for science—develop over the same multi-decade time scale as do the factors governing the risk of nuclear war.”

In other words, the purpose is not so much to warn about the greater or lesser proximity of the disastrous consequences of climate change as about the current state of human action that may accelerate or delay it. Thus, notes Pierrehumbert, “it is appropriate to assess the risks for both nuclear war and climate disruption using the same clock metaphor.” And this perception played a major role in the Bulletin‘s experts placing the hand closer to midnight in 2020 than ever before—100 seconds—an assessment that was also affirmed in the 2021 revision of the clock.

A clock not without its critics

Nevertheless, the Doomsday Clock has also attracted a great deal of criticism. It is not uncommon for it to be the target of condemnation by certain conservative media outlets that accuse it of being politically biased, or by organisations known for their climate change denialist stance. But it has also been criticised by the scientific and academic community for its lack of quantitative rigour due to the arbitrary nature of the position of the minute hand; Martyl initially chose to place the hand at seven minutes because “it looked good,” which has led some to define it as “probabilistic rhetoric” or as a “marketing stunt” that only muddies the message it intends to convey. Even the magazine Physics World considers that the physics community, in whose bosom the clock was born, now feels rather detached from the concept.

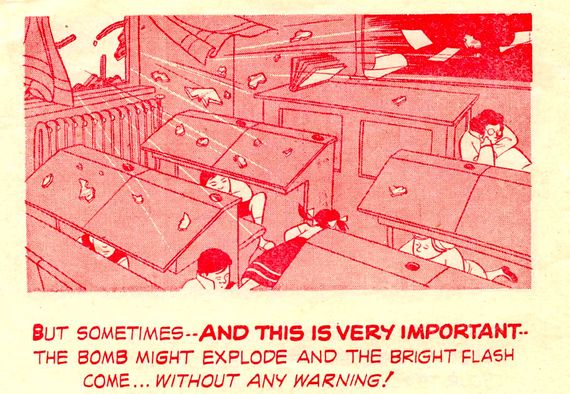

Moreover, in a society that is very different from the one in which the idea was born three quarters of a century ago, in a time when attempts are being made to explain, raise awareness and mobilise people towards positive action rather than frighten them with an apocalyptic spirit that appeals more to visceral fear than to rationality, some experts feel that the Doomsday Clock may not be the most appropriate tool and may even be counterproductive by inciting inaction or apathy when the message is transmitted to generation after generation that we live permanently on the brink of extinction.

All of this becomes even more relevant when one questions how useful the clock has historically been beyond its public image, in terms of its practical contribution to averting the dangers it warns of (Bronson has not responded to OpenMind‘s questions about how the Bulletin rates its achievements in this regard). There have even been warnings that the clock can exacerbate the risks it seeks to avert—as in a self-fulfilling prophecy: “A widespread belief that a nation is under threat can create conditions under which preemptive offensive action is politically feasible and publicly acceptable, exacerbating the likelihood of conflict,” wrote nuclear policy expert Tom Vaughan at Aberystwyth University in The Conversation.

In short, perhaps the concept of the Doomsday Clock has lost its relevance and is now almost as vintage as the analogue technology it represents. But while the current significance of the clock may be up for debate, the threats it warns of are far less so. In the words of Anders Sandberg, an expert in the ethics and society of new technologies at the Future of Humanity Institute at the University of Oxford, “doomsday predictions are rarely informative, but good ones can be directive: they urge us to fix the world.”

Javier Yanes

Comments on this publication