The anniversary of the theory of evolution is usually celebrated on November 24, the day on which Darwin published his book “The Origin of the Species” (1859). However, this view of history leaves out an even more important date for understanding how the theory of evolution was conceived. On July 1, 1858, at the Linnean Society of London, a summary of a theory of natural selection was presented. The authors were Charles Darwin and Alfred Russel Wallace, and they used this theory to explain the evolution of the species. Modern biology and evolutionism were born on that day.

Evolution was not a brilliant and solitary brainstorm of Darwin. The idea had spent almost a century floating about in the scientific ether. Linnaeus, Lamarck, Erasmus Darwin (Charles’ grandfather) and other great scientists had theorized about what was then called the transmutation of species. But Victorian society rejected this and other revolutionary ideas that suggested non-theological explanations for the placement of the continents, the nature of human intellect or the origins of life itself.

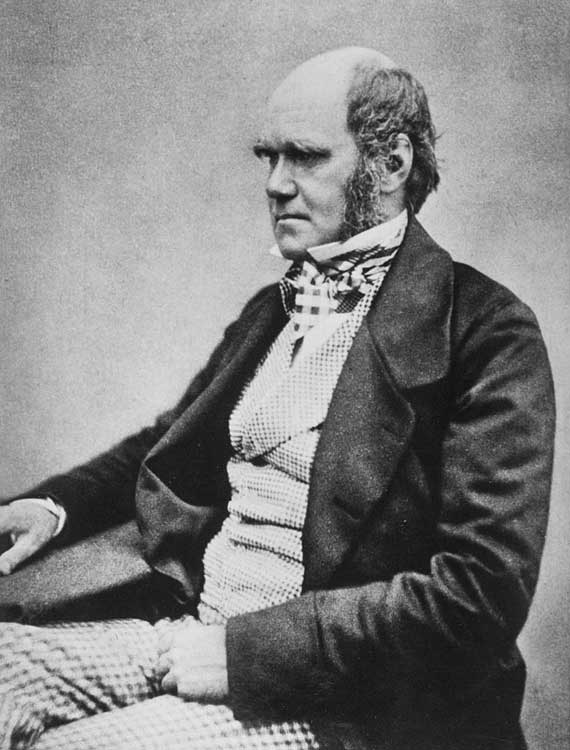

At the conclusion of his famous voyage on the Beagle, in October 1836, young Charles Darwin (12 February 1809 – 19 April 1882) was welcomed by this Victorian scientific elite. By then his theory of evolution was already quite clear, and he knew that it would raise people’s hackles. This fear was one of the keys that delayed the publication of the theory. It took over 20 years until, in June 1858, an already mature Darwin received a letter from Alfred Russel Wallace (8 January 1823 – 7 November 1913). This young man, who was in the middle of a naturalist expedition in the Malay Archipelago, had independently arrived to the same conclusion: natural selection was the mechanism that determines the adaptation and speciation of living beings, regardless of divine influence. A humble and almost naïve Wallace then wrote to Darwin to ask for his opinion and, if Darwin felt it appropriate, to send a summary of his ideas to the eminent geologist Charles Lyell.

Darwin, thus far reluctant to publish his theory, decided then to do so. He and his circle of selected scientists organized a joint document to be read at the next meeting of the Linnean Society, although neither of the men could attend. Wallace was still in Malaysia and Darwin was in mourning over the death only three days earlier of his infant son of 19 months.

That day marks a before and after in the history of biology. But the joint article of Darwin and Wallace did not cause much of an immediate sensation. Wallace himself only learned about it much later, when “The Origin of Species” had already been published and the expected scandal had broken loose. But far from considering that the most famous and veteran naturalist had appropriated his idea, Wallace was one of the great defenders of Darwin’s ideas. So much so that in the 1930s, when the ideas of evolution reappeared with the force that they possess today, “Darwinism” (1889), written by Wallace himself, was the most recent and complete version written on evolutionism and the reference work.

The circumstances of the epoch and the personal idiosyncrasies of each of the men ensured that, while Darwin would triumphantly go down in history, in contrast, the name of Alfred Russel Wallace would not appear in primary school books, nor would he have streets, parks or squares named after him. Not, at least, until today.

It is very well known how Charles Darwin came up with the idea of natural selection after examining the different species of finches on the Galapagos Islands, collected on one leg of the Beagle voyage. Here we revindicate Wallace, recounting how he got to the same idea on his own:

Under the guise of collecting specimens for collectors in England, Wallace spent eight years in what would be one of the major voyages of discovery of the nineteenth century. First, he noticed the strange Asian subspecies of the westernmost islands of the Malay Archipelago; then he noted their absence on the eastern islands, where, however, strange species of Australian origin appeared. From this he deduced that there existed two families of animals belonging to two distinct continents separated by oceanic trenches (the so-called Wallace Line) that were, in fact, at one time joined to what are now hundreds of isolated islands. He also concluded that this isolation had led to the differentiation of the species. And, given the immense quantity of species he cataloged, he observed a continuity between all of them, a kinship so to speak. He thus deduced not only a theory of evolution, but also the mechanisms and effects that govern it and, what’s more, he framed it within a new understanding of geography: Wallace is the father of biogeography. And that is something that no one would dispute.

Comments on this publication