Rural flight has been a persistent problem throughout history. In the case of Spain, we have documents dating back to the times of Philip II and Charles III, where policies and projects were rolled out to combat the phenomenon. These policies sought to promote settlement and development of the countryside by recognizing the importance of rural life as an integral part of the country’s social and economic fabric.

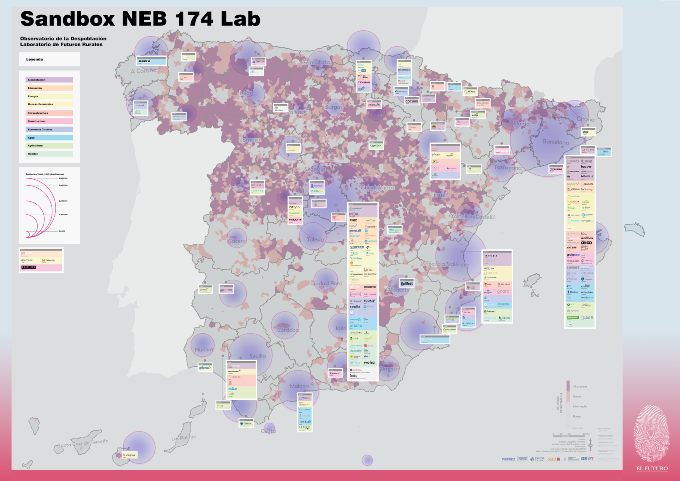

Map drawn up by Jorge López Conde and Lore Labropoulos showing 200 innovative projects in progress in depopulated areas, and the influence of cities. Source: Depopulation Observatory.

The demographic challenge is a persistent problem that has multiple facets to consider and new, seemingly intractable dimensions. Migration towards urban areas following the change of economic model ushered in by the National Economic Stabilization Plan of 1959 sent ripples across the country and introduced a new variant to the problem that persists today: the use of large swathes of Aragon, Extremadura or the Castile la Mancha, as a source of water, forest and energy for certain areas that underwent heavy industrialization in Madrid, Catalonia or the Basque Country. Spain’s entry into the European Union in 1986 and a new change of economic model pushed the countryside and rural living to the brink. Today, these are the same areas that have been damaged by large-scale animal, solar and wind farm projects. There will be a fresh exodus of talent, electrical or metabolic energy, to feed the cities of certain communities. This phenomenon not only affects Spain, but is a global concern, exacerbated by factors such as globalization—economic policies or technological change—whereby people spurn rural life and flock toward the city, as seen during Brexit or the Catalonia referendum.

In recent times, we have witnessed seeds of discontent among those still living and working in the countryside. It’s been a long time coming: in the case of Spain, the weight of the agricultural sector fell by 33 percentage points (pp) between 1960 and 2015, while the decline in the United States and the rest of Europe was 5 and 18 pp respectively. Agricultural workers accounted for 38 percent of the total workforce in Spain back in 1960, while the average for Europe was 21%, and 7% for the United States. Moving forward to 2015, employment in agriculture was just 5 percent of the total in Spain, compared with 3 percent in Europe and 2 percent in the United States. In Spain and Europe, 41 percent of farmers are over 65, 67 percent are over 55 and only 4 percent of farm managers are under 35. In addition, climate change has led to a 20–30 percent reduction in crop yields, such as olives and grapes. The Spanish Consumer Federation (FACUA) has reported an increase in the price of agricultural products by up to 875 percent from farm to supermarket, reflecting the inefficiencies of the food system, exacerbated by bureaucracy, unfair competition and agreements such as Mercosur. This has forced 5.3 million European farmers out of business between 2005 and 2020. In Spain, foreign investment has increased, with a 5 percent annual growth in land value, leading to the displacement of self-employed and local producers. Up to 30 percent of small and medium-sized farmers could be affected by these changes in the coming years. Worryingly, suicide rates among farmers are 20 percent higher than the national average within the EU.

If we lose the countryside, we stand to lose everything. Cultural landscapes have been built on the basis of territorial management. For centuries, food production has shaped the landscape, and now the industry faces the dual threat of globalization and climate change, which are two sides of the same coin. In many of the depopulated areas, huge swathes of forest have developed over the last fifty years or so. Various analytical models have confirmed that they may disappear due to the threat of megafires. It will be impossible to once again land back on earth, as Bruno Latour once remarked, if we lose the ancestral and traditional knowledge of bioeconomic and symbiotic management with the territory that our grandparents and great-grandparents developed as the last link in thousands of years of work.

HOW DO WE OVERCOME THIS PROBLEM?

After centuries with no solution in sight, and given the rising threat of populism, there is a growing recognition of the need to revitalize depopulated and/or rural areas, not only to preserve their cultural and social heritage, but also to harness their potential in terms of sustainability and innovative development. Various policies and projects running at global and local levels seek to create opportunities in these areas, aligning with broader initiatives such as the Green New Deal and the Sustainable Development Goals. The long-term Vision for rural areas or the Rural Development Programmes in Europe are good examples. In Spain, the Plan of 130 Measures to Meet the Demographic Challenge aims to position these “abandoned or empty” areas as a beacon demonstrating this paradigm shift. The Urban and Territorial Agendas 2030 target architecture and urban zoning and look to promote territorial and urban cohesion in Europe. The fight against climate change requires a change of economic model based on the circular bioeconomy and sustainable management of territories and cities.

The dissonance between Europe’s aspirations for sustainability underpinned by these policies and the practices of capitalism also reveals the need for a change of vision, in which architecture and rural innovation will play a crucial role in shaping policy and models for cities.

The challenge today is not to innovate in the Basque Country, Catalonia or Madrid; it is to innovate and design futures in depopulated areas below the EU’s 12.5 inhabitants per km2 limit for depopulated areas. Large areas of Aragon, Extremadura or Castile and León have ratios of less than six inhabitants per km2 (nearer to three), equivalent to the deserts of the Sahara or Lapland.

A NEW KNOWLEDGE FRAMEWORK

The document I prepared alongside Lore Labropoulos and a neural network, thanks to a grant received from the European Climate Foundation, is titled “Depopulation Observatory”. It is genuinely pioneering and one of its kind in the world. We studied an endless number of articles to overcome bias on the subject matter for the first time ever.

We tackle the problem of rural depopulation in Spain in a scientific and disruptive way by proposing hundreds of innovative and sustainable solutions (after analyzing thousands) that are now being developed in these areas, based on a theoretical framework featuring 12 narratives:

- Rural life as an opportunity.

- Rural progress through sustainability.

- It is an independent system that affords local communities greater autonomy in their processes and systems.

- It goes to the heart of the problem and has caught the eyes of the authorities, given the existing populist sentiment.

- Rural living is political.

- Defiance among local communities to certain changes.

- Rural living leads the food chain. “We are what we eat.”

- The Aspirational Image of the Rural World is all about the romantic perception of rural living held by city folk and the reification and simplification of all things rural.

- Architectural innovation is key to building sustainable rural livelihoods.

- Growing up in the Rural City sees the development of technologies and connections that generate new relationships and scales, also of innovation.

- New Generations: Focusing on the role of young generations in rural revitalization and shaping futures based on them.

- Circular Ecovillages: innovative and sustainable models as a platform for the design of communal living and rural and territorial development, focusing on bioeconomy, autonomy and the implementation of circular economies and programs such as permaculture, which entwines ecological and socially innovative practices to create resilient and self-sufficient communities.

A NEW ARCHITECTURE

Architecture and urban planning bring together the bioeconomy and the way we live life. Until May 12, the ICO Fundación museum will be hosting the exhibition ‘Pueblos de colonización. Miradas a un paisaje inventado,’ curated by Ana Amado and Andrés Patiño Eirín. The event is dedicated to the transformation process that rural Spain underwent between 1939 and 1971 at the hands of the National Institute of Colonization, which planned and oversaw the construction of new hydro power infrastructure and more than three hundred villages that mobilized 60,000 families.

The article titled “Franco’s 300 villages against depopulation” by Inmaculada E. Maluenda and Enrique Encabo ends with a profound message: “As the current drought in Andalusia or Catalonia shows, Spain dances to the sound of water, and in the incessant discussion on territorial balance (we even have a ministry for the demographic challenge), these regions have huge potential as we move into 2024. Perhaps the future of these villages is to become the villages of the future.”

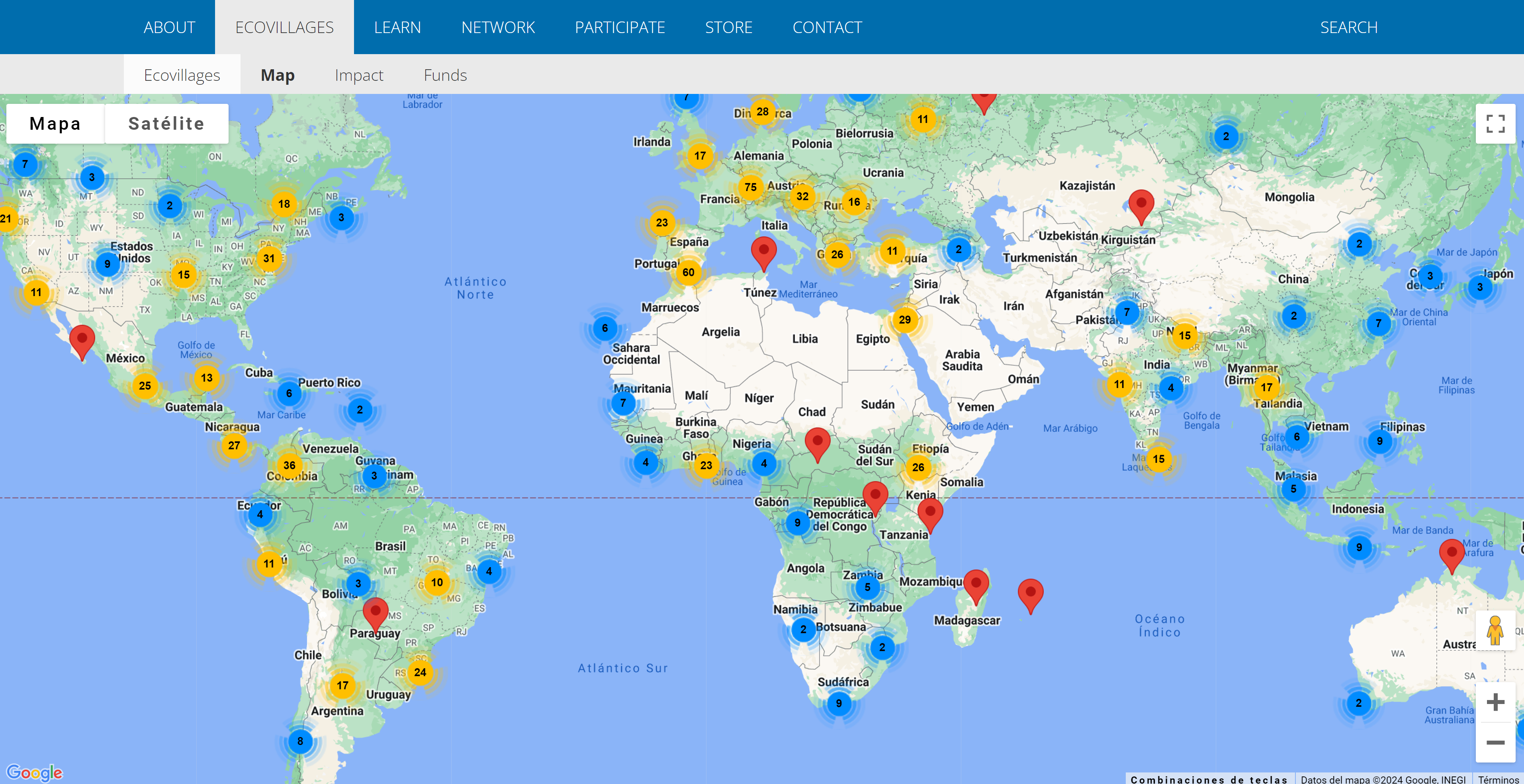

Map of ecological communities: Source: Ecovillage

The Colonization Villages symbolize the last great effort made by the Spanish State to once again unlock the value of the countryside from an integral perspective, and its continued existence without the threat of depopulation will be key to its success. We should re-examine this legacy model and modernize it to create modern ecovillages rooted in the bioeconomy, as well as a new circular way of life to be built with new materials such as cross-laminated timber (CLT).

There are some rural areas now emerging as vanguards of efficiency and regenerative living. The GEN – Global Ecovillage Network is a prime example of this progress, with its network demonstrating how communities can lead a sustainable future.

The intersection of 1970s counterculture and its flagship projects, such as the Earthships and The New Alchemists project on Cape Cod; and the ecology of the 1980s-90s has catalyzed resilient innovations such as Regen Villages. At the local level, there are projects such as the housing developed by Edra arquitectura km0 – Ángels Castellarnau Visús, which exemplify how the development of the rural environment and its communities can be regenerative from a global perspective and in terms of sustainability, focusing on comfort, energy efficiency, km0 bio-based materials and sustainable design. EDRA designs spaces and objects that are more natural, beautiful and comfortable and which blend into the environment. That is the definition of the New European Bauhaus.

THE TERRITORY AS A LABORATORY

Rural depopulation is a multi-scale challenge that requires a multidisciplinary and collaborative approach, as well as new tools such as artificial intelligence. The future of rural communities depends on our ability to integrate innovative solutions that respect and enhance the historical, cultural and natural heritage of these areas, opening a path towards sustainable and vibrant rural development.

Over the last few years we have been working toward various projects that all pursue a broader objective, namely Article 174 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU). The EU seeks to support regions suffering from severe and permanent natural or demographic handicaps, such as mountainous regions, sparsely populated areas, and islands by exploring infrastructure, promoting economic development and supporting job creation, among other measures. We propose a Territory as a Laboratory, a NEB Lab as a platform for social innovation and transformation of the territories. This multidimensional approach seeks to combine architecture and design, ecology, social innovation and the circular bioeconomy to foster transitional pathways to sustainable geographies and new ways of living. The initiative focuses on networks of domesticity, extending beyond conventional physical boundaries to promote trans-territorial co-development and mutual care.

Through hubs, living labs and territorial sandboxes, NEB Lab implements a multidisciplinary approach that fosters collaboration between citizens, scientists, creators, architects, politicians, inhabitants and entrepreneurs to co-create circular solutions within the bioeconomy of the sustainable management of their territories.

A hub will act as a meeting and collaboration point, bringing together numerous players to foster innovation and knowledge sharing. The living lab will provide a real-life environment where citizens and stakeholders can experiment and validate innovative solutions in everyday contexts, thus enabling user-centered research and development. Meanwhile, the territorial sandbox will provide a flexible regulatory framework, allowing for the experimentation of policies, techniques, materials, products, technologies and business models within a controlled environment, all with the aim of assessing their impact and feasibility before implementing them on a larger scale. NEB 174 Lab underscores the importance of sustainable land management. For example, it champions sustainable and integrated forest management, working alongside the entire forest value chain, from biomass and the creation of new pastures for extensive cattle grazing to the adaptation of innovative business models such as the SOLID® CLT product of Fustes Sebastiá. Brought together, these elements of the bioeconomy and innovation form a robust ecosystem to transform the way we live and reinvigorate depopulated territories in rural, mountainous and sparsely populated areas, exceeding and outperforming the colonization villages, while setting an example and providing a blueprint for the necessary changes to be made to cities. NEB 174 Lab aims to rebuild a symbiotic future between depopulated areas and cities, thus allowing us to accomplish the Sustainable Development Goals and land on earth.

Can we land on the Earth of our great-grandparents to sow a future where harmony with the planet brings us back to a common home and our lives become more fulfilling? Can we create a future in symbiotic harmony with nature, as we rediscover a common home for all?

Comments on this publication