It is tempting to think that the subject of this work falls outside the capacities, or even the interest, of an artist—in my case, a composer, which only makes things worse, given the elusive nature of music as a language.

And that may even be the case. It all depends on the meaning we assign to the term “knowledge.”

I’ll avoid the useless trap of enumerating the avatars that the verb “to know” may have assumed over the course of its history, limiting myself to the most immediate dictionary definitions. The María Moliner dictionary of the Spanish language (second edition, 1998) offers the following primary definition of “knowledge”: “The act of knowing.” This is followed by, “The effect of knowing or the presence in the mind of ideas about something… things one knows with certainty, art… the capacity of knowing what is or is not convenient and of behaving in accordance with that knowledge… prudence, sensibility…” and so on, forming a wise and considerable list.

I believe the question we are being asked, at least as I understand it, is not so broad. If I have understood it correctly, we are being asked whether our “knowledge”—“act of knowing,” “presence in the mind of ideas about something”—of our field of activity—in my case, music composition—could or should have limits, either because of the incapacity of our sensory organs—and their man-made aids—or because of the risks that “knowledge” might entail if used in an irresponsible or harmful manner.

Off the cuff, I can only answer in one way: music doesn’t involve any knowledge of that sort. It is neither a question of incapacity nor of risk. Quite simply, music occupies a different place, as human as that of science—and maybe even more necessary to humanity’s inner equilibrium—but it responds to different needs or, if you prefer, fulfills different functions.

In the interest of greater understanding, allow me to formulate this question from a composer’s point of view: something like “the frontiers of artistic expression.” It would be interesting to pose that question to my admired colleagues. I am certain that I, at least, would learn much from doing so. Before continuing, I would like to clarify something. There are other “frontiers,” which I will mention in the interests of disclosure, but will not actually discuss. Music involves ordering—or disordering—sounds and silences in time. We already know there are divergent opinions about this, but I will not enter that debate. There is also the “frontier” of music’s meaning in present-day society. After all, music is not merchandise, even though composers and performers try to make a living from it. But some musicians are born to be merchandise. Even worse, there is excellent music that has been used in such a way that it has become merchandise. But I will not enter that jungle, either—Pascal Quignard quite rightly speaks of La haine de la Musique (“Hate of Music”)—for I am not a sociologist. Let us return to the matter at hand.

If anything is clear after consulting a definition of “knowledge” it is that it “lies”—so to speak—in the conscious, that is, in the supposedly rational and conscious world. To many people, “unconscious” knowledge may seem little more than a play on words, a contradiction and almost an oxymoron.

And yet, given what is involved in carrying out certain practices that imply the acquisition of knowledge, this may not be so clear-cut. Learning a language, for example, involves two clearly differentiated phases. The first is a conscious, constant, and deliberate labor of memorization. The second could be called assimilation, when what has been learned with conscious effort enters an individual’s unconscious—such are the benefits of practice. When that happens, language no longer requires any deliberation. It simply comes out, for better or worse, with the spontaneity of what is supposedly known and assimilated.

Music, like any other language, is learned that way in its most elemental phase. We could even say, without exaggerating, that everything is learned that way, when it does not reach beyond that level of practical knowledge.

In that phase, music is a craft like any other—and I use the term “craft” it its most noble sense, because it is, indeed, noble. As such, its knowledge has frontiers defined by efficiency. They reach from mere sufficiency to levels of prodigy.

But behind its “craft,” music holds many surprises, other kinds of knowledge that are not so much learned as invented. A trained composer—even before he is trained—finds himself facing the door of the enigma that led him to choose that profession. He is, in effect, face-to-face with his craft. He has learned many things. Some he considers useless, others he would rather forget—at least that is what he thinks—and still others he keeps just in case… But now, he must find his voice, and that, by its very definition, calls for “another” craft that has yet to be defined. Its definition—as in Kafka’s short story, “The Trial”—is absolutely personal: only he can define it. Before, he had to assimilate pre-established teachings without objecting, but now he must be judge and jury; he must seek, find, use, and evaluate. The possible “knowledge” such work can offer him will not be a code of inherited rules; it will be one derived from his expressive objectives. If, as the years pass, he meets those objectives, they will become the heritage of a more-or-less significant collective: a profound and always faithful, though partial, reflection—there has yet to be one that spans all of humanity—of what it meant to be a man at a specific time and place (I will return to this idea, below).

With what I have already said, I believe we can accept the thesis that music is not about transmitting solid, invariable or even evolving “knowledge” about anything. It shares this with the other arts and also, I suspect, with the so-called “sciences of man,” although the latter do so in a different way and for different reasons. In music, and in art in general, the experience produced by this “knowledge beyond craft,” is emotional, even for the scholar, not to mention composer, performer, and audience. A French expression which, out of decency, I will refrain from translating—it was one of Stravinsky’s catch phrases—is crudely illustrative: “ça ne me fait pas bander.”

Knowledge based on emotion is always suspect for a scientist—even when he, himself, is moved by it—and so it must be. Scientific knowledge is transmitted through words and formulas, but is the word the only medium for communicating or transmitting knowledge? As a composer, it is not my job to address the questions of “word and thing,” “word and way of knowing,” and so on, so I will only say that excessive verbalization destroys entire areas of human expression, and music is undoubtedly an eloquent demonstration of this.

Earlier, I insinuated that artistic creation—and music as well, though there are hardly any remains of its earliest manifestations—began incommensurably earlier than science. Let this embarrassingly obvious observation serve, here, to emphasize that pre-scientific forms of “knowledge” were the only ones possessed by human beings for a very, very long time. Of course that is not a justification, but then, I am not trying to justify anything. I simply seek to point out realities of our human nature that it would not be proper to forget, let alone combat. Here, there are certainly “frontiers” but they are not those of a musician.

As I understand it, the type of “knowing”—perhaps a better term than “knowledge” when dealing with art—offered by music moves between the conscious and the unconscious: a constant back-and-forth that enriches both spheres. Perhaps that is one of its greatest charms, or even the reason why it is so absolutely necessary.

Let us, then, accept the possibility of a “knowing” of these characteristics, even if only hypothetically. Let us accept—and this is the true leap of faith—that it can be spoken and written about.

The questions that arise multiply like rabbits. How can we speak about an art that does not employ words, except when discussing its technique or craft? How can we calibrate or measure the emotion it produces? Is it possible to conceive of a repertoire of expressive means that can be used to deliberately provoke certain states of mind? And if such means exist, can they be cataloged? What can be done with the countless forms of expression that have been accumulated by different cultures and epochs? Are they interchangeable or, instead, mutually incomprehensible? How can a musical language be made collective? Would such a thing be desirable? What should we think of the old adage “music is a universal language?” And so on and so on… It is impossible to conceive of answering them in detail, and offering an overall answer is the same as avoiding them altogether, or simply lying.

As for me, I can only jot down a few comments and, if Erato—or Euterpe if you prefer, but not Melpomene, please!—inspires me, I can opine with prudence and discretion on this confusing labyrinth.

The aspiration of defining a repertory of musical means capable of provoking precise states of mind is as ancient as the first known documents. This would seem to indicate that it is actually as old as music itself, with or without documentation. It may not be entirely useless to glance at some chapters of its history—particularly the oldest ones—from the standpoint of what materials they employed. That excursion will reveal the successive “frontiers” that musical “knowledge” has experienced. I confess a certain reluctance to present this bird’s eye view of music—no less—in what may be too personal a manner. On the other hand, much of what I will say is common knowledge—or so I believe. A thousand pardons, then, for doing so, but I see no other way to speak clearly, and with some meaning—usefully, in other words—about the delicate subject I am attempting to address.

The first documents—Hindu, Greek, Chinese, Tibetan, and many, many, more—are abundant. Almost all of them aspire to the same thing: either to awaken emotional states in the listener, or to serve as prayer. The musical means employed are highly varied.

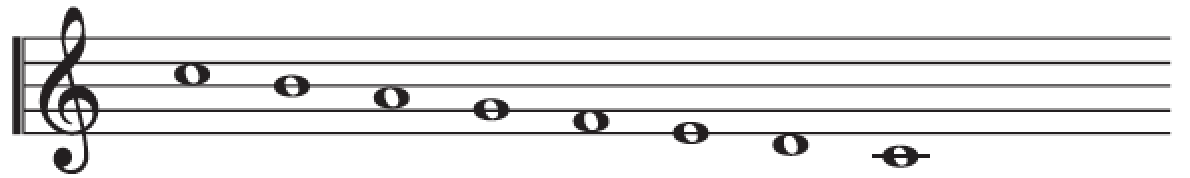

The Greeks were convinced of the expressive value, and most of all, the ethical value of Music: valor, cowardice, faithfulness or softness could all be provoked, increased or diminished by it—one need only read the classics. There are abundant technical texts. Perhaps the most ample of these is by Aristoxenus of Tarentum (4th century BC), and I will limit myself to him here. The central musical idea was “monody.” It consisted of notes based on the natural resonance of bodies: natural intervals of the fifth and its inversion. Monody was accompanied by the octave and, beginning in the fourth century, fourths and fifths as well, which corresponds to his concept of “scale” organized in tetrachords, that is, four notes together. The outermost notes of a tetrachord are “fixed notes,” and the ones in between vary according to which kind of tetrachord it is: diatonic, chromatic, or enharmonic. There is no diapason—in other words, no absolute pitch, for that is exclusively Western and arrived much later on. The Greek word, diapason designates two successive tetrachords—that is, an octave. The notes that make up this double tetrachord already bear their name, indicating their position in the tuning of the lyre. There are seven types of octave, each with its name and mood. Those names are almost identical to the ecclesiastical modes of Christianity, but the actual scales do not correspond. For example the Greek Lydian mode is:

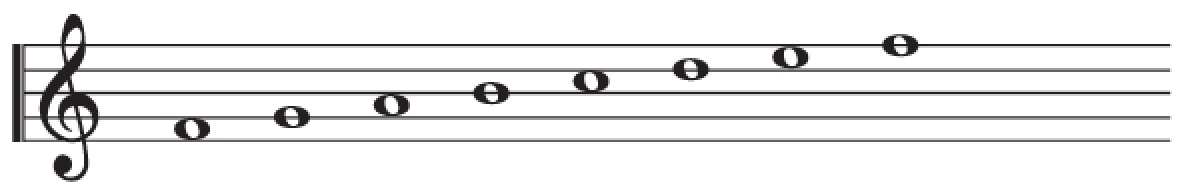

(from C to C), while the ecclesiastical Lydian is:

(from F to F).

All of this theory—which is highly detailed and would be bothersome to completely explain here—does not seem to correspond very well with practice, which was steeped in an oral tradition subject—as they all are—to constant and not especially foreseeable changes. This has undoubtedly kept us from knowing how the music of ancient Greece “really” sounded.

In the secular music of northern India, which is also very rich in theory, ragas (modes, more or less) and talas (rhythmic structures) are meticulously precise: the time of day or night, the season, mood, and so on. The material of ragas, that is, their pitches or intervals, is extracted from the 22 pitch-classes that make up the complete scale, of which the corresponding raga almost always uses seven. A raga needs a constant reference point in order to achieve the desired effect. Therefore, there is always an instrument—the tampura or shruti—whose function is similar to what would be called a “pedal” in Europe, that is, a continuous note. Naturally, there are numerous ragas: there is the raga (father), and the ragini (mother), which are mated to produce innumerable descendents: putra (sons) and putri (daughters). The tala use two tablas—hand and finger drums—and are equally subject to rigorous codification. Once the apprentice has mastered this complex mechanism, he is free to use it with imagination—Hindu compositional forms stimulate the capacity to improvise. The music of northern India surpasses that of ancient Greece in its effects: it can cure (or cause) illnesses, stop (or start) storms, and so on.

Vedic psalmody, the most archaic religious music from Northern India, and possibly the oldest known musical documentation, may be one of the most intricate manners imaginable for establishing contact with the divine. The Brahman’s voice plays with the text in a thousand ways, all codified: the order of the phrases and syllables, changing accentuation, subtle changes of pitch, and so on. The result is incomprehensible to the uninitiated. Perhaps that is deliberate: these songs of praise—not prayers—must be accessible only to the superior caste.

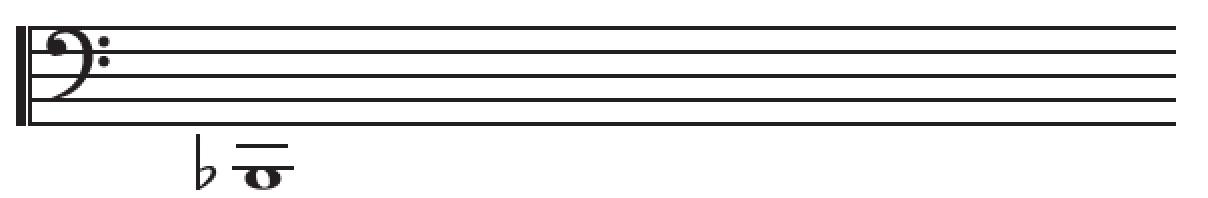

To keep this introduction from being too long, I will only allude to the vocal techniques of Tibetan religious chanting—they chant on texts from Tantric Buddhism—which seek the same goal, that is, making the sacred text incomprehensible by projecting the male voice into an unusual register. This is done with very precise techniques and serves to keep “knowledge” considered “dangerous” out of the hands of the uninitiated.

Lower limit of the voice, around:

Without generalizing then, it is possible to say that what is known about ancient musical cultures indicates a belief that music has an unquestionable capacity to generate a great variety of emotional states that are determinable and determined, as well as the capacity to contact the divine (both can go together). It also shows that those powers and capacities have taken innumerable forms and have, in turn, constituted a first approach to discovering and using the nature of sound as a physical phenomenon. Behind all this there is a clear and shared necessity to use sound as an expressive vehicle, a guide or compass in a spiritualized universe. This necessity is as urgent as the need for food, sexual relations, and protection from the violence of nature. Music, in its origins—as we know them today—was more a matter of mystery than of knowledge. And it would be fairer to say that that knowledge, rigorously cataloged and learned, allows us access to the mystery of our existence. That is why I have used the word “knowing,” which seems most apt to me. I will, however, continue to use the term “knowledge” in order not to stray too far from our subject, reserving the right to use “knowing” when I think it helps to clarify matters.

In the West, the Christian church used Greek modes in a peculiar way, through what they called octoechos. These were: Dorian or protus (d–d), Phyrgian or deuterus (e–e), Lydian or tritus (f–f), mixolydian or tetrardus (g–g), and the corresponding plagal modes a perfect fourth lower. The modes can be told apart by the location of the semitone. Each mode has two key notes: the finalis on which it ends, and the repercussio (or corda di recita) around which the melody is constructed. Those were the denominations—erroneous with respect to the original Greek modes—that predominated and later became the basis for polyphony and the studies of our harmony and counterpoint. Several modes were excluded because they were considered too upsetting for the dignity required of sacred service. Music served the sacred text and, unlike music from Northern India, Tibet, and so on, it had to be understood by the faithful. The delicate metric inflections of the “neuma” must have favored the text and its understanding. This rigidity did not, however, impede variety: Ambrosian, Mozarabe, and Gallican chant, among others, were eventually unified as Gregorian chant, following considerable struggle by known figures and the risks of excommunication.

Around the twelfth century, European polyphony was born in Northern France—every day, more people share the opinion that polyphony originated in Africa, but that is another story—and from that moment, the relation between music and text began to change. The words began to be incomprehensible, as they were being sung by more than one voice, but the expressive capacity of the music expanded enormously, threatening the liturgy’s monopoly on music. The troubadours may have been the first to make deliberately secular music. In the eleventh century that is already true “accompanied melody.” Later, we find it explicit in Dante (“Purgatory,” Canto II), when the poet encounters a musician friend, Casella, who had put some of his poems to music when he was still alive. Dante asks him: “…ti piaccia consolare alquanto / l’anima mia, che, con la mia persona / menendo qui, è affanta tanto!” The musician sings Dante’s poem, Amor che nella mente mi ragiona, whose music is now lost.

I regret only being able to mention the fascinating fact that music’s independence from liturgy—that is, a secular text set to music with the accompaniment of an instrument—is not European. In fact, it came to Europe as a result of the Crusades on one hand, and the Muslim presence in Spain on the other. In both cases, its provenance was from ancient Persia—including the instruments—and it was brought by religious dissidents (the Cathars, etc.), with the glorious exception of the “Canticles,” where there was no persecution at all, perhaps because of their explicitly sacred contents.

Music’s awakening as an autonomous art—that is, free of liturgy, and even of text—was relatively late in the West, even though, thanks to its subtle polyphonic techniques, it was always considered the most emotive of the arts, essential to, and inseparable from, both poetry and religious uses.

This interdependence of text and music, both religious and secular, is not the only one that has characterized our art. Music has had many adventures in other cultures, and I would like to mention a few to demonstrate its ductility and its volatile—that is, protean—character. Here are two examples:

In Genji (Heian dynasty, tenth century) Lady Murasaki (Murasaki Shikibu) tells us how there was an entire repertoire of outdoor pieces for the fue transverse flute. This repertoire varied with the seasons, taking into account the natural sonic setting brought about by each one. This music is still played and I had the good fortune to hear the admirable Suiho Tosha perform it in Kyoto. Obviously, this idea is rooted in the Shinto religion.

There are other musical forms that are not satisfied to be played outdoors; they aspire to a meticulous description of certain aspects of reality: rain, a spider balancing on her web, a child crying, a young man attempting to sneak into the “house of women,” and so on. I am referring to the traditional music of the Aré-aré (Hugo Zemp, “Melanesian Pan Flutes,” Musée de l’Homme 1971) with its pan flute ensembles (au tahana and au paina).

This is a precious example of how a descriptive music, understood as such by its creators, signifies absolutely nothing to those outside its culture, except as an exquisitely beautiful object lacking any meaning. And we find this divorce of aesthetics and original meaning innumerable times.

I would not want these divagations—which I do not consider as such—to be mistaken for useless erudition. With them, I am attempting to show, on the one hand, that it is impossible to find the “frontiers” of music—other than purely physical ones—and on the other, that the word “knowledge” suits neither its nature nor the effects it produces on listeners. Its reality is too varied—not contradictory—for anyone to seek a unity that could only mutilate it. And that is enough about this matter.

When instrumental music was fully established in Europe (more or less in the fifteenth century), the rules of composition were defined with exquisite care. At the same time, new genres were being invented that favored emotional expression over everything else.

From then on, something uniquely European began to take shape in the West, so much so that, for many enthusiasts, that “something” is synonymous with music. As you will have guessed, I am referring to harmony, which replaced “modes.” Harmony established the precise functions of intervals, measuring their capacity for movement or repose. The origins of this movement are in the polyphony that preceded it, but now it serves tonality and its fluctuations—what are called “modulations.” Harmony has been compared to perspective, though the latter concerns space, while the former concerns time. Undoubtedly, it is the most specifically European musical technique ever created by the West, although it meant abandoning a great deal of popular music, which was frequently based on the old modes.

As harmony adapted to the rules of the former counterpoint—and vice versa—a series of procedures emerged that became the very core of European compositional teaching. One of the milestones in this teaching was Johann Joseph Fux’s Gradus ad Parnassum (1725). For a very long time indeed, almost every later composer was respectful of the old master, even if they took certain liberties. Just a few years ago, György Ligeti (1978) told Péter Várnai (Ligeti in conversation, Eulenburg, London, 1983) that he asked his advanced composition students to be “familiarized” with that venerable text, after which they could do whatever they wanted. That piece of advice, I might add, ran throughout the nineteen century and, as we have seen, much of the twentieth as well. One might ask why, and the answer has to do with the “craft,” I have so often mentioned. With Fux in hand, the solidity of the building is assured, though it offers no guarantee that the building will be interesting. But neither Fux, nor any other theoretician, has to address that issue: it is a matter for the artist… who learns discipline from him, even when that artist is undisciplined by nature, as was the young Debussy, for example. To put it clearly, once and for all: Fux and his innumerable offspring were, and may still be, essential for their role as a negative pole.

The attacks began only about a hundred years after it was published: late Beethoven, Romanticism, Wagnerian opera, French harmonic, and timbral subtleties, the nationalists—especially the Russians—the first central European atonalities (though not what followed them, as we will see below), as well as—from a different standpoint—the Universal Exhibitions, which brought colonial art to the metropolises, and so on. All of this produced an unstoppable fermentation that didn’t eliminate it, but did change its meaning. Instead of a body of essential norms, Fux became a reference point for our old identity—something worth knowing if we want to avoid any missteps. Quite simply, it became a source of practical “knowledge” (which is no small matter).

The last hundred years or so of music’s history is already present in what I have just written. The structures of classical harmony—and its formal consequences—collapse, and the causes are both internal—its developmental dynamics—and external—agents from outside.

Let us consider each for a moment. The internal cause stems from the same cultural setting as the model: the Germanic world. Naturally, I am referring to the School of Vienna and its “trinity” of Arnold Schoenberg, Anton Webern, and Alban Berg. Their primary objective was to dissolve tonality into what Schoenberg called “pantonality”—also known as “atonality,” a term he considered inexact. From 1906–1909 (with his Kammersymphonie, op. 9, or even his Second Quartet, op. 7) to 1921, when he defined his compositional system (his “technique for composing with the twelve tones” generally called “serialism” in English), the three Viennese composers made an enormous number of technical innovations. But Schoenberg was also an extraordinary teacher, with an absolutely foolproof classical training, despite the fact that he was practically self-taught. His invention of twelve-tone technique was a way of prolonging classical techniques in a new context. His Pierrot Lunaire (1912), which precedes serial technique, is a fine example of how he was already combining the most risky new techniques with the oldest ones. The School of Vienna had a very clear “mission” that consisted of two complementary facets: first, using new means to make advances in musical expression; and second, recovering and resuscitating classical procedures from the great Germanic school, using up-to-date contents. Thus, we see that their serial, and even pre-serial, compositions return to severe counterpoint, classical forms, and so on, in order to avoid a break with the past, prolonging what they considered German-Austrian music’s supremacy over all others. Despite Nazism, which prohibited their music as “degenerate,” “Bolshevik,” and so on, and forced Schoenberg into exile; none of them renounced the idea of considering themselves the only true bearers of the central-European musical heritage. The School of Vienna’s attitude was of a very high ethical quality, colored by a rather ingenuous nationalism, clearly not very folkloric, but absolutely demanding of itself. Very much in the sense of Beethoven, their music was their moral—intransigently so—in the face of a hostile world. Sad to say, Karl Popper’s aggressive reflections on the music of the School of Vienna are a model of incomprehension and arrogance.

Among the external causes, none was as powerful as the knowledge of other cultures and the changing attitude toward them. The disdainful attacks of Berlioz, Gianbattista Vico, and many others, at first gave way to curiosity and later enthusiasm. It may be difficult to find a European composer of a certain stature from the last seventy years—though not the German-speaking ones, as clarified above, except for Stockhausen—who has not been influenced by music outside our traditional Western teachings. It is essential to reflect on this fact.

1. These musical forms have been absorbed by the West. Some non-Western countries—Japan, Korea, Morocco, China, and so on—have undoubtedly assimilated certain aspects of Western music. But composers from those countries have done so from the perspective of our tradition. Let me explain: Toru Takemitsu, for example, uses Japanese instruments, scales, and even “time sense.” But the results of his work are part of the Western symphonic tradition. His music is not included in the Japanese tradition; it is not a part of gagaku, kabuki, or the repertoire of the beggar monks with their shakuhachi—the end-blown flute he uses in his works. Allow me to furnish an illustrative anecdote: when Toru Takemitsu began studying music in Tokyo, his attitude was a total rejection of the Japanese tradition—those were the post-war years. He moved to Paris to broaden his studies, and it was there, in the sixties, that he discovered the musical tradition of his own country and his conversion took place. This is a vivid anecdote, and something very similar happened with Ahmed Essyad and Morocco… and with leading current composers from Korea, China, and so on.

2. Taken one by one, these musical forms cannot be translated into each other. For example, it is difficult to imagine how the vocal polyphony of the Aka Pigmies of Central Africa could be enriched by listening to and studying the drums that accompany the action of Kathakali theater from Kerala (southern India), or vice versa. As I say, these traditions are untranslatable.

On the other hand, this is not the case for Western music. And we can see and hear this every day in both theater and music. The reason is clear: Westerners have abandoned the extramusical contents that, like all others, those non-Western musical forms include. This should come as no surprise, given that we have done the same thing with our own music. Consider the ever-more-frequent use of medieval techniques in current music. And even more so, consider the neoclassical music of the nineteen twenties—the towering figure of Stravinsky—and you will see that this in not a new phenomenon in the West. This should not, however, be seen as a criticism on my part, but rather as an effort to understand the direction of our music’s evolution.

3. Our “consumer music,” with its exceptional means of distribution—which makes it an indicator of our wellbeing and power—is invading the planet and may well be the only part of our musical history known by all peoples. Moreover, the mutual incompatibility between musical forms mentioned above also occurs in the West, between our so-called “classical” or “straight music”—horrid labels—and our “consumer music.” It is enough to know what the greater part of Western youth considers “its” music, “its” means of expression. Allow me to eschew considerations as to the provenance, possible consequences, and musical characteristics of this fact (at the beginning of this text I asked permission to do so).

In the early twentieth century, at the onset of this positive encounter between our musical tradition and music from other cultures, something else began that is only, or almost only, known by specialists, although in my opinion it is very interesting because of its direct relation to the interpretation of music and its frontiers.

In Germany and France, musical research centers were founded that drew on the possibilities offered by the advent of recording techniques—rudimentary at the time, but now efficient—and comparatively safe travel to remote areas. The object of those centers was to study music as a global phenomenon and to draw conclusions, where possible. In Berlin (1919), Curt Sachs founded the Institute of Comparative Musicology. In Paris, André Schaeffner created the Department of Ethnomusicology at the Museum of Man (1929). In Barcelona, the exiled musicologist, Marius Schneider, did the same in 1944. Eleven years later, he was to found the School of Cologne for the same purpose. In my opinion, those are the three names that best define this search, this effort to find a “general part” of music, collecting an enormous quantity of data—before computers even existed—that was not treated merely as isolated facts; contexts were taken into account and common links or significant contrasts between different materials were sought out. Some of the questions addressed include: what does the different use of the voice in different epochs and cultures signify? How has the cadential value of the descending perfect fourth been used? How do isochronies and heterochronies compare? And so on. Some researchers went even farther. Marius Schneider tried to draw links between, on one the hand, rhythms, intervals, cadences, and so on, and on the other, signs of the zodiac, animals, constellations, iconography, etc. André Schaeffner did the same with musical instruments, studying their origins, evolution, symbols, tuning, social significance—religious or otherwise—and so on.

This group of musicians has carried out a very worthy job of conserving, studying, and publicizing music that is rapidly disappearing. They have struggled to create a “science of Music” that aspires to give global meaning to our musical history. And they are not alone in their aspirations. A fervent Sufi reached the same conclusion from the perspective of his tradition. That perspective has not kept Karlheinz Stockhausen and numerous rock musicians from devotedly studying the writings of Hazrat Inayat Kahn, who was born in the early twentieth century in what is now Pakistan. His underlying idea is the same—music is the only vehicle for wisdom—but his starting point is not. European musicologists sought to establish a scientific basis—rather sui generis, perhaps—for their work. But Kahn calls simply for common religious faith. And we had best avoid the world of Pythagoras, on one hand, and ancient China, on the other…

The procedures and results of this admirable group of musicologists have frequently been branded as “esoteric” or “magic,” and even dilettante. I think they have been attacked because their work on interpreting the phenomena of culture through music has been disconcerting to many, due to its unusual nature. To me, as a musician, they seem neither more nor less magic than Roman Jakobson’s approach to linguistics or Claude Lévi-Strauss’s work on family structures. Are these mere questions of affinities? No. Any theory that seeks to be holistic will overlook certain things, and may even be ridiculous. Let the guiltless party throw the first stone…

The explosion of science in the nineteenth century had important consequences for music, its meaning, and, most of all, knowledge of its materiality as sound. One of many examples is the contribution of the German physicist, Hermann von Helmholz (d. 1894), which was extremely important in stimulating the imagination of many composers more than fifty years after he published his discoveries. After analyzing hearing and studying timbres and pitches, he hypothesized that they are all related and that there could conceivably be a music in which this relationship had a function. Moreover, he set the bases for psychoacoustics, which is a landmark for composers in their treatment of the materials they use. It does not take much insight to realize that one of the origins of Stockhausen’s music—French Spectral composition—and its countless consequences lies in the work of Helmholz and his followers (many of whom do not even realize they are his followers).

Paralleling this scientific research, musicians themselves needed to enrich their expressive media. A simple enumeration of the inventions they thought up and the results they achieved would already take up too much space here, but I will mention some of the most relevant. The first consists of the thousand transformations of musical instrumentation, with an emphasis on percussion. This led to an endless number of masterpieces, too long to list here, that are already a part of common compositional practice.

We cannot overlook the intonarumori of the Italian Futurists (Luigi Russolo, 1913), which were little more than curiosities, but indicate a renovating stance.

The arrival of technology generated an authentic revolution. First, in Paris, the GRM (the Musical Research Group led by Pierre Schaeffer [1910—1995]) and Pierre Henry (1922-) ushered in musique concrete during the second half of the forties. Initially considered an “other art” halfway between cinema, radio reporting, and music, it finally became a part of the latter. Its raw materials were real sounds/noises, recorded and treated using electro-acoustic devices: recorders, filters, etc. The GRM even invented one device, the phonogène, which is now a museum piece, but played a key part in its day. Soon thereafter, in 1951, Herbert Eimert (1897–1972) and Karlheinz Stockhausen (1928–2007) founded the Electronic Music Studio at Radio Cologne, using oscillators, filters, and many other devices.

Together, musique concrete and elektronische Musik merged to form “electronic” or “electro-acoustic music,” which rapidly spread throughout the technologically developed world: from Stockholm to Milan, from Lisbon to Warsaw, Montreal to Buenos Aires, Tokyo to New York, Sidney to Johannesburg, and so on. Its technical advances were extremely rapid and what had begun as a craft quickly became a world of discoveries in constant evolution. Masterpieces soon followed. The best known—and rightly so—is Karlheinz Stockhausen’s Gesang der Jünglinge (“Song of the Adolescents,” 1955, Cologne).

In 1960, the sound engineer, Robert Moog, designed the first Moog Synthesizer in Buffalo, New York. This flexible device made it possible to use a synthesizer “live,” that is, like any other instrument. It could be connected in multiple ways, including to a computer, and it was so simple to control that it made electro-acoustic media available to an unlimited public. Suddenly, what had been considered the cutting edge of the avant-garde grew vulgar, falling directly into the hands of “consumer music.” Free electro-acoustic creation was still possible, but grew increasingly difficult.

In 1955, at the University of Urbana (Illinois), Lejaren Hiller (New York, 1922) programmed a computer, the ILLIAC IV, to reconstruct traditional musical structures: harmony, form, and so on. The result was the Illiac Suite for string quartet. Hiller privately confessed that he was not trying to make music, but rather to demonstrate the unknown capacities of the machine. Shortly thereafter, though, the digital-analog converter was designed, allowing the machine to make sounds. Around 1965, John Chowning at Stanford University (California) designed a computer with frequency modulation, allowing the machine to broaden its possibilities to include any timbre—instrumental or invented—meter, number of voices, and so on.

And here it is prudent for me to stop, because what follows—and we are in the midst of it right now—is the computer invasion, which gives anyone access not only to any sound material, but also to anything related to music: publishing, listening, mixing, combinatoriality, meter of any desired degree of complexity, and so on. A “thing” that reminds us of music—because of its aural content—can be generated today by anyone who can handle a machine with a certain degree of skill. I am not speaking of a “work” but simply of the possibility of making “something.” Nevertheless, that possibility does not seem to be of much help to the layman when trying to achieve what, with all due respect, could be called “quality.”

Obviously, the machine has made it possible to do things that could only be dreamed of before: transforming an instrumental or vocal sound at the very moment of its production or doubling it; the interaction of pitches at different listening levels; results never heard before—literally, as there had never been any way to produce such sounds—either totally unknown, or of known origin, but unrecognizable; transformation of any constituent element of sound a varying speeds, and so on. The list is endless. Such was the enthusiasm for the “new music” that in the fifties, an illustrious composer—I’ve forgotten his name—stated, with moving forcefulness and faith, that “in ten or twenty years, no one will listen to the music of the past anymore.” This never came to pass. On the contrary, “classical” music from the world over—from Bach to Coptic liturgy—is being heard more than ever, so the facultas eligendi is safely installed. I believe that in time the use of computers for music will lead to something else: the presence of a medium so powerful doesn’t seem likely to impede the existence and development of music whose means of expression are more traditional. As always, the most probable outcome will be an unpredictable mixture.

This “bird’s eye view” of music, though hurried and necessarily partial, has, I believe, been sufficient for the job at hand. One thing is clear: the limits of musical knowledge—in the sense of what can be learned—has expanded so much that is difficult to decide what is necessary and what is accessory. We should also point out something important, though rarely mentioned: techniques—in plural—of musical composition have proliferated to an unbelievable degree in the last 40 years, and I am speaking only of the West. Beginning with an illusory unity: the most restrictive version of the serialism that was the son or grandson of the School of Vienna—cultivated by the so-called Darmstadt School (Germany) and its courses founded by Dr. Wolfgang Steinecke in 1946. This severe technique simply self-destructed in the late fifties. Since then, it would be no exaggeration at all to say that there are as many compositional techniques as there are significant composers.

I will not attempt to explain why things exploded in the sixties—that would be a different article altogether. Moreover, that was a decade filled with revolutionary events of every sort. Those storms have calmed and in the last twenty years the waters seem to be running more smoothly. But this was not due to any return to order—which would have been as pretentious and extemporaneous as Jean Cocteau’s—but rather to a healthy systole after the Pantagruelian diastole.

I mentioned above that Western composers of recent years have done away with the extramusical content of music. That is, music does not “represent” anything except itself. Is that true? In my opinion, yes. And I would have to add that it has always been true, especially in the most illustrious cases, where music has the most power to move us. Thus, when non-European musical forms began to be appreciated and assimilated by Westerners, they were not appreciated because of their non-musical contents, but for the beauty and interest of their sonic contents: our ears were already prepared for them.

Our composers have always known this—how could they not know, or at least intuit it?—even when they wrote descriptive music. Sixteenth- and seventeenth-century madrigals and opera are paradigms of what I say. The word stimulates the composer’s imagination, but the music born of that stimulus is not a translation of those words. That would be both impossible and frivolous. The past, perhaps wisely, did not argue about this at all. It was clear that an adequate sonic order was expressive per se when done with imagination, freshness, and mastery (I am deliberately ignoring the untimely arguments about prima la musica, dopo le parole—or vice versa. They did not affect composers).

In our time, such arguments have arisen, however. Some composers thought music had to renounce any sort of expressivity, including its own (remember the rather comic indignation of Franco Donatoni at the emotive power of Senza Mamma from Puccini’s Suor Angelica). That position was also taken by young Boulez in his Structures I for two pianos (1952), though certainly not in his following work, Le Marteau san maître. But in my opinion, even in the line of composition in which the author does not, in principle, take any interest in the expressive dimension of a sonic order, if that order is successful (in terms of originality, perfection, and depth) it will transmit a sort of emotion to us. Perhaps this is unwanted, but it is inherent to the material and, of course, impossible to put into words. Maybe the error of Structures I (Boulez always considered them an experiment) is that the sound is ordered in a purely numerical-combinatorial—rather than musical—manner, which makes the results unintelligible. With all due respect, certain works by Xenakis have the same problem.

Moreover, it is more than probable that the blossoming of musical techniques mentioned above has its origins in the emphasis that recent—and not so recent—composers have put on pure musical material as the main axis of creative impulse (Debussy must be turning in his grave…).

And so, we return to our starting point: what can be known with, or through, music? What does “Frontiers of Knowledge” mean when speaking of music? The “Frontiers of [Musical] Knowledge” would be those that define the capacity of scholars and creators on one the hand, and the receptive capacity of listeners on the other. In the latter case, the idea of knowledge and its frontiers will be identical to the capacity to experience deep aesthetic feelings, which enrich us personally, though rarely collectively (watch out for mass emotions!), despite the apocalyptic halls in which music that was intended to be heard by no more than ten people is so often listened to by crowds of ten thousand…

It remains to be seen whether this “emotion” could be a form of knowledge. If it is—and I believe it is: see what I wrote at the beginning of this chapter—it belongs to a different sort of cognizance. It does not seek objective, verifiable truth quite simply because that kind of truth does not exist in art. And I dare say—forgive me for talking on so much—that it is knowledge that stems from life experience, not from studying. As I said, studying—and its delights, for it has them—are for professionals. The lived, enjoyed, and instructive experience of sensitivity—without excluding scholars, needless to say!—is mostly for others: those to whom the artist offers his work. And with the passing years—almost always, many of them—a musician’s contribution becomes part of a collective identity, part of that collective’s “knowledge.” The collective recognizes itself in that contribution, and that is the “truth” of art and music. Whether that truth is valuable or simply mediocre and trivial will depend on the collective’s education. Moreover, in a healthily pluralistic society there are always many collectives. What is more, collectives united in shared recognition do not have to coincide with state, religious, linguistic, or any other sort of frontiers. They are linked by a shared emotion, a shared “knowing” of emotions.

I am finishing, and I must do so with a question. Nowadays, the frontier of this knowledge (recognition, knowing) is undergoing sudden, unforeseeable, and possibly uncontrolled changes. Musicians—most of all, composers—live in a constant short-circuit (as I already insinuated). This is not comfortable, but there is not time to get bored. Thus, I point it out without fear…but with some uneasiness.

Comments on this publication