One name that has already made the list of celebrities who have died in 2020 is that of Florian Schneider, co-founder of Kraftwerk, a pioneering band in the exploration of electronic music for the general public. Techno sounds like those produced by Kraftwerk are what we traditionally associate with the use of digital technology in music. And yet we would be deluding ourselves if we believed that electronic manipulation is not widespread in all genres of pop music. In particular, for decades the music production industry has made intensive use of what was once an open secret, Auto-Tune, a pitch-correction tool that improves the performance of vocalists, even used by those who criticise it, and which has its curious origins in technology used to search for oil and gas.

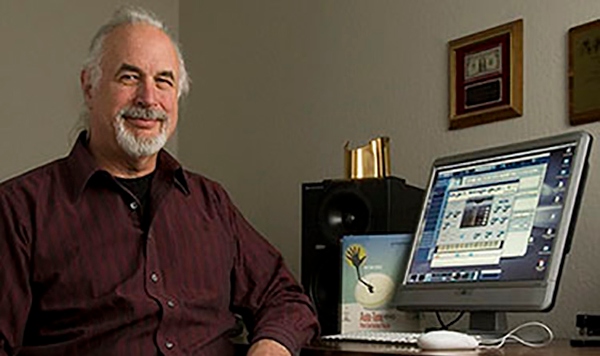

In the mid-1970s, engineer Andy Hildebrand was awarded his doctorate in a peculiar subject, the mathematical analysis of the populations of the alfalfa weevil, an agricultural pest. But by then the diversity of his interests was already revealing itself; he had participated in the development of pre-GPS navigation systems, and with his freshly-minted thesis under his arm he landed in the Texas oil patch to search for hydrocarbons underground by studying seismic waves.

The sound of the 21st century

His handling of mathematical algorithms, his experience with acoustic signal processing and his long-standing passion for music all came together one day in 1995, when during lunch with some friends and their wives, Hildebrand asked the assembled company what needed to be invented. One of the women half-jokingly suggested a device that would allow her to sing in tune. By then, Hildebrand had made his fortune with his seismic models, but he had already left geophysics to turn to music signal processing technology. Five years earlier, he had founded Antares Audio Technology, focusing on other projects. But several months after that lunch, it suddenly occurred to the engineer that he could apply his knowledge to achieve what that woman had asked for, pitch correction when singing, a goal for which no technology was yet available.

That’s how Auto-Tune was born in 1997; while originally a machine, today it’s usually a plug-in for digital audio workstations. It was a runaway success from day one. Music producers quickly began to take advantage of the invention to avoid the tedious method used at the time to produce a song: cutting and pasting from countless recordings until the final perfect version of a song was obtained; by running the song through Auto-Tune, the system placed each syllable in exactly the right note. Hildebrand’s tool has been described as the greatest pop innovation of the last 20 years, or even as the sound of the 21st century.

Cher’s secret and her Believe

Auto-Tune ceased to be a secret when its use was perverted, with unusual results. In 1998 singer Cher released Believe, a worldwide hit that left listeners wondering how it was done. Robotic voices were not new to music; the Kraftwerk themselves had popularised voice processing through the vocoder, a synthesiser invented as early as 1938, back in analogue times. But the effect on Cher’s vocalisations was something different and entirely new. Despite this, the producers tried to hide the secret, claiming they had used a type of vocoder pedal.

However, the truth soon came out. Auto-Tune has a regulator for the transition speed between the notes, from zero (instantaneous) to ten (slower). Instead of applying just the right dose to smooth the transitions, the producers of Believe turned the knob to zero, achieving those instantaneous jumps from one note to another that gave the voice that artificially crystalline quality. As every good idea later has its legion of imitators, the extreme use of Auto-Tune became so popular that it was even used, according to Hildebrand himself, in a Muslim call to prayer. Even those who have denounced it, such as rapper Jay-Z or singer Christina Aguilera, are also known to have used it. In 2010, Time magazine included Auto-Tune in its list of the 50 worst inventions. And yet despite this, it is said to be used in 99% of modern pop music.

Nowadays, the use of Auto-Tune is more alive than ever before. For some experts, the technology still has more surprises up its sleeve: “People are still finding new things to do with the electric guitar, which has been with us for 70 years or so, much longer than Auto-Tune,” music and sound expert Yanto Browning, a professor at Queensland University of Technology, told OpenMind. “I think it’s very dangerous to say that any technology is creatively out of date.” “I don’t know what the future holds for pitch-tracking and pitch-correction technology, but it certainly doesn’t preclude musicians finding new and interesting applications for these kinds of signal processing tools,” Browning adds.

Artificial Intelligence, the future of Auto-Tune

Although there are competitors to Auto-Tune today, the future of these technologies may lie where so many others do as well: Artificial Intelligence (AI). At Indiana University’s Department of Intelligent Systems Engineering, the team led by Minje Kim is working on an alternative to Auto-Tune that uses self-learning neural networks to correct the intonation. As Kim explains to OpenMind, Auto-Tune needs user control to set the note to its correct frequency. “Our machine learning system is trained in a supervised fashion using high quality singing data, but once it’s trained it doesn’t need a supervision to perform autotuning,” he summarises. “It relies on the AI’s decision, so that the entire process is fully automatic.”

In addition, this system, called Deep Autotuner, offers flexibility that Auto-Tune lacks, Kim’s PhD candidate and system manager Sanna Wager explains to OpenMind. “The measured fundamental frequency of a tone is often different from the pitch we perceive,” she says. This subtlety escapes Auto-Tune, while the proposed model “incorporates psychoacoustics, and it learns musical intonation patterns directly from real-world examples of in-tune singing.” On the other hand, Wager adds, Auto-Tune treats notes discreetly according to the 12-semitone Western musical scale, like the keys of a piano, so it “can be musically limiting.” In contrast, Deep Autotuner creates a continuous range of frequencies like that of the human voice. This also allows it to be trained for “some other musical cultures such as Classical Indian music, which subdivides the octave into a larger number of subdivisions.”

Nevertheless, although AI is increasingly present in creative fields such as music, this does not imply that it will dehumanise it, a frequent accusation among Auto-Tune’s detractors. “We believe that AI systems can extend to many other use cases to attract more music hobbyists, so that they can still enjoy making and playing music without being overwhelmed by the technical issues,” Kim notes. But above all, he adds, “we also believe that music is a sophisticated human activity that AI cannot easily catch up with in terms of quality.” Both musicians and sound engineers will continue to be, he concludes, irreplaceable.

Comments on this publication