The character of the British physician Thomas Young (13 June 1773 – 10 May 1829) can almost be summed up in a couple of anecdotes that open and close respectively the career of one of the most prolific polymaths in history. When in his youth he began taking dance classes, his classmates found him tracing with a ruler and compass a mathematical diagram of the movements of the minuet, in order to improve them. And three years before his death, after having been hired as an expert by the insurance company Palladium, he sent a study to the Royal Society in which he explained a very complicated formula to calculate the value of the decrease in human life, to be used to calculate the size of the annuities of the insurance policies.

Thus, it is not surprising that, when author Andrew Robinson tackled the complex task of reviewing the life and work of Young in his book The Last Man Who Knew Everything (Plume, 2007), he warned in his introduction that his goal was simply to introduce the figure to those who did not know him, and not to draw a comprehensive biography. This was a difficult task when dealing with someone who had, before reaching the age of four, already read the Bible twice from beginning to end.

At age 14, Young was translating passages from the Bible into 13 languages, including Chaldean, Samaritan, Syriac and Ethiopian. He invented a new universal phonetic alphabet. Comparing 400 languages, he defined the Indo-European languages. He studied the mechanism of vision, discovered astigmatism and proposed that the retina sees in three colours—something that was confirmed a century and a half later. He developed what is now known as Young temperament (a method of tuning musical instruments), Young’s modulus (in elasticity), the Young-Laplace and Young-Dupré equations (in fluid mechanics) and Young’s rule (to calculate the infant dose of a drug). His articles for the Encyclopaedia Britannica covered 20 fields of knowledge and he even proposed a technique to improve the joints in carpentry.

All this, without going into what was really his profession, medicine, which curiously never stood out too much (said to be due to his strained relationships with colleagues, who did not approve very much of his dispersion of interests: Young just knew too much), and also discounting two of his contributions that deserve special mention.

His main finding

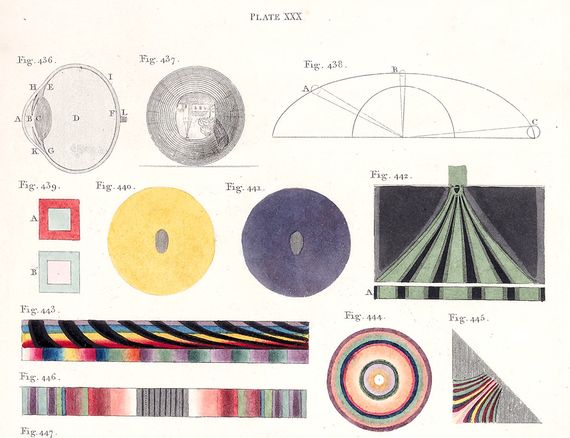

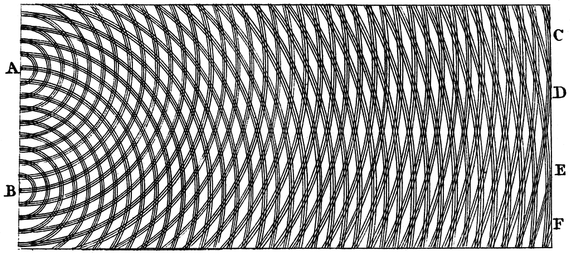

The first one was, according to Young himself, his main finding. In his time, the name of Isaac Newton was as admired and respected as it is today, and the master of physics had certified that light was composed of jets of particles, in contrast to the wave theory that circulated at the time. Few dared to question Newton’s word, but that was not the case for Young. In spite of being more of a thinker than an experimentalist, in 1803 he showed how a ray of light split in two produced a pattern of light and dark bands, corresponding to the places where the waves added together or cancelled out and vanished.

Young’s interference experiment—also called the double slit experiment—as simple as it was powerful, laid the foundations for the understanding of the double nature of light as a wave and a particle at the beginning of the 20th century. For physicist Richard Feynman, this phenomenon contained the heart of all quantum mechanics and its unique mystery.

The hieroglyphics of the Rosetta stone

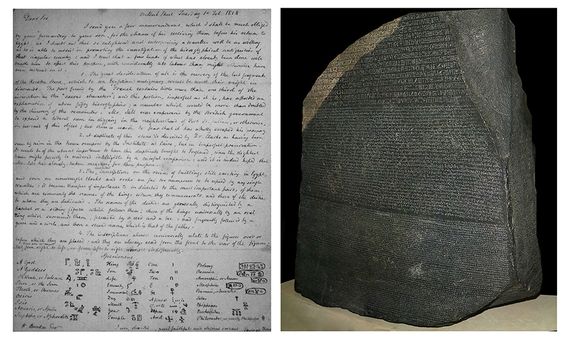

The second mention is for one of Young’s oft-forgotten contributions. In 1822, the Frenchman Jean-François Champollion deciphered the Egyptian hieroglyphics of the Rosetta stone, a stele found in 1799 by Napoleonic soldiers in Egypt and showing the same text in three different languages. But by 1814 Young had already tackled the same goal and made remarkable progress, though without reaching the final success of Champollion.

The bitter rivalry between the two men was then translated into a clash of nationalisms that has lasted until today. According to Richard Parkinson, the former curator of the Egyptian collection of the British Museum that houses the stone, French visitors used to complain that the portrait of Champollion in the museum was smaller than Young’s. The curious thing is that the British protested just the opposite.

Comments on this publication