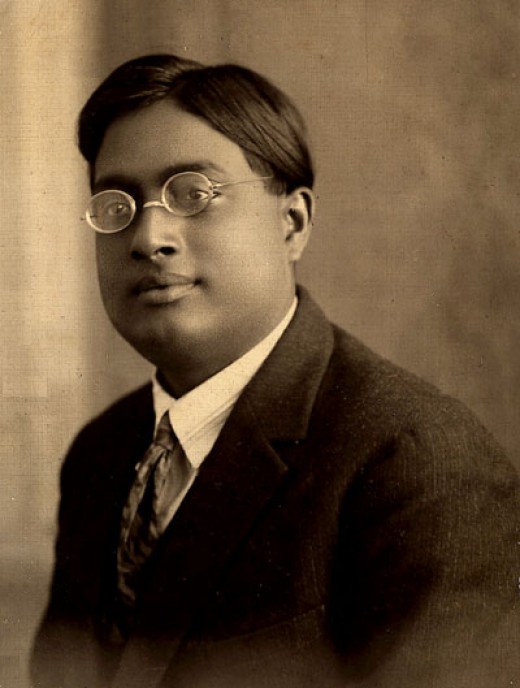

The physicist Satyendra Nath Bose managed to find his way into the firmament of great researchers like Einstein, Bohr and Schrödinger, thanks to his talent and despite working from India, far from the major European capitals of science

Marie Curie wouldn’t stop talking. She was explaining that, not long before, she had had another collaborator from India and the experience had not borne much fruit because that physicist did not speak French well enough. “You will need to spend at least four months studying French if you want to enter my lab,” explained Curie in a conversation in English. Satyendra Nath Bose nodded back, not daring to interrupt the legendary researcher who back then was a legend (and who had already collected two Nobel prizes). The interview was a disaster. Bose, who had come to Europe from the University of Dhaka to imbibe the best work that was being done in that golden age of physics, did not dare interrupt Curie for even an instant to say that he spoke French perfectly after having studied it for ten years.

That calamitous examination took place in Paris in 1924, now 90 years ago. In those days Bose was able to meet some of the most brilliant physicists and mathematicians in history, such as Max Born, Louis-Victor de Broglie, Paul Langevin and Albert Einstein, and through them Niels Bohr, Werner Heisenberg and Erwin Schrödinger. Much later, in 1972, a journalist who interviewed Bose noted that, even then, when the physicist already formed part of the Royal Society of London, “he continued to feel terribly intimidated by the Europeans.”

These anecdotes illustrate the humility of one of the most commonly underrated physicist in history, Satyendra Nath Bose Bengali, the anniversary of whose death in his native Calcutta four decades ago has just passed. Yet his name has been on the lips of many people as never before: hundreds of millions of people unknowingly name him when talking about the Higgs boson. The first part of the name acknowledges Nobel Prize in Physics winner Peter Higgs, but the other part, boson, describing the class of particles, was coined by fellow Nobel laureate Paul Dirac to recognize the transcendental contribution of Bose, the shy Indian who never felt comfortable among Europeans.

This great achievement of Bose almost didn’t become known. In late 1923 the Bengali sent his work on particle physics to the British journal Philosophical Magazine, a reference publication in which had been published, for example, some of the great ideas of Niels Bohr. Six months later, the publishers notified him that they had rejected his work for publication. For once, Bose dared to bang his fist on the table of the history of physics and sent his work directly to Albert Einstein. At the time, Einstein was not only the best-known physicist, but was also one of the most famous personalities on the planet. Bose wrote to him decisively, but with great modesty.

“Dear Sir, I have ventured to send you the accompanying article for your perusal and opinion. I’m anxious to know what you think of it,” began the letter, accompanied by his study of just four pages. “I do not know enough German to translate the document. If you think it is worth it, I would appreciate that you have it published in the Zeitschrift für Physik. Although I am a complete stranger to you, I feel no hesitation in making such a request.” It wasn’t the first time he had written Einstein; some few years earlier he had asked permission to translate and publish his major works in India.

Einstein not only translated, but he also endorsed the work of Bose with whom he collaborated to develop the ideas that the talent of the Bengali revealed in his statistical methods. Today, this type of telework among researchers is very common, but it should be remembered that in 1924 and1925 there were no documents in the cloud, nor video chats, nor even the ability to communicate instantly via email. However, the work prospered and led to the description of a new state of matter called Bose-Einstein condensate (BEC).

At this point, another striking parallelism with Higgs comes to light: the ideas of the Briton were proved true thanks to the LHC almost half a century after they were theorized, which earned him the Nobel Prize in Physics, shared with his fellow discoverers at CERN. The work of Bose, describing a concentration of particles in a compact space at ultralow temperatures, forming a kind of superparticle, was successfully reproduced in 1995, 70 years after the Bengali described it. In 2001, Eric Cornell, Wolfgang Ketterle and Carl Wieman, would be awarded a Nobel for proving that Bose was, like Higgs, correct. But the man from Calcutta had been dead for decades.

The publication of his work with Einstein granted Bose safe passage; the authorities unblocked his request and he was able to go to Europe for two years, to Paris and Berlin, the places where every day a new page in the history of modern physics was being written. “Everyone (all the physicists) in Berlin seems quite excited about the way things have evolved in physics,” wrote Bose from the German capital to a friend. “Everyone is very disconcerted and very soon we will see a new debate on the study of Schrödinger. Einstein seems very enthusiastic about it. The other day, coming from the symposium, we met each other jumping into the same railway coach, and he immediately began to talk excitedly about what we had just heard. He admits that it looks like a huge issue, considering the many things that these new theories correlate and explain, but he is also very worried. All of us were silent and he talked almost all the time, unaware of the interest and excitement that was awakening in the minds of the other passengers.”

But instead of staying in the Old Continent to enjoy this exciting environment, Bose returned to India, to the universities of Dhaka and Calcutta, to become a teacher and to try to improve a country as young as ancient and as big as poor. Recognized as one of the founding fathers, a friend of Nehru, he played a crucial role in the development of education in India, especially for women, and the access to culture. His formulas, the Bose-Einstein statistics, laid the foundation for many other physicists to reach the Nobel Prize throughout the twentieth century. Yet when asked if he missed that award, he replied: “I have all the recognition I deserve.” He had a great talent for physics, but would rather be in front of blackboard teaching his students, playing the flute and the esraj, getting together with friends, enjoying the gastronomy.

The vocation of Bose was to encourage his people in their struggle for knowledge and freedom, against ignorance and hatred, creating a free and enlightened India which made him a legendary figure in his country, almost as well known as Tagore or Gandhi. When the Bengali physicist died in February 1974, half a century after his greatest discovery, hundreds of thousands of people filled the streets of Calcutta in the funeral procession. Most attendees did not know anything about the Bose- Einstein and had never heard of bosons, but they offered their sincere appreciation.

You can read more about Nath Bose and other great physicists in this article by Ramamurti Shankar.

Ventana al Conocimiento (Window Knowledge)

Comments on this publication