Hyperhistory

More people are alive today than ever before in the evolution of humanity. And more of us live longer(1) and better(2) today than ever before. To a large measure, we owe this to our technologies, at least insofar as we develop and use them intelligently, peacefully, and sustainably.

Sometimes, we may forget how much we owe to flints and wheels, to sparks and ploughs, to engines and satellites. We are reminded of such deep technological debt when we divide human life into prehistory and history. That significant threshold is there to acknowledge that it was the invention and development of information and communication technologies (ICTs) that made all the difference between who we were and who we are. It is only when the lessons learned by past generations began to evolve in a Lamarckian rather than a Darwinian way that humanity entered into history.

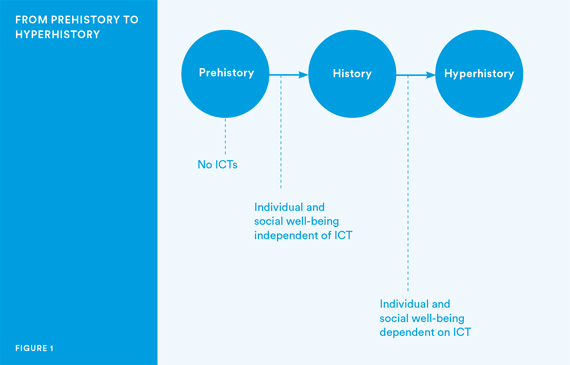

History has lasted six thousand years, since it began with the invention of writing in the fourth millennium BC. During this relatively short time, ICTs have provided the recording and transmitting infrastructure that made the escalation of other technologies possible, with the direct consequence of furthering our dependence on more and more layers of technologies. ICTs became mature in the few centuries between Guttenberg and Turing. Today, we are experiencing a radical transformation in our ICTs that could prove equally significant, for we have started drawing a new threshold between history and a new age, which may aptly be called hyperhistory (Figure 1). Let me explain.

Prehistory (i.e., the period before written records) and history work like adverbs: they tell us how people live, not when or where. From this perspective, human societies currently stretch across three ages, as ways of living. According to reports about an unspecified number of uncontacted tribes in the Amazonian region, there are still some societies that live prehistorically, without ICTs or at least without recorded documents. If one day such tribes disappear, the end of the first chapter of our evolutionary book will have been written. The greatest majority of people today still live historically, in societies that rely on ICTs to record and transmit data of all kinds. In such historical societies, ICTs have not yet overtaken other technologies, especially energy related ones, in terms of their vital importance. Then there are some people around the world who are already living hyperhistorically, in societies or environments where ICTs and their data processing capabilities are the necessary condition for the maintenance and further development of societal welfare, personal well-being, as well as intellectual flourishing. The nature of conflicts provides a sad test for the reliability of this tripartite interpretation of human evolution. Only a society that lives hyperhistorically can be vitally threatened informationally, by a cyber attack. Only those who live by the digit may die by the digit.(3)

To summarize, human evolution may be visualized as a three-stage rocket: in prehistory, there are no ICTs; in history, there are ICTs, they record and transmit data, but human societies depend mainly on other kinds of technologies concerning primary resources and energy; in hyperhistory, there are ICTs, they record, transmit, and, above all, process data, increasingly autonomously, and human societies become vitally dependent on them and on information as a fundamental resource. Added-value moves from being ICT-related to being ICT-dependent. We can no longer unplug our world from ICTs without turning it off.

If all this is even approximately correct, the emergence from its historical age represents one of the most significant steps ever taken by humanity. It certainly opens up a vast horizon of opportunities as well as challenges and difficulties, all essentially driven by the recording, transmitting, and processing powers of ICTs. From synthetic biochemistry to neuroscience, from the Internet of Things to unmanned planetary explorations, from green technologies to new medical treatments, from social media to digital games, from agricultural to financial applications, from economic developments to the energy industry, our activities of discovery, invention, design, control, education, work, socialization, entertainment, care, security, business, and so forth would be not only unfeasible but unthinkable in a purely mechanical, historical context. They have all become hyperhistorical in nature today. It follows that we are witnessing the defining of a macroscopic scenario in which hyperhistory, and the re-ontologization of the infosphere in which we live, are quickly detaching future generations from ours.

Of course, this is not to say that there is no continuity, both backward and forward. Backward, because it is often the case that the deeper a transformation is, the longer and more widely rooted its causes may be. It is only because many different forces have been building the pressure for a very long time that radical changes may happen all of a sudden, perhaps unexpectedly. It is not the last snowflake that breaks the branch of the tree. In our case, it is certainly history that begets hyperhistory. There is no ASCII without the alphabet. Forward, because it is most plausible that historical societies will survive for a long time in the future, not unlike those prehistorical Amazonian tribes mentioned before. Despite globalization, human societies do not parade uniformly forward, in synchronic steps.

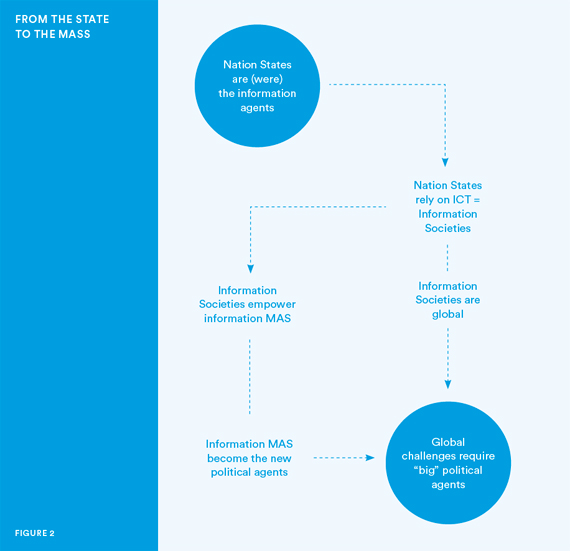

Such a long-term perspective should help to explain the slow and gradual process of political apoptosis that we are undergoing, to borrow a concept from cell biology. Apoptosis (also known as programmed cell death) is a natural and normal form of self-destruction in which a programmed sequence of events leads to the self-elimination of cells. Apoptosis plays a crucial role in developing and maintaining the health of the body. One may see this as a dialectical process of renovation, and use it to describe the development of nation states into information societies in terms of political apoptosis (see Figure 2), in the following way.

Oversimplifying, a quick sketch of the last four hundred years of political history may look like this. The Peace of Westphalia (1648) meant the end of World War Zero, namely the Thirty Years’ War, the Eighty Years’ War, and a long period of other conflicts during which European powers, and the parts of the world they dominated, massacred each other for economic, political, and religious reasons. Christians brought hell to each other with staggering violence and unspeakable horrors. The new system that emerged in those years, the so-called Westphalian order, saw the coming of maturity of sovereign states and then nation states as we still know them today, France, for example. Think of the time between the last chapter of The Three Musketeers—when D’Artagnan, Aramis, Porthos, and Athos take part in Cardinal Richelieu’s siege of La Rochelle in 1628—and the first chapter of Twenty Years Later, when they come together again, under the regency of Queen Anne of Austria (1601–66) and the ruling of Cardinal Mazarin (1602–61). The state became not a monolithic, single-minded, well-coordinated agent, the sort of beast (Hobbes’ Leviathan) or rather robot that a later, mechanical age would incline us to imagine. It never was. Rather, it rose to the role of the binding power, the network able to keep together, influence, and coordinate all the different agents and behaviors falling within the scope of its geographical borders. Citizenship had been discussed in terms of biology (your parents, your gender, your age…) since the early city-states of ancient Greece. It became more flexible (degrees of citizenship) when it was conceptualized in terms of legal status as well, as under the Roman Empire, when acquiring a citizenship (a meaningless idea in purely biological contexts) meant becoming a rights holder.

With the modern state, geography started playing an equally important role, mixing citizenship with nationality and locality. In this sense, the history of the passport is enlightening. As a means to prove one’s own identity, it is acknowledged to be an invention of King Henry V of England (1386–1422), centuries before the Westphalian order took place. However, it is the Westphalian order that makes possible the passport as we understand it today: a document that entitles the holder not to travel (e.g., a visa may also be required) or be protected abroad, but to return to (or be sent back to) the country that issued the passport. It is, metaphorically, an elastic band that ties the holder to a geographical point, no matter how long in space and prolonged in time the journey in other lands is. Such a document became increasingly useful the better that geographical point was defined. Readers may be surprised to know that travelling was still quite passport-free in Europe until World War I, when security pressure and techno-bureaucratic means caught up with the need to disentangle and manage all those elastic bands travelling around by train.

Back to the Westphalian order. Now the physical and legal spaces overlap and they are both governed by sovereign powers, which exercise control through physical force to impose laws and ensure their respect within the national borders. Mapping is not just a matter of travelling and doing business, but also an introvert question of controlling one’s own territory, and an extrovert question of positioning oneself on the globe. The taxman and the general look at those lines with eyes very different from those of today’s users of Expedia. For sovereign states act as multiagent systems (or MASs, more on them later) that can, for example, raise taxes within their borders and contract debts as legal entities (hence our current terminology in terms of “sovereign debt,” which are bonds issued by a national government in a foreign currency), and they can of course dispute borders. Part of the political struggle becomes not just a silent tension between different components of the state-MAS, say the clergy versus the aristocracy, but an explicitly codified balance between the different agents constituting it. In particular, Montesquieu suggests the classic division of the state’s political powers that we take for granted today. The state-MAS organizes itself as a network of three “small worlds”—a legislature, an executive, and a judiciary—among which only some specific kinds of information channels are allowed. Today, we may call this Westphalian 2.0.

With the Westphalian order, modern history becomes the age of the state, and the state becomes the information agent, which legislates on and controls (or at least tries to control), insofar as it is possible, all technological means involved in the information life cycle including education, census, taxes, police records, written laws and rules, press, and intelligence. Already most of the adventures in which D’Artagnan is involved are caused by some secret communication. The state thus ends by fostering the development of ICTs as a means to exercise and maintain political power, social control, and legal force, but in so doing it also undermines its own future as the only, or even the main, information agent. As I shall explain in more detail later, ICTs, as one of the most influential forces that made the state possible and then predominant as a historical driving force in human politics, also contributed to make it less central, in the social, political, and economic life across the world, putting pressure on centralized government in favor of distributed governance and international, global coordination. The state developed by becoming more and more an information society, thus progressively making itself less and less the main information agent. Through the centuries, it moved from being conceived as the ultimate guarantor and defender of a laissez-faire society to a Bismarckian welfare system that would take full care of its citizens. The two World Wars were also clashes of nation states resisting mutual coordination and inclusion as part of larger multiagent systems. They led to the emergence of MASs such as the League of Nations, the World Bank, the International Monetary Fund, the United Nations, the European Union, NATO, and so forth. Today, we know that global problems—from the environment to the financial crisis, from social justice to intolerant religious fundamentalisms, from peace to health conditions—cannot rely on nation states as the only sources of a solution because they involve and require global agents. However, in a post-Westphalian world (Linklater, 1998), there is much uncertainty about the new MASs involved in shaping humanity’s present and future.

The previous remarks offer a philosophical way of interpreting the Washington Consensus, the last stage in the state’s political apoptosis. John Williamson coined the expression “Washington Consensus” in 1989, in order to refer to a set of ten specific policy recommendations that he found to constitute a standard strategy adopted and promoted by institutions based in Washington DC—such as the US Treasury Department, the International Monetary Fund (IMF), and the World Bank—when dealing with countries that needed to cope with economic crises. The policies concerned macroeconomic stabilization, economic opening with respect to both trade and investment, and the expansion of market forces within the domestic economy. In the past quarter of a century, the topic has been the subject of intense and lively debate, in terms of correct description and acceptable prescription: does the Washington Consensus capture a real historical phenomenon? Does the Washington Consensus ever achieve its goals? Is it to be re-interpreted, despite Williamson’s quite clear definition, as the imposition of neoliberal policies by Washington-based international financial institutions on troubled countries? These are important questions, but the real point of interest here is not the hermeneutical, economic, or normative evaluation of the Washington Consensus. Rather, it is the fact that the very idea, even if it remains only an influential idea, captures a significant aspect of our hyperhistorical, post-Westphalian time. For the Washington Consensus may be seen as the coherent outcome of the United Nations Monetary and Financial Conference, also known as the Bretton Woods Conference (Steil, 2013). This gathering in 1944 of 730 delegates from all forty-four Allied nations at the Mount Washington Hotel in Bretton Woods, New Hampshire, United States, regulated the international monetary and financial order after the conclusion of World War II. It saw the birth of the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (IBRD, together with its concessional lending arm, the International Development Association, it is known as the World Bank), of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT, which will be replaced by the World Trade Organization in 1995), and the International Monetary Fund. In short, Bretton Woods sealed the official emergence of a variety of MASs as supranational or intergovernmental forces involved with the world’s political, social, and economic problems. Thus, Bretton Woods and later on the Washington Consensus highlight the fact that, after World War II, organizations and institutions (not only those in Washington DC) that are not states but rather nongovernmental MASs are openly acknowledged to act as major, influential forces on the political and economic scene internationally, dealing with global problems through global policies. The very fact (no matter whether correct or not) that the Washington Consensus has been accused of being widely mistaken in disregarding local specificities and global differences reinforces the point that a variety of powerful MASs are now the new sources of policies in the globalized information societies.

All this helps to explain why—in a post-Westphalian (emergence of the nation state as the modern, political information agent) and post-Bretton Woods (emergence of non-state MASs as hyperhistorical players in the global economy and politics) world—one of the main challenges we face is how to design the right sort of MASs that could take full advantage of the sociopolitical progress made in modern history, while dealing successfully with the new global challenges that are undermining the best legacy of that very progress in hyperhistory.

Among the many explanations for such a shift from a historical, Westphalian order to a post-Washington Consensus, hyperhistorical predicament in search of a new equilibrium, three are worth highlighting here.

First, power. ICTs “democratize” data and the processing/controlling power over them, in the sense that both now tend to reside and multiply in a multitude of repositories and sources, thus creating, enabling, and empowering a potentially boundless number of non-state agents, from the single individual to associations and groups, from macro-agents, like multinationals, to international, intergovernmental, as well as nongovernmental organizations and supranational institutions. The state is no longer the only, and sometimes not even the main, agent in the political arena that can exercise informational power over other informational agents, in particular over (groups of) citizens. The phenomenon is generating a new tension between power and force, where power is informational, and exercised through the elaboration and dissemination of norms, whereas force is physical, and exercised when power fails to orient the behavior of the relevant agents and norms need to be enforced. The more physical goods and even money become information-dependent, the more the informational power exercised by MASs acquires a significant financial aspect.

Second, geography. ICTs de-territorialize human experience. They have made regional borders porous or, in some cases, entirely irrelevant. They have also created, and are exponentially expanding, regions of the infosphere where an increasing number of agents (not only human, see Floridi, 2013) operate and spend more and more time, the onlife experience. Such regions are intrinsically stateless. This is generating a new tension between geopolitics, which is global and non-territorial, and the nation state, which still defines its identity and political legitimacy in terms of a sovereign territorial unit, as a country.

Third, organization. ICTs fluidify the topology of politics. They do not merely enable but actually promote (through management and empowerment) the agile, temporary, and timely aggregation, disaggregation, and re-aggregation of distributed groups “on demand,” around shared interests, across old, rigid boundaries, represented by social classes, political parties, ethnicity, language barriers, physical barriers, and so forth. This is generating new tensions between the nation state, still understood as a major organizational institution, yet no longer rigid but increasingly morphing into a very flexible MAS itself (I shall return to this point later), and a variety of equally powerful, indeed sometimes even more powerful and politically influential (with respect to the old nation state) non-state organizations, the other MASs on the block. Terrorism, for example, is no longer a problem concerning internal affairs—as some forms of terrorism in the Basque Country, Germany, Italy, or Northern Ireland were—but an international confrontation with a MAS such as Al-Qaeda, the notorious, global, militant Islamist organization.

The debate on direct democracy is thus reshaped. We used to think that it was about how the nation state could reorganize itself internally, by designing rules and managing the means to promote forms of democracy, in which citizens could propose and vote on policy initiatives directly and almost in real time. We thought of forms of direct democracy as complementary options for forms of representative democracy. It was going to be a world of “politics always-on.” The reality is that direct democracy has turned into a mass-media-ted democracy in the ICT sense of new social media. In such digital democracies, MASs (understood as distributed groups, temporary and timely, and aggregated around shared interests) have multiplied and become sources of influence external to the nation state. Citizens vote for their representatives but influence them via opinion polls almost in real time. Consensus-building has become a constant concern based on synchronic information.

Because of the previous three reasons—power, geography, and organization—the unique position of the historical state as the information agent is being undermined from below and overridden from above by the emergence of MASs that have the data, the power (and sometimes even the force, as in the very different cases of the UN, of groups’ cyber threats, or of terrorist attacks), the space, and the organizational flexibility to erode the modern state’s political clout, to appropriate (some of) its authority and, in the long run, make it redundant in contexts where it was once the only or the predominant informational agent. The Greek crisis, which begun in late 2009, and the agents involved in its management, offer a good template: the Greek government and the Greek state had to interact “above” with the EU, the European Central Bank, the IMF, the rating agencies, and so forth, and “below” with the Greek mass media and the people in Syntagma square, the financial markets and international investors, German public opinion, and so forth.

Of course, the historical nation state is not giving up its role without a fight. In many contexts, it is trying to reclaim its primacy as the information superagent governing the political life of the society that it organizes. In some cases, the attempt is blatant. In the UK, the Labour government introduced the first Identity Cards Bill in November 2004. After several intermediary stages, the Identity Cards Act was finally repealed by the Identity Documents Act 2010, on January 21, 2011. The failed plan to introduce compulsory ID in the UK should be read from a modern, Westphalian perspective. In many cases, it is “historical resistance” by stealth, as when an information society—which is characterized by the essential role played by intellectual, intangible assets (knowledge-based economy), information-intensive services (business and property services, finance and insurance), and public sectors (especially education, public administration, and health care)—is largely run by the state, which simply maintains its role of major informational agent no longer just legally, on the basis of its power over legislation and its implementation, but now also economically, on the basis of its power over the majority of information-based jobs. The intrusive presence of so-called “state capitalism” with its SOE (State Owned Enterprises) all over the world, from Brazil, to France, to China, is an obvious symptom of hyperhistorical anachronism.

Similar forms of resistance seem only able to delay the inevitable rise of political MASs. Unfortunately, they may involve huge risks, not only locally, but above all globally. Recall that the two World Wars may be seen as the end of the Westphalian system. Paradoxically, while humanity is moving into a hyperhistorical age, the world is witnessing the rise of China, currently a most “historical” sovereign state, and the decline of the US, a sovereign state that more than any other superpower in the past already had a hyperhistorical and multiagent vocation in its federal organization.

We might be moving from a Washington Consensus to a Beijing Consensus, described by Williamson as consisting of incremental reform, innovation, and experimentation, export-led growth, state capitalism, and authoritarianism. All this is risky, because the anachronistic historicism of some of China’s policies and humanity’s growing hyperhistoricism are heading toward a confrontation. It may not be a conflict, but hyperhistory is a force whose time has come, and while it seems very likely that it will be the Chinese state that will emerge deeply transformed, one can only hope that the inevitable friction will be as painless and peaceful as possible. The financial and social crises that the most advanced information societies are currently undergoing may actually be the very painful but still peaceful price we need pay to adapt to a future post-Washington Consensus order.

The previous conclusion holds true for the historical state in general: in the future, we shall see the political MASs acquire increasing prominence, with the state progressively abandoning its resistance to hyperhistorical changes and evolving into a MAS itself. Good examples are provided by devolution, or the growing trend in making central banks, like the Bank of England or the European Central Bank, independent, public organizations.

The time has come to consider the nature of the political MAS more closely and some of the questions that its emergence is already posing.

The Political MASs

The political MAS is a system constituted by other systems,(4) which, as a single agent, is:

a) teleological: the MAS has a purpose, or goal, which it pursues through its actions;

b) interactive: the MAS and its environment can act upon each other;

c) autonomous: the MAS can change its configurations without direct response to interaction, by performing internal transitions to change its states. This imbues the MAS with some degree of complexity and independence from its environment; and finally,

d) adaptable: the MAS’s interactions can change the rules by which the MAS changes its states. Adaptability ensures that the MAS learns its own mode of operation in a way that depends critically on its experience.

The political MAS becomes intelligent (in the sense of being smart) when it implements features a–d efficiently and effectively, minimizing resources, wastefulness and errors, while maximizing the returns of its actions. The emergence of intelligent, political MASs poses many serious questions, five of which are worth reviewing here, even if only quickly: identity and cohesion, consent, social versus political space, legitimacy, and transparency (the transparent MAS).

Identity and Cohesion

Throughout modernity, the state has dealt with the problem of establishing and maintaining its own identity by working on the equation between State = Nation, often through the legal means of Citizenship and the narrative rhetoric of Space (the Mother/Father Land) and Time (Story in the sense of traditions, recurrent celebrations of past nation-building events, etc.). Consider, for example, the invention of mandatory military service during the French Revolution, its increasing popularity in modern history, but then the decreasing number of sovereign states that still impose it nowadays. Conscription transformed the right to wage war from an eminently economic problem—Florentine bankers financed the English kings during the Hundred Years War (1337–1453), for example—into also a legal problem: the right of the state to send its citizens to die on its behalf, thus making human life the penultimate value, available for the ultimate sacrifice, in the name of patriotism. “For King and Country”: it is a sign of modern anachronism that, in moments of crisis, sovereign states still give in to the temptation of fuelling nationalism about meaningless, geographical spots, often some small islands unworthy of any human loss, from the Falkland Islands or Islas Malvinas to the Senkaku or Diaoyu Islands.

The equation between State, Nation, Citizenship and Land/Story had the further advantage of providing an answer to a second problem, that of cohesion, for it answered not just the question of who or what the state is, but also the question of who or what belongs to the state and hence may be subject to its norms, policies, and actions. New political MASs cannot rely on the same solution. Indeed, they face the further problem of having to deal with the decoupling of their political identity and cohesion. The political identity of a MAS may be very strong and yet unrelated to its temporary and rather loose cohesion, as is the case with the Tea Party movement in the US. Both identity and cohesion of a political MAS may be rather weak, as in the international Occupy movement. Or one may recognize a strong cohesion and yet an unclear or weak political identity, as with the population of tweeting individuals and their role during the Arab Spring. Both identity and cohesion of a political MAS are established and maintained through information sharing. The Land is virtualized into the region of the infosphere in which the MAS operates. So Memory (retrievable recordings) and Coherence (reliable updates) of the information flow enable a political MAS to claim some identity and some cohesion, and therefore offer a sense of belonging. But it is, above all, the fact that the boundaries between the online and offline are disappearing, the appearance of the onlife experience, and hence the fact that the virtual infosphere can affect politically the physical space, that reinforces the sense of the political MAS as a real agent. If Anonymous had only a virtual existence, its identity and cohesion would be much less strong. Deeds provide a vital counterpart to the virtual information flow to guarantee cohesion. An ontology of interactions replaces an ontology of entities, or, with a word play, ings (as in interact-ing, process-ing, network-ing, do-ing, be-ing, etc.) replace things.

Consent

A significant consequence of the breaking up of the equation “political MAS = Nation State = Citizenship = Land = Story” and of the decoupling of identity and cohesion in a political MAS is that the age-old theoretical problem of how consent to be governed by a political authority arises is being turned on its head. In the historical framework of social contract theory, the presumed default position is that of a legal opt-out: there is some kind of (to be specified) a priori, original consent, allegedly given (for a variety of reasons) by any individual subject to the political state, to be governed by the latter and its laws. The problem is to understand how such consent is given and what happens when an agent, especially a citizen, opts out of it (the out-law). In the hyperhistorical framework, the expected default position is that of a social opt-in, which is exercised whenever the agent subjects itself to the political MAS conditionally, for a specific purpose. Oversimplifying, we are moving from being part of the political consensus to taking part in it, and such part-taking is increasingly “just in time,” “on demand,” “goal-oriented,” and anything but permanent or long-term, and stable. If doing politics looks increasingly like doing business it is because, in both cases, the interlocutor, the citizen-customer needs to be convinced every time anew. Loyal membership is not the default position, and needs to be built and renewed around political and commercial products alike. Gathering consent around specific political issues becomes a continuous process of (re)engagement. It is not a question of political attention span—the generic complaint that “new generations” cannot pay sustained attention to political problems anymore is unfounded; they are, after all, the generations that binge-watch TV—but of motivating interest again and again, without running into semantic inflation (one more crisis, one more emergency, one more revolution, one more…) and political fatigue (how many times do we need to intervene urgently?). The problem is therefore to understand what may motivate repeatedly or indeed force agents (again, not just individual human beings, but all kinds of agents) to give such consent and become engaged, and what happens when such agents, unengaged by default (note, not disengaged, for disengagement presupposes a previous state of engagement), prefer to stay away from the activities of the political MAS, inhabiting a social sphere of civil but apolitical “nonimity” (lack of anonymity). Failing to grasp the previous transformation from historical opt-out to hyperhistorical opt-in means being less likely to understand the apparent inconsistency between the disenchantment of individuals with politics and the popularity of global movements, international mobilizations, activism, voluntarism, and other social forces with huge political implications. What is moribund is not politics tout court, but historical politics, that based on parties, classes, fixed social roles, and the nation state, which sought political legitimacy only once and spent it until revoked. The inching toward the so-called center by parties in liberal democracies around the world, as well as the “Get out the vote” strategies (GOTV is a term used to describe the mobilization of voters as supporters to ensure that those who can do vote) are evidence that engagement needs to be constantly renewed and expanded in order to win an election. Party (as well as Union) membership is a modern feature that is likely to become increasingly less common.

Social vs. Political Space

Understanding the previous inversion of default positions means being faced by a further problem. Oversimplifying once more, in prehistory, the social and the political spaces overlap because, in a stateless society, there is no real difference between social and political relations and hence interactions. In history, the state seeks to maintain such coextensiveness by occupying, as an informational MAS, all the social space politically, thus establishing the primacy of the political over the social. This trend, if unchecked and unbalanced, risks leading to totalitarianisms (e.g., the Italy of Mussolini), or at least broken democracies (e.g., the Italy of Berlusconi). We have seen earlier that such a coextensiveness and its control may be based on normative or economic strategies, through the exercise of power, force, and rule-making. In hyperhistory, the social space is the original, default space from which agents may move to (consent to) join the political space. It is not accidental that concepts such as civil society (in the post-Hegelian sense of nonpolitical society), public sphere (also in a non-Habermasian sense), and community become increasingly important the more we move into a hyperhistorical context. The problem is to understand such social space where agents of various kinds are supposed to be interacting and which gives rise to the political MAS.

Each agent, as described earlier, has some degrees of freedom. By this I do not mean liberty, autonomy or self-determination, but rather, in the robotic, more humble sense, some capacities or abilities, supported by the relevant resources, to engage in specific actions for a specific purpose. To use an elementary example, a coffee machine has only one degree of freedom: it can make coffee, once the right ingredients and energy are supplied. The sum of an agent’s degrees of freedom is its “agency.” When the agent is alone, there is of course only agency, but no social let alone political space. Imagine Robinson Crusoe on his “Island of Despair.” However, as soon as there is another agent (Friday on the “Island of Despair”), or indeed a group of agents (the native cannibals, the shipwrecked Spaniards, the English mutineers), agency acquires the further value of multiagent (i.e., social) interaction: practices and then rules for coordination and constraint of the agents’ degrees of freedom become essential, initially for the well-being of the agents constituting the MAS, and then for the well-being of the MAS itself. Note the shift in the level of analysis: once the social space arises, we begin to consider the group as a group—for example, as a family, or a community, or as a society—and the actions of the individual agents constituting it become elements that lead to the MAS’s newly established degrees of freedom, or agency. The previous simple example may still help. Consider now a coffee machine and a timer: separately, they are two agents with different agency, but if they are properly joined and coordinated into a MAS, then the issuing agent has the new agency to make coffee at a set time. It is now the MAS that has a more complex capacity, and that may or may not work properly.

A social space is thus the totality of degrees of freedom of the inhabiting agents one wishes to take into consideration. In history, such consideration—which is really just another level of analysis—was largely determined physically and geographically, in terms of presence in a territory, and hence by a variety of forms of neighborhood. In the previous example, all the agents interacting with Robinson Crusoe are taken into consideration because of their relations (interactive presence in terms of their degree of freedom) to the same “Island of Despair.” We saw that ICTs have changed all this. In hyperhistory, where to draw the line to include, or indeed exclude, the relevant agents whose degrees of freedom constitute the social space has become increasingly a matter of at least implicit choice, when not of explicit decision. The result is that the phenomenon of distributed morality, encompassing that of distributed responsibility, is becoming more and more common. In either case, history or hyperhistory, what counts as a social space may be a political move. Globalization is a de-territorialization in this political sense.

If we now turn to the political space in which the new MASs operate, it would be a mistake to consider it a separate space, over and above the social one: both are determined by the same totality of the agents’ degrees of freedom. The political space emerges when the complexity of the social space—understood in terms of number and kinds of interactions and of agents involved, and of degree of dynamic reconfiguring of both agents and interactions—requires the prevention or resolution of potential divergences and the coordination or collaboration about potential convergences. Both are crucial. And in each case more information is required, in terms of representation and deliberation about a complex multitude of degrees of freedom. The result is that the social space becomes politicized through its informatization.

Legitimacy

It is when the agents in the social space agree to agree on how to deal with their divergences (conflicts) and convergences that the social space acquires the political dimension to which we are so used. Yet two potential mistakes await us here.

The first, call it Hobbesian, is to consider politics merely as the prevention of war by other means, to invert the famous phrase by Carl von Clausewitz, according to which “war is the continuation of politics by other means.” This is not the case, because even a complex society of angels (Homo hominis agnus) would still require rules in order to further its harmony. Convergences too need politics. Out of metaphor, politics is not just about conflicts due to the agents’ exercises of their degree of freedom when pursuing their goals. It is also, or at least it should be, above all, the furthering of coordination and collaboration of degrees of freedom by means other than coercion and violence.

The second, and one may call this potential mistake Rousseauian, is that it may seem that the political space is then just that part of the social space organized by law. In this case, the mistake is subtler. We usually associate the political space with the rules or laws that regulate it but the latter are not constitutive, by themselves, of the political space. Compare two cases in which rules determine a game. In chess, the rules do not merely constrain the game, they are the game because they do not supervene on a previous activity: rather, they are the necessary and sufficient conditions that determine all and only the moves that can be legally made. In football, however, the rules are supervening constraints because the agents enjoy a previous and basic degree of freedom, consisting in their capacity to kick a ball with the foot in order to score a goal, which the rules are supposed to regulate. Whereas it is physically possible, but makes no sense, to place two pawns on the same square of a chessboard, nothing impeded Maradona from scoring an infamous goal by using his hand in the Argentina vs. England football match (1986 FIFA World Cup), and that to be allowed by a referee who did not see the infringement.

Once we avoid the two previous mistakes, it is easier to see that the political space is that area of the social space constrained by the agreement to agree on resolution of divergences and coordination of convergences. This leads to a further consideration, concerning the transparent MAS, especially when, in this transition time, the MAS in question is still the state.

The Transparent MAS

There are two senses in which the MAS can be transparent. Unsurprisingly, both come from ICTs and Computer Science (Turilli & Floridi, 2009), one more case in which the information revolution is changing our mental frameworks.

On the one hand, the MAS (think of the nation state, and also corporate agents, multinationals, or supranational institutions, etc.) can be transparent in the sense that it moves from being a black box to being a white box. Other agents (citizens, when the MAS is the state) not only can see inputs and outputs—for example, levels of tax revenue and public expenditure—they can also monitor how (in our running example, the state as) a MAS works internally. This is not a novelty at all. It was a principle already popularized in the nineteenth century. However, it has become a renewed feature of contemporary politics due to the possibilities opened up by ICTs. This kind of transparency is also known as Open Government.

On the other hand, and this is the more innovative sense that I wish to stress here, the MAS can be transparent in the same sense in which a technology (e.g., an interface) is: invisible, not because it is not there, but because it delivers its services so efficiently, effectively, and reliably that its presence is imperceptible. When something works at its best, behind the scenes as it were, to make sure that we can operate as efficiently and as smoothly as possible, then we have a transparent system. When the MAS in question is the state, this second sense of transparency should not be seen as a surreptitious way of introducing, with a different terminology, the concept of “Small State” or “Small Governance.” On the contrary, in this second sense, the MAS (the state) is as transparent and as vital as the oxygen that we breathe. It strives to be the ideal butler.(5) There is no standard terminology for this kind of transparent MAS that becomes perceivable only when it is absent. Perhaps one may speak of Gentle Government. It seems that MASs can increasingly support the right sort of ethical infrastructure (more on this later) the more transparently, that is, openly and gently, they play the negotiating game through which they take care of the res publica. When this negotiating game fails, the possible outcome is an increasingly violent conflict among the parties involved. It is a tragic possibility that ICTs have seriously reconfigured.

All this is not to say that opacity does not have its virtues. Care should be exercised, lest the sociopolitical discourse is reduced to the nuances of higher quantity, quality, intelligibility, and usability of information and ICTs. The more the better is not the only, nor always the best, rule of thumb. For the withdrawal of information can often make a positive and significant difference. We already encountered Montesquieu’s division of the state’s political powers. Each of them may be carefully opaque in the right way to the other two. For one may need to lack (or intentionally preclude oneself from accessing) some information in order to achieve desirable goals, such as protecting anonymity, enhancing fair treatment, or implementing unbiased evaluation. Famously, in Rawls (1999), the “veil of ignorance” exploits precisely this aspect of information, in order to develop an impartial approach to justice. Being informed is not always a blessing and might even be dangerous or wrong, distracting or crippling. The point is that opacity cannot be assumed to be a good feature in a political system unless it is adopted explicitly and consciously, by showing that it is not a mere bug.

Infraethics

Part of the ethical efforts engendered by our hyperhistorical condition concerns the design of environments that can facilitate MASs’ ethical choices, actions, or process. This is not the same as ethics by design. It is rather pro-ethical design, as I hope will become clearer in the following pages. Both are liberal, but the former may be mildly paternalistic, insofar as it privileges the facilitation of the right kind of choices, actions, process or interactions on behalf of the agents involved, whereas the latter does not have to be, insofar as it privileges the facilitation of reflection by the agents involved on their choices, actions, or process(6). For example, the former may let people opt out of the default preference according to which, by obtaining a driving licence, one is also willing to be an organ donor. The latter may not allow one to obtain a driving license unless one has decided whether one wishes to be an organ donor. In this section, I shall call environments that can facilitate ethical choices, actions, or process, the ethical infrastructure, or infraethics. I shall call the reader’s attention to the problem of how to design the right sort of infraethics for the emerging MASs. In different contexts or cases, the design of a liberal infraethics may be more or less paternalistic. My argument is that it should be as little paternalistic as the circumstances permit, although no less.

It is a sign of the times that, when politicians speak of infrastructure nowadays, they often have in mind ICTs. They are not wrong. From business fortunes to conflicts, what makes contemporary societies work depends increasingly on bits rather than atoms. We already saw all this. What is less obvious, and philosophically more interesting, is that ICTs seem to have unveiled a new sort of equation.

Consider the unprecedented emphasis that ICTs have placed on crucial phenomena such as trust, privacy, transparency, freedom of expression, openness, intellectual property rights, loyalty, respect, reliability, reputation, rule of law, and so forth. These are probably better understood in terms of an infrastructure that is there to facilitate or hinder (reflection upon) the im/moral behavior of the agents involved. Thus, by placing our informational interactions at the center of our lives, ICTs seem to have uncovered something that, of course, has always been there, but less visibly so: the fact that the moral behavior of a society of agents is also a matter of “ethical infrastructure” or simply infraethics. An important aspect of our moral lives has escaped much of our attention and indeed many concepts and related phenomena have been mistakenly treated as if they were only ethical, when in fact they are probably mostly infraethical. To use a term from the philosophy of technology, they have a dual-use nature: they can be morally good, but also morally evil (more on this presently). The new equation indicates that, in the same way that business and administration systems, in an economically mature society, increasingly require infrastructures (transport, communication, services, etc.), so too, moral interactions increasingly require an infraethics, in an informationally mature society.

The idea of an infraethics is simple, but can be misleading. The previous equation helps to clarify it. When economists and political scientists speak of a “failed state,” they may refer to the failure of a state-as-a-structure to fulfill its basic roles, such as exercising control over its borders, collecting taxes, enforcing laws, administering justice, providing schooling, and so forth. In other words, the state fails to provide public (e.g., defense and police) and merit (e.g., health care) goods. Or (too often an inclusive and intertwined or) they may refer to the collapse of a state-as-an-infrastructure or environment, which makes possible and fosters the right sort of social interactions. This means that they may be referring to the collapse of a substratum of default expectations about economic, political, and social conditions, such as the rule of law, respect for civil rights, a sense of political community, civilized dialogue among differently minded people, ways to reach peaceful resolutions of ethnic, religious, or cultural tensions, and so forth. All these expectations, attitudes, practices, in short such an implicit “sociopolitical infrastructure,” which one may take for granted, provides a vital ingredient for the success of any complex society. It plays a crucial role in human interactions, comparable to the one that we are now accustomed to attributing to physical infrastructures in economics.

Thus, infraethics should not be understood in terms of Marxist theory, as if it were a mere update of the old “base and superstructure” idea, because the elements in question are entirely different: we are dealing with moral actions and not-yet-moral facilitators of such moral actions. Nor should it be understood in terms of a kind of second-order normative discourse on ethics, because it is the not-yet-ethical framework of implicit expectations, attitudes, and practices that can facilitate and promote moral decisions and actions. At the same time, it would also be wrong to think that an infraethics is morally neutral. Rather, it has a dual-use nature, as I anticipated earlier: it can both facilitate and hinder morally good as well as evil actions, and do this in different degrees. At its best, it is the grease that lubricates the moral mechanism. This is more likely to happen whenever having a “dual-use” nature does not mean that each use is equally likely, that is, that the infraethics in question is still not neutral, nor merely positive, but does have a bias to deliver more good than evil. If this is confusing, think of a the dual-use nature not in terms of an equilibrium, like an ideal coin that can deliver both heads and tail, but in terms of a co-presence of two alternative outcomes, one of which is more likely than the other, like in a biased coin more likely to turn heads than tails. When an infraethics has a “biased dual-use” nature, it is easy to mistake the infraethical for the ethical, since whatever helps goodness to flourish or evil to take root partakes of their nature.

Any successful complex society, be this the City of Man or the City of God, relies on an implicit infraethics. This is dangerous, because the increasing importance of an infraethics may lead to the following risk: that the legitimization of the ethical ground is based on the “value” of the infraethics that is supposed to support it. Supporting is mistaken for grounding, and may even aspire to the role of legitimizing, leading to what Lyotard criticized as mere “performativity” of the system, independently of the actual values cherished and pursued. Infraethics is the vital syntax of a society, but it is not its semantics, to use a distinction popular in artificial intelligence. It is about the structural form, not the meaningful contents.

We saw earlier that even a society in which the entire population consisted of angels, that is, perfect moral agents, still needs norms for collaboration. Theoretically, that is, when one assumes that morally good values and the infraethics that promotes them may be kept separate (an abstraction that never occurs in reality but that facilitates our analysis), a society may exist in which the entire population consisted of Nazi fanatics who could rely on high levels of trust, respect, reliability, loyalty, privacy, transparency, and even freedom of expression, openness, and fair competition. Clearly, what we want is not just the successful mechanism provided by the right infraethics, but also the coherent combination between it and morally good values, such as civil rights. This is why a balance between security and privacy, for example, is so difficult to achieve, unless we clarify first whether we are dealing with a tension within ethics (security and privacy as a moral rights), within infraethics (both are understood as not-yet-ethical facilitators), or between infraethics (security) and ethics (privacy), as I suspect. To rely on another analogy: the best pipes (infraethics) may improve the flow but do not improve the quality of the water (ethics), and water of the highest quality is wasted if the pipes are rusty or leaky. So creating the right sort of infraethics and maintaining it is one of the crucial challenges of our time, because an infraethics is not morally good in itself, but it is what is most likely to yield moral goodness if properly designed and combined with the right moral values. The right sort of infraethics should be there to support the right sort of axiology (theory of value). It is certainly a constitutive part of the problem concerning the design of the right MASs.

The more complex a society becomes, the more important and hence salient the role of a well-designed infraethics is, and yet this is exactly what we seem to be missing. Consider the recent Anti-Counterfeiting Trade Agreement (ACTA), a multinational treaty concerning the international standards for intellectual property rights. By focusing on the enforcement of IPR (intellectual property rights), supporters of ACTA completely failed to perceive that it would have undermined the very infraethics that they hoped to foster, namely one promoting some of the best and most successful aspects of our information society. It would have promoted the structural inhibition of some of the most important individuals’ positive liberties and their ability to participate in the information society, thus fulfilling their own potential as informational organisms. For lack of a better word, ACTA would have promoted a form of informism, comparable to other forms of social agency’s inhibition such as classism, racism, and sexism. Sometimes a defense of liberalism may be inadvertently illiberal. If we want to do better, we need to grasp that issues such as IPR are part of the new infraethics for the information society, that their protection needs to find its carefully balanced place within a complex legal and ethical infrastructure that is already in place and constantly evolving, and that such a system must be put at the service of the right values and moral behaviors. This means finding a compromise, at the level of a liberal infraethics, between those who see new legislation (such as ACTA) as a simple fulfillment of existing ethical and legal obligations (in this case from trade agreements), and those who see it as a fundamental erosion of existing ethical and legal civil liberties.

In hyperhistorical societies, any regulation affecting how people deal with information is now bound to influence the whole infosphere and onlife habitat within which they live. So enforcing rights (such as IPR) becomes an environmental problem. This does not mean that any legislation is necessarily negative. The lesson here is one about complexity: since rights such as IPR are part of our infraethics and affect our whole environment understood as the infosphere, the intended and unintended consequences of their enforcement are widespread, interrelated, and far-reaching. These consequences need to be carefully considered, because mistakes will generate huge problems that will have cascading costs for future generations, both ethically and economically. The best way to deal with “known unknowns” or unintended consequences is to be careful, stay alert, monitor the development of the actions undertaken, and be ready to revise one’s decision and strategy quickly, as soon as the wrong sort of effects start appearing. Festina lente, “more haste, less speed” as the classic adage suggests. There is no perfect legislation but only legislation that can be perfected more or less easily. Good agreements about how to shape our infraethics should include clauses about their timely update.

Finally, it is a mistake to think that we are like outsiders ruling over an environment different from the one we inhabit. Legal documents (such as ACTA) emerge from within the infosphere that they affect. We are building, restoring, and refurbishing the house from inside, or one may say that we are repairing the raft while navigating on it, to use the metaphor introduced in the Preface. Precisely because the whole problem of respect, infringement, and enforcement of rights (such as IPR) is an infraethical and environmental problem for advanced information societies, the best thing we could do, in order to devise the right solution, is to apply to the process itself the very infraethical framework and ethical values that we would like to see promoted by it. This means that the infosphere should regulate itself from within, not from an impossible without.

Conclusion: the Last of the Historical Generations?

Six thousand years ago, a generation of humans witnessed the invention of writing and the emergence of the conditions of possibility of cities, kingdoms, empires, and nation states. This is not accidental. Prehistoric societies are both ICT-less and stateless. The state is a typical historical phenomenon. It emerges when human groups stop living a hand-to-mouth existence in small communities and begin to live a mouth-to-hand one, in which large communities become political societies, with division of labor and specialized roles, organized under some form of government, which manages resources through the control of ICTs, including that very special kind of information called “money.” From taxes to legislation, from the administration of justice to military force, from census to social infrastructure, the state was for a long time the ultimate information agent and so I suggested that history, and especially modernity, is the age of the state.

Almost halfway between the beginning of history and now, Plato was still trying to make sense of both radical changes: the encoding of memories through written symbols and the symbiotic interactions between individuals and polis-state. In fifty years, our grandchildren may look at us as the last of the historical, state-organized generations, not so differently from the way we look at the Amazonian tribes mentioned at the beginning of this chapter, as the last of the prehistorical, stateless societies. It may take a long while before we come to understand in full such transformations. And this is a problem, because we do not have another six millennia in front of us. We cannot wait for another Plato in a few millennia. We are playing an environmental gambit with ICTs, and we have only a short time to win the game, for the future of our planet is at stake. We better act now.

Notes

1. According to data about life expectancy at birth for the world and major development groups, 1950–2050. Source: Population Division of the Department of Economic and Social Affairs of the United Nations Secretariat (2005). World Population Prospects: The 2004 Revision Highlights. New York: United Nations, available online.

2. According to data about poverty in the word, defined as the number and share of people living below $1.25 a day (at 2005 prices) in 2005–08. Source: World Bank, and The Economist, 29 February, 2012, available online.

3. Floridi & Taddeo (forthcoming). Clarke & Knake (2010) approach the problems of cyberwar and cybersecurity from a political perspective that would still qualify as “historical” within this chapter, but it is very helpful.

4. For a more detailed analysis see Floridi, 2011.

5. On good governance and the rules of the political, global game, see Brown & Marsden, 2013.

6. I have sought to develop an information ethics in Floridi, 2013. For a more introductory text see Floridi, 2010.

Select Bibliography

— Brown, I., & Marsden, C. T. (2013). Regulating Code: Good Governance and Better Regulation in the Information Age. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

— Clarke, R. A., & Knake, R. K. (2010). Cyber War: The Next Threat to National Security and What to Do About It. New York: Ecco.

— Floridi, L. (2011). The Philosophy of Information. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

— Floridi, L. (2013). The Ethics of Information. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

— Floridi, L. (ed.). (2010). The Cambridge Handbook of Information and Computer Ethics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

— Floridi, L., & Taddeo, M. (eds.). (2014). The Ethics of Information Warfare. New York: Springer.

— Linklater, A. (1998). The Transformation of Political Community: Ethical Foundations of the Post-Westphalian Era. Oxford: Polity.

— Rawls, J. (1999). A Theory of Justice (rev. ed.). Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

— Steil, B. (2013). The Battle of Bretton Woods. John Maynard Keynes, Harry Dexter White, and the Making of a New World Order. New Jersey: Princeton University Press.

— Turilli, M., & Floridi, L. (2009). “The ethics of information transparency.” Ethics and Information Technology, 11(2), 105–112.

Comments on this publication