The previous evening, Ota Benga had danced and sung around the ceremonial fire. In the early hours of March 20, 1916, he locked himself in a shed next to his house, retrieved a gun he had hidden there and shot himself in the heart.

Although Ota Benga was a Congolese pygmy, the event did not take place in Africa, but in the United States —the country where the man had been exhibited as an attraction, first in the Louisiana Purchase Exposition (Missouri) in 1904, and then in 1906 in the Monkey House at the Bronx Zoo (New York). It was a thankless life that he decided to end at are 32.

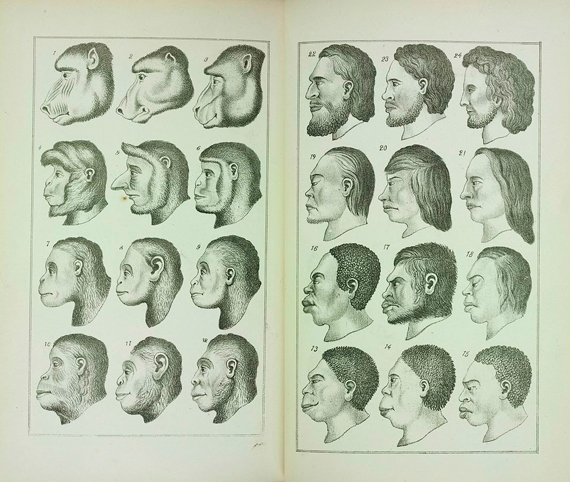

The case of Ota Benga is one of the most notorious —out of many throughout history— where human beings have been exposed to the public like animals. In the nineteenth century, the new colonialism and the emerging science of anthropology took this kind of exhibition from circuses and traveling fairs to the more formal environments of museums and zoos. Anthropology then considered that “races” different to the white one were intermediate stages of human evolution.

Interestingly, those who defended this position were believed to be forward thinking, as their ideas found shelter in the common origin of humans and apes postulated by Darwinism to construct a hierarchy of superior and inferior races. The truth is that Charles Darwin‘s approach to human races could be hoisted as a flag to support racism. Although the British naturalist was a staunch supporter of the abolition of slavery and proposed a common evolutionary origin for a single human species, in his writings he spoke of civilized races as opposed to other wild ones, and he considered Africans or Australians closer to apes than to Caucasians.

Thus, the public display of Ota Benga had the support of some prominent scientists of the time and even enjoyed the backing of the mayor of New York. In those days, an editorial in The New York Times said, “The idea that men are all much alike except as they have had or lacked opportunities for getting an education out of books is now far out of date.” On the contrary, the opposition movement was led by anti-Darwinian African American clergy, who declared that “the Darwinian theory is absolutely opposed to Christianity, and a public demonstration in its favor should not be permitted.”

The concept of human race has one biological interpretation and another cultural one, something that Darwin’s contemporaries did not recognize. A century after the suicide of Ota Benga, and although racial conflicts have not disappeared, it is undeniable that the view of race as a cultural term has evolved in society. For anthropologist Jonathan Marks, of the University of North Carolina in Charlotte (USA), this change in perspective has been “a two-step process,” he tells OpenMind.

“Up to World War I there was still a general feeling that non-northern-Europeans were inferior kinds of beings by nature, or biology,” explains Marks. According to the anthropologist, the idea then began to spread that the problem was not biological but cultural, which gave birth to a scientific conception of culture. “It was assumed that northern-Europeans were equivalent biologically, but had instead more (or better) culture.” However, says Marks, the second step was that it was confirmed that the most technologically advanced nations could also be the most barbarous.

An example often cited by historians is the Mau-Mau rebellion that led to Kenya’s independence. The movement was born of those Africans recruited by Britain to fight in World War II. During the battles in the jungles of Asia, the soldiers realized that the British were no better or superior to them, fueling nationalistic pride and the longing for equality. Thus, by the mid-twentieth century, summarizes Marks, it was understood that “different peoples had different cultures, not better.”

But if the cultural concept of race crumbles, for many biologists it is also untenable as a scientific category because it does not reflect human genetic diversity. “Phylogenetic and population genetic methods do not support a priori classifications of race, as expected for an interbreeding species like Homo sapiens,” wrote a group of experts from two US universities and the Museum of Natural History in the journal Science last February.

The authors advocated doing away with the concept of race in human genetic research, “problematic at best and harmful at worst,” and replacing it with the concept of geographical ancestry or populations, more suited to the heterogeneous reality of the human species. This, they added, would also serve to send an important message to society, that the use of “race” should remain confined to addressing the social problems of racism and, if anything, its biological effects, such as those differences that affect health. A necessary proposal, but for Marks it is too optimistic. “Right now the biggest problem is making sure that the scientists themselves understand race, and a lot of them don’t.”

Comments on this publication