Since time immemorial, humans have exploited the earth’s resources to extract materials for a variety of uses, but also for aesthetic reasons: gold, other precious metals or diamonds are part of the luxury industry, items for mere display or economic investment. But the environmental and climate costs of these materials lead us to question whether we should continue to pay such a high price for them if they don’t serve a necessary practical function. The same goes for gemstones. So when it comes to making a choice, a conscientious consumer might at least ask: are some more sustainable than others?

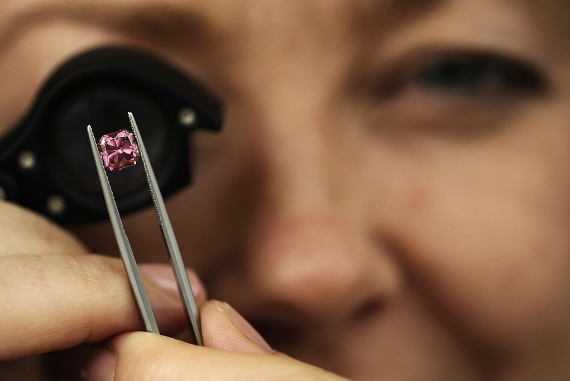

The term gemstone is very broad, although traditionally only diamonds, emeralds, rubies and sapphires are considered precious; the rest are semi-precious and cover a wide range of materials, including not only minerals or rocks, but also materials of organic origin such as pearls, jet (a type of coal) and amber (fossilised resin). In total, there are more than 100 types of gemstones, originating from more than 50 countries. The only thing they have in common, apart from their durability, is their aesthetic value, which explains their use in the manufacture of jewellery and other luxury items. Their name does not reflect their value either, as some stones that are not classically considered “precious” are very expensive due to their rarity.

One example is painite, discovered in Myanmar in 1957, which can fetch up to $60,000 per carat (0.2 grams), many times more than diamonds. Only three such stones were known before the turn of the century. And although recent mining has now yielded thousands more, their rarity lies not only in their lack of abundance, but also in their geology, as the zirconium and boron they contain do not normally occur together in nature.

The key to the problem: mining

In the case of the discovery of painite, as in many others, rivers transport and deposit sediments containing gemstones, which are then collected. But then comes mining, and this is where precious and semi-precious stones become an assault on the environment, often at great social cost. Unlike diamonds, the vast majority of gemstone mining—80%—is small-scale, artisanal mining in developing countries, often unregulated and uncontrolled.

Although experts often point out that gemstone mining is not as chemically polluting as metal mining, the damage is still undeniable. According to authors Jose Antonio Puppim de Oliveira and Saleem Ali, who have studied the Brazilian mining of emeralds—a beryllium cyclosilicate containing traces of chromium or vanadium that give them their green colour—and despite the fact that their extraction does not use toxic materials like mercury in gold mining, this activity causes “widespread deforestation, erosion of abandoned mines, and soil and water pollution in streams.” And while their price can exceed that of diamonds, even with low taxes to encourage the activity, the economic benefits remain at the top of the production chain; mining attracts immigration in search of work, but working and living conditions are miserable.

Similar problems exist in other parts of the world. In Madagascar, where illegal sapphire mining has absorbed tens of thousands of workers and become the second largest source of employment after agriculture, 90%of the forests that provide habitat for lemurs have been lost to deforestation, largely due to this activity. In Sri Lanka, one of the world’s major gemstone producers for at least 2,500 years, mining has caused “loss of fertility for agricultural activities, land use conflict, destruction of landscape, loss of soil and erosion of the soil, deforestation, destruction of fauna and flora,” according to researchers at the University of Sri Jayewardenepura.

Similar cases have been documented in a region of Kenya where tsavorite, a rare and precious variety of green garnet, is mined. This is compounded by social and humanitarian conflicts, as in the case of Burmese rubies, which have supported military dictatorships. Uncontrolled mining sometimes leads to landslides that claim human lives, as has happened on several occasions in Myanmar.

Synthetic and recycled gemstones

Overall, there does not seem to be a universal recommendation as to which stones are more sustainable than others; gemstones are an under-researched sector as a whole, so there is a lack of general data, which experts are trying to fill with new research. As with diamonds, the industry advocates ethical and sustainable sourcing, and some gemstone retailers claim to adhere to such sourcing and insist on traceability, so not all cases deserve the same judgement.

However, with 95% of jewellery’s carbon footprint concentrated in mining and only 5% in manufacturing, one alternative to reduce this impact is synthetic gemstones. The mining industry and gemstone laboratories are keen to defend the environmental costs of their respective activities, but it is generally accepted that synthetic stones reduce the water, energy and carbon footprint, with a lower price and no impact on ecosystems. But there are nuances: the manufacture of gemstones in the laboratory also consumes mined products, their constituent elements, and the difference in emissions between a lab-grown diamond powered by renewable energy and one powered by coal, as in India, can vary from 17 kg of CO2 per polished carat to as much as 260 kg per carat. Finally, another option is secondhand jewellery or recycled gemstones, a growing market.

Comments on this publication