“Having your head in the clouds”, “being on cloud nine” or “every cloud has a silver lining” are some of the usual expressions associated with one of the most common atmospheric phenomena. Although water clouds are currently exclusive to the Earth, clouds made of different substances can also be found on other planets: Venus, for example, is covered with dense clouds of carbon dioxide that hide its surface, and Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus and Neptune have clouds composed of hydrogen and helium.

Just as we sometimes have fun searching for exotic shapes in the clouds, we can also amuse ourselves by differentiating them and discovering what each type reveals to us. That is what the English chemist Luke Howard (1772-1864) used to do at the beginning of the 19th century. Considered the father of meteorology, he divided clouds into four major categories (cirriform, stratiform, nimbiform and cumulous) and launched a scientific field to learn how to read them, using their varied and suggestive appearances to predict what meteorological changes they are announcing to us.

Made up of tiny particles of liquid water and ice, Earth’s clouds are generated when the water vapour that emanates from rivers and seas cools and condenses when it reaches the highest and coldest layers of the atmosphere. From there, its shape and its story take very different paths:

Cirriforms: curls of hair that cover the sky

With the shape of curly hair, but composed of ice crystals, cirrus clouds are the most representative of this category. They can cover the sky between 5 and 15 kilometres in height. They are high, clear, thin and delicate clouds that frequently announce a meteorological change for the worse; in general they are followed by precipitation and temperature drops in the 24 hours after their appearance.

When light interacts with the ice crystals that make up cirrus clouds, optical phenomena can occur as unusual as the sun dog (parhelion), the simultaneous appearance of images of the Sun reflected in the clouds, and the halo, a pale circle around the discs of the Sun or the Moon.

Stratiforms: bed of clouds

These are broad clouds with diffuse contours that develop horizontally, so they spread as if they were a bed or a layer. Within this category are found four types, according to their height: stratus, altostratus, cirrostratus and nimbostratus. The latter, unlike the previous ones, also develop vertically and totally impede the passage of sunlight, which is why they are very dark clouds. The nimbostratus always produce precipitation that is usually continuous and not very intense.

Until well into the twentieth century, the formation of clouds was understood as an advanced phase of fog, and clouds were considered to be fog at higher altitudes. The French astronomer Camille Flammarion (1842-1925), in his treatise The Atmosphere, states that “even when there is no essential difference between the fogs and clouds (…). The first is immobile, the second mobile.” Nowadays, fog is considered a type of cloud with its base on the ground or close to it, with little vertical development, and it is categorised with clouds from the stratiform genus.

Nimbiforms: the anvils of the storm

From the Latin nimbos, meaning rainstorm, this type of cloud is what generates the most precipitation. In this category is the cumulonimbus, the largest and most powerful cloud that can be seen, which even airplanes should avoid. This “queen of the clouds” has strong currents in its interior with unpredictable winds that violently move the air from top to bottom and from bottom to top. These clouds usually generate heavy rains and thunderstorms, associated with hail, waterspouts and tornadoes. The water that a medium cumulonimbus cloud contains could fill seven Olympic swimming pools.

With a base located over 1,000 metres high, the top of the cumulonimbus can reach 20 kilometres. Its vertical growth is only interrupted when it reaches the tropopause, the upper limit of the troposphere, the innermost layer of the atmosphere that goes from the ground to the stratosphere. A fully developed cumulonimbus cloud is anvil-shaped.

Cumuliforms: mountains of cotton

These are isolated clouds in the shape of a mountain or a dome of cotton, which have a well-defined contour and exhibit a great variety of sizes and thicknesses. The cumulus clouds, the most characteristic clouds of this category, appear especially in hot times of the year and can occupy a space that ranges between 500 and 6,000 metres in height. With a significant vertical extension, they can be generated in isolation or associated with others in rows or groups. Depending on the atmospheric factors that surround them, such as humidity, cumulus clouds can give rise to cumulonimbus.

Shortly after the Second World War, scientists began to theorise about the idea of what is now known as “clouds seeding.” This process involves using silver iodide, dry ice or frozen carbon dioxide to artificially condense the vapour. These substances are associated with water molecules and provoke precipitation. The usual thing is to spray them on cumuliform clouds from small planes or rockets. In February 2018, for the first time, a group of researchers from the University of Wyoming (USA) managed to seed clouds to generate snow and monitor the entire process, from the formation of ice crystals in the atmosphere to their precipitation.

Stratocumuliforms: layered balloons

In addition to Luke Howard’s four original categories, the current international cloud classification system recognizes a fifth division, the stratocumuliforms. They are globular clouds that can develop in layers. In this category are, from lower to higher, stratocumulus, altocumulus and cirrocumulus. A stratocumulus is a large low cloud of rounded shapes, while altocumulus and cirrocumulus are small stratocumulus distributed in groups and aligned.

From altocumulus come some of the rarest and most extravagant clouds. The lenticulars, for example, have the shape of a flying saucer and are usually formed in mountainous areas. The mammatus, meaning “mammary cloud”, associated with tornadoes, have the appearance of pouches hanging underneath the base of the cloud, like the udder of a cow.

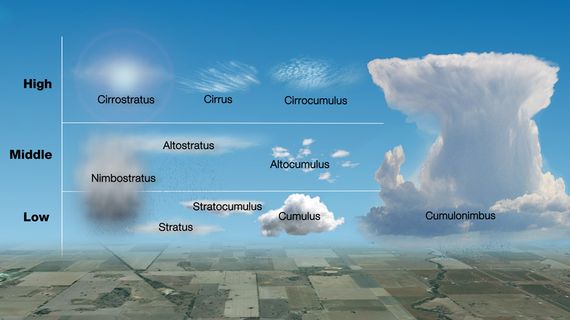

Low, medium and high

The 1956 edition of the International Clouds Atlas published by the World Meteorological Organization defined the ten basic cloud shapes that we have just reviewed, based on Howard’s classification and according to the height they reach in the sky. Thus, low clouds, which are those below 2,000 metres, are strata and stratocumulus.

The medium clouds are those that are generated between 2,000 and 7,000 metres; here you can find the altostratus, the altocumulus and the nimbostratus. The high clouds, which are formed above 6,000 metres, are cirrus, cirrocumulus and cirrostratus.

The last two types are the cumulus clouds and the cumulonimbus, with their impressive vertical growth that situates them from the lowest to the highest clouds.

Endless shapes and sizes for a transient daily show that floats prodigiously above our heads.

Comments on this publication