Chemists may know Henry Cavendish (10 October 1731 – 24 February 1810) as the discoverer of hydrogen. For biologists, his name will evoke the laboratory at the University of Cambridge where the structure of DNA was discovered. The Cavendish Laboratory is the Department of Physics, a tribute to the figure physicists remember as the man who “weighed the world”. This mark on different branches of science shows why he has been called “the foremost British natural philosopher of his age”; fortunately for him, you could then be a great influencer without being liked.

Great historical figures in science were so because they didn’t need to work and their wealth could afford them expensive laboratories; in the old days, it wasn’t who wanted to do science, but who had the means to do it. Names such as Darwin, Newton, Boyle, Lavoisier and Franklin are examples of this figure of the “scientific gentleman”, and both Cavendish and his father were members of a family with long aristocratic roots. The father, Lord Charles, was widowed when his wife died shortly after the birth of Henry’s younger brother Frederick. With two sons to bring up, Lord Charles eventually abandoned politics, the traditional occupation of his lineage, to pursue science as a hobby, an interest he shared with his son Henry.

Conditioned by his personality

The family fortune enabled the Cavendishes to build their home laboratories. Their aristocratic roots gave them access to scientific circles and to the Royal Society, which in 1757 awarded Lord Charles the Copley Medal—its highest award—for his construction of thermometers able to record maximum and minimum temperatures; it should be noted, however, that Lord Charles, who was also known for his studies in electricity, was vice-president of the institution.

As for Henry, his scientific career was not exactly precocious: he never graduated from Cambridge, and it was Lord Charles who introduced him to the Royal Society when he was already 27 years old. But once he had embarked on this path, he threw himself into it with such gusto that not only did he commit all his time to it, but also a large part of his fortune, which only got larger thanks to family inheritances; from his early manhood he received an annual allowance of 500 pounds from his father, and in his forties he inherited an immense fortune from his uncle, which at his death was the largest deposited in the Bank of England. The French physicist Jean-Baptiste Biot said of him that he was the richest of the wise and the wisest of the rich.

But his biographies tell of a man who lived like a hermit: misanthropic, solitary, shy, reserved, taciturn, antisocial and dispassionate. He had only one suit, which was 50 years out of style, and wore an old-fashioned wig. He walked at night, socialised only with scientists, and was said to speak less than a Trappist monk. He was an inveterate misogynist: he disliked women so much that he left notes to communicate with his maids and had a special staircase built to avoid crossing paths with his servants; if a maid dared to appear in front of him, she was dismissed. His only portrait shows him in profile because he refused to pose sitting down. Retrospective analyses of his personality have diagnosed him with Asperger’s syndrome, now classified as an autism spectrum disorder.

An impressive scientific legacy

It has been said that his scientific work was so prolific and valuable not in spite of, but because of all his quirks: his life was “a single-minded dedication to comprehending the universe“. His science was everything, and he had not the slightest interest in other matters. From his early work in meteorology, his interests expanded to include astronomy, mathematics and physics, electricity and magnetism, mechanics and optics, and all without the pressure to publish. Indeed, much of his work only came to light more than half a century after his death, largely thanks to the efforts of physicist James Clerk Maxwell; Cavendish was found to have anticipated concepts attributed to other scientists, such as electric potential.

Cavendish is best remembered for his discovery in 1766 of the elemental nature of hydrogen, a gas produced in the reaction of acid with metals, which had been observed by other scientists such as Robert Boyle. Cavendish termed it “inflammable air”, although he mistakenly associated it with “phlogiston”, a hypothetical substance presumed to be responsible for combustion. In 1783, Antoine Lavoisier coined the term “hydrogen” (literally, “water-forming”) and claimed authorship of the discovery of the composition of water, but Cavendish had discovered it earlier, without publishing it at the time. He also clarified the properties of carbon dioxide and determined the composition of the atmosphere.

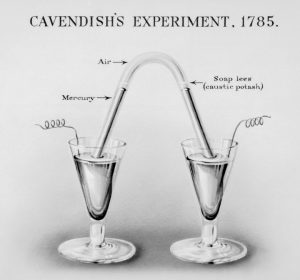

Cavendish is remembered by physicists as the man who weighed the world, thanks to his last major work, published in 1798, the experiment that still bears his name: he used a torsion balance to calculate the gravitational attraction between metallic spheres, allowing him to determine the density and mass of the Earth, which would later be used to calculate Newton’s gravitational constant. An impressive scientific legacy for a man who died as alone as he had lived. One day he said to one of his servants: ” Mind what I say—I am going to die. When I am dead, but not till then, go to Lord George Cavendish and tell him—go!” When the servant, intrigued, returned to the room some time later, Cavendish was dead.

Comments on this publication