It may still seem like a science fiction weapon, but laser technology is a product of quantum physics, both sophisticated and ordinary due to its everyday use: it can be found in supermarket checkout scanners, CD and DVD players, and in surgical operations to correct nearsightedness. Its theoretical basis was set by Einstein, but the path from theory to practice was not straightforward: decades went by before a cluster of scientific and military successes, blunders, collaborations and rivalries made laser technology a reality

The maser (or microwave laser), the first device of its kind, was patented on 24 March, 1959, by Charles Townes and Arthur Schawlow, despite the fact that their company saw no clear practical application for this invention. The idea to amplify waves of the same frequency (wavelength) was stated by Albert Einstein Einstein in two papers published in 1916. However, its practical realization -with all the new theoretical and experimental elements this entailed- came in the 1950s. Those responsible for this achievement were, independently, the Soviet physicists Nikolai Basov and Aleksandr Prokhorov and U.S. physicist Charles Townes (July 28, 1915 – January 27, 2015). Nevertheless, regardless of who came first and the antagonism between the two Cold War superpowers, all three shared the recognition by being awarded the Nobel Prize for Physics in 1964).

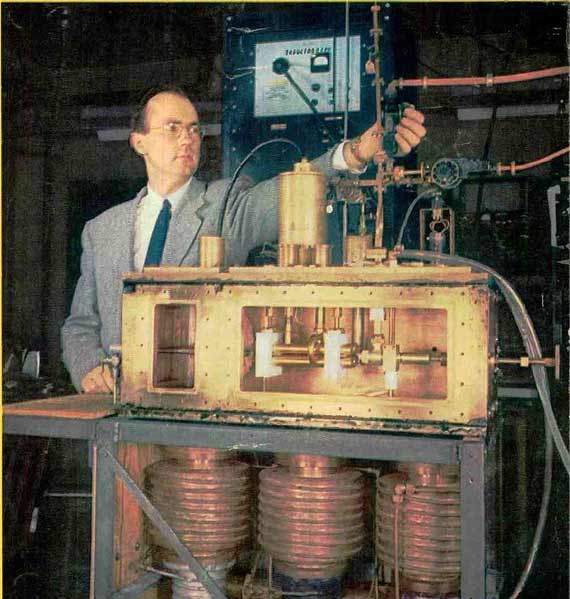

In May 1952, during a conference on radio spectroscopy at the USSR Academy of Sciences, Basov and Prokhorov described the maser principle, although they did not publish anything until two years later (Basov and Prokhorov, 1954). They not only described their principle, but Basov also built one as part of his doctoral thesis, a few months after Townes did so himself.

It is worth summarizing how Townes –separately- got to the same idea of the maser, as it illustrates the diverse elements that can form part of the processes of scientific discovery. After working at Bell Labs between 1939 and 1947, where his responsibilities included -among others- research related to radar technology, Townes moved to the Radiation Laboratory at the University of Columbia, created during World War II with the aim of building radars, which were eventually essential for the unfolding of the war.

As in the case of other institutions, this laboratory continued receiving money from the military after the war, devoting 80% of its budget to the development of microwave generating tubes. In the spring of 1950, Townes organized -at Columbia- an advisory committee for the Office of Naval Research to assess new ways of generating microwaves smaller than one centimeter. After one year of working on this issue, he came up with a new approach before attending one of his committee’s sessions: the idea of the maser. When he succeeded in 1954 -in collaboration with a young PhD, Herbert J. Zeiger, and PhD James P. Gordon- in making this idea operational by using a gas with ammonia molecules, it emerged that the oscillations produced by the maser were characterized not only for their high frequency and power, but also for their uniformity. The maser, in effect, produces a coherent microwave emission; that is, highly concentrated single wavelength radiation

Even before masers started to proliferate, some physicists began trying to extend this idea to other wavelengths. Among them was Townes himself (and also Basov and Prokhorov), who in the autumn of 1957 began his work that went from microwaves to visible light, collaborating with his brother in law, Arthur Schawlow, a physicist at Bell Labs. The result of their efforts was a fundamental paper, where they showed how to build a laser, which they still called «optical maser». It is worth mentioning that the lawyers at Bell Labs, for whom Schawlow worked and who had hired Townes as a consultant, thought that the idea of the laser was not interesting enough to be patented; they only did so at the insistence of Townes.

Find out more about the revolution in physics in the second half of the twentieth century in this essay by José Manuel Sánchez Ron “The world after the revolution”.

Comments on this publication