A 2017 study estimated that about 8.3 billion tonnes of plastic have been produced since the end of the Second World War, when they started to become widespread. Of all the waste generated by these materials, 79% has ended up in nature. By 2050, the world’s natural areas will be home to 12 billion tonnes of plastic. Part of this problem is made visible to us through images of island paradises whose beaches are covered with garbage. But another part is invisible to the eye, the microplastics, pieces that are manufactured in millimetric or micrometric size, or fragments that result from the degradation of objects used in everyday life.

Microplastics are already so ubiquitous on our planet that there are no places free of this pollution, which is even transported by the air. A recent study found that parks and nature reserves in the western United States receive a constant rain of plastic at a rate of about 132 fragments per square metre per day, adding up to more than 1,000 tonnes per year in these protected areas. “My study also showed that airborne plastics are within the respirable range so there are potential impacts to humans as well,” study director Janice Brahney of Utah State University told OpenMind. Other research has also found this “plastic rain” in other theoretically pristine places, such as remote corners of the Pyrenees or the snows of the Arctic; of course, there is shortage of it in our cities either.

The “plastic soup” in the Mediterranean

A large proportion of the planet’s microplastics end up in what are, par excellence, the ultimate sinks for human waste: the oceans. The problem of microplastic pollution began to attract public attention with the discovery of the large island of garbage in the Pacific and similar oceanic enclaves where marine currents form vortices that concentrate immense amounts of this pollution.

However, contrary to popular belief, “there are no floating islands in the ocean,” Stefano Aliani, from the Italian Institute of Marine Sciences, told OpenMind. The size of the fragments does not make them visible to the naked eye, even from a boat sailing through these areas. In 2016 Aliani led a major study to identify the ingredients of the “plastic soup” —as the researcher prefers to call it— in the Mediterranean, one of the marine regions of the planet most affected by this pollution. The two most abundant compounds were no surprise, polyethylene and polypropylene, the most common commercial plastics, typically used in packaging and bags.

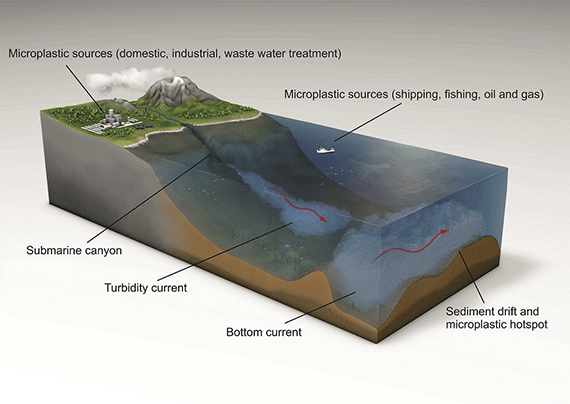

Also contrary to what might be imagined, the buoyancy of plastics does not restrict this pollution to the surface; in fact, only 1% of all these materials entering the oceans is found in this surface soup. In recent years, research such as that led by the University of Barcelona (UB) in the Mediterranean has discovered the presence of large quantities of microplastics on the seabed, in many cases textile fibres —of which more than 60 million tonnes were manufactured in 2016— and their transport by the currents at the bottom, where they settle to form aggregates.

Currents, plastics and foci of marine biodiversity

But while microplastic pollution of the seafloor is already a known fact, how it gets there is less so. “The dynamics of microplastics have not been identified at all,” Anna Sánchez-Vidal, co-director of the research at UB, told OpenMind. “Marine dynamics are very complex and variable in space and time,” says the researcher. One of the features of this dynamic is that it creates hotspots where microplastics tend to accumulate, forming islands at the bottom, as invisible as the surface ones. “A few years ago, we saw this in the Mediterranean trenches, and that they were also capable of pulling in other contaminants,” Marinella Farré, researcher at CSIC, told OpenMind.

The discovery that other components are also accumulating in the same areas has worrying implications. A recent European study reveals that the same currents that carry microplastics to these hotspots also bring nutrients and oxygen there, so the most polluted places are actually foci of marine biodiversity. However, “further studies in other deep-sea sedimentary systems are necessary to better understand the distribution of plastics on the ocean floor,” study co-director Florian Pohl at Durham University told OpenMind.

In fact, there are still so many unknowns about microplastic contamination that even its environmental impacts are not known exactly. “Pollution is absolutely harmful, there is no scientific doubt about it,” says Sánchez-Vidal. “We already know the negative effects of plastics on large marine animals: suffocation, entanglement, drowning.”

A debate on toxicity

But when it comes to microplastics, there still doesn’t seem to be a clear consensus. Voices such as that of environmental toxicologist G. Allen Burton at the University of Michigan have repeatedly insisted that the “primary plastic risk in aquatic ecosystems is macroplastics.” As for microplastics, for marine biologist Rick Stafford at Bournemouth University, “at the moment, there is very little evidence that it has major effects on wildlife populations; ingestion is known to kill individual animals, but isn’t really effecting things like reproduction rates of populations,” he told OpenMind. “Has the microplastic problem been overstated? The simple answer is nobody knows,” ecologist Matthias C. Rillig at the Free University of Berlin, who studies microplastics in terrestrial ecosystems, sums up for OpenMind.

Yet, while understanding the physical action of microplastics on wildlife may be attainable, the discrepancy increases when it comes to assessing the toxicity of the chemical compounds that these materials can release into the environment. Researchers like Sánchez-Vidal argue that the organic contaminants and additives used in plastics have a great impact on the health of species. On the contrary, for Stafford, “the discussions on the toxicity of plastic don’t really hold up to scientific evidence.” It is not even known whether certain plastics might be particularly toxic. According to Aliani, “there is no evidence that one polymer is more dangerous than others in terms of toxicity. There are many studies ongoing and soon there will be more answers.” “I don’t think we know enough about the potential consequences of microplastics in the environment,” concludes Brahney.

In any case, the above does not challenge the urgent goal of reducing our consumption of plastic, especially considering that, as Sanchez Vidal points out, “even if we stopped producing plastic today, its presence will continue to increase exponentially because of the quantity that is already in the marine environment and is being fragmented.” As Stafford says, “we should certainly try to stop putting plastic into the oceans, and governments need to legislate urgently to do this.” But he warns that “plastic isn’t the biggest threat to the seas. Overfishing and climate change are much more important.”

Comments on this publication