In December 2015, the World Health Organization (WHO) presented its list of humanity’s greatest microscopic enemies: the most worrying emerging pathogens, all of them viruses. In doing so, the WHO drew attention to those infections that are most likely to cause serious outbreaks in the near future, and against which there are few or no medical countermeasures. The aim of this list, which has been subsequently revised twice, is to draw attention to the need to prioritise research and development against these viruses.

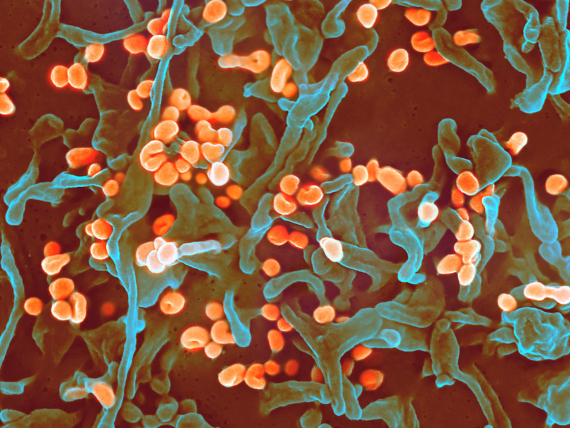

Crimean-Congo haemorrhagic fever

In 1944, Soviet scientists described a viral disease on the Crimean peninsula, but the agent responsible could not be isolated. A quarter of a century later, it was determined that a virus detected in 1956 in the Congo was the same one that caused Crimean disease. The Crimean-Congo haemorrhagic fever virus is transmitted by tick bites, but can also be spread between humans through body fluids. It causes a haemorrhagic fever from which survivors recover in about two weeks, although it is fatal in 10% to 40% of cases according to the WHO, while other sources speak of mortality rates of up to 80%. It is widespread in Africa, Eastern Europe and Asia, where outbreaks occur regularly, although it has also been detected in Western Europe, including Spain and the United Kingdom. None of the vaccines in development have yet been approved. Some experts have warned that tick-borne diseases are expanding their range.

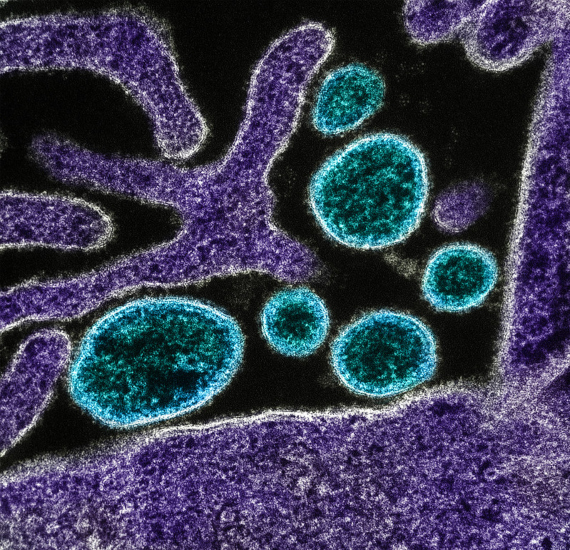

Ebola and Marburg virus diseases

The Ebola virus is already an old acquaintance for much of humanity, since the outbreak that emerged in 2013 in West Africa and affected ten countries. That epidemic ended in 2016 with more than 28,000 cases and the number of deaths exceeding 11,000, resulting in a 40% fatality rate. However, the Ebola virus can cause death in up to 90% of those infected. Its main reservoir is the fruit bat, and human-to-human transmission occurs through body fluids.

At the time of publication of this article, the WHO is awaiting the conclusion of the last outbreak to date, which occurred in the Democratic Republic of Congo in 2018. This latest appearance of the virus has been largely controlled by the approval of a vaccine that began development in Canada years before the 2013 outbreak. However, approval of a vaccine against Marburg virus, a relative of Ebola that causes a similar disease, is still pending.

Lassa fever

Lassa haemorrhagic fever is not a highly lethal disease compared to others on the WHO list, but it is widespread in West Africa where it infects up to half a million people a year, resulting in some 5,000 deaths annually. The vector of transmission of the virus is the rat Mastomys natalensis. People become infected through contact with these animals or with materials contaminated by their urine or faeces, and human-to-human transmission is then possible. About 80% of those infected are asymptomatic, and 1% die.

The disease is especially severe in pregnant women, causing miscarriages in 95% of cases and possible damage to surviving babies. Although it has been known about since the 1950s and the virus was identified in 1969, its status as a virus endemic to Africa has kept it a neglected disease for which a vaccine has not yet been approved.

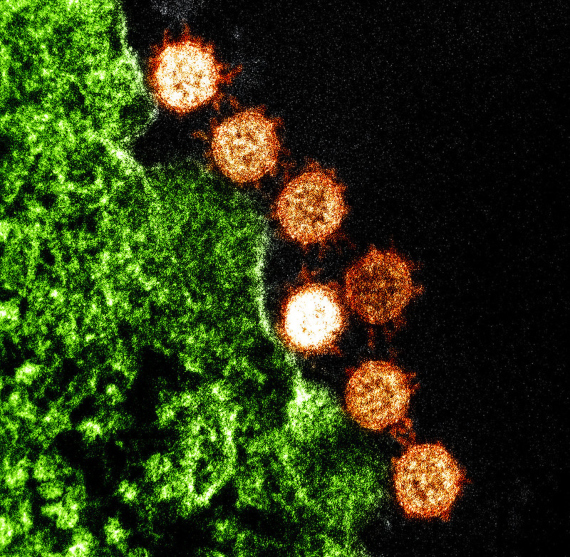

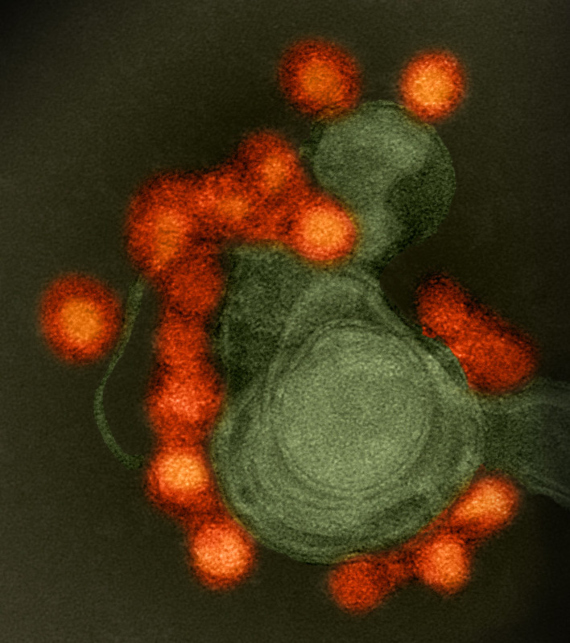

Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS) and Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS)

Although not the first human coronaviruses identified, the SARS and MERS viruses first introduced this class of virus to the general public. SARS made its debut in 2002 in mainland China and Hong Kong, affecting 8,098 people, with 774 deaths. No new cases have appeared since 2004.

In 2012, a new, apparently more lethal coronavirus was found in Saudi Arabia, with a mortality rate of around 35% of confirmed patients. Fortunately, the MERS virus appears to be more difficult to transmit between humans, with outbreaks attributed to contact with animals, especially dromedaries. However, the continuous trickle of MERS cases, the latest to date in January and February this year, shows that the virus continues to spread among its reservoirs. Vaccines against both coronaviruses are currently being tested.

Nipah and henipaviral diseases

The Nipah virus was only discovered relatively recently, in 1999, and the 700 cases reported so far in Asia have not yet led to a specific death rate, estimated at between 40% and 75% of those infected. Added to this is its severity—it can cause a coma within 24 to 48 hours of the onset of symptoms. Although the virus has its reservoir in bats and is spread between humans through direct contact, pigs are a frequent source of transmission. Nipah belongs to the genus Henipavirus, which includes other RNA viruses potentially dangerous to humans and animals. There are as yet no approved vaccines.

Rift Valley Fever

Classified among the mosquito-borne viruses, Rift Valley Fever has caused several outbreaks in Africa and Arabia since the early 20th century, with the potential to spread through Asia and into Europe if the insect carriers spread. The disease wreaks havoc on livestock, and humans can become infected not only from mosquito bites, but also from the blood and organs of animals. Human-to-human transmission has not been documented. Symptoms can range from the mildest flu-like illness to a haemorrhagic fever that is lethal in 50% of cases.

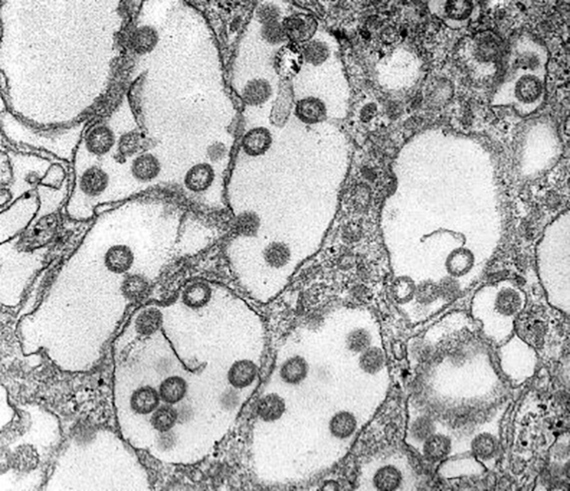

Zika

It has been known about since 1947, but it was in 2015 that the Zika virus made headlines around the world because of the epidemic that began in Brazil and spread through much of the Americas. In particular, Zika caused a wave of panic by causing microcephaly in the foetuses of infected mothers and by its ease of transmission, through the bite of Aedes mosquitoes, which are active during the day. Between 2015 and 2016, one and a half million people in Brazil contracted the virus, with some 3,500 cases of microcephaly recorded. The outbreak began to subside at the end of 2016, but the disease has been reported in 86 countries.

Disease X

Closing off its list, the WHO included a “Disease X”, referring to a new, possibly emerging, yet unknown pathogen that could lead to a serious international epidemic. With this, the organization wants to emphasize the importance of promoting research and development that will allow transversal preparation for future outbreaks of new viruses. Regrettably, the first of these threats has not been long in coming, as the new coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 which causes the coronavirus disease COVID-19 fits within this category.

Comments on this publication