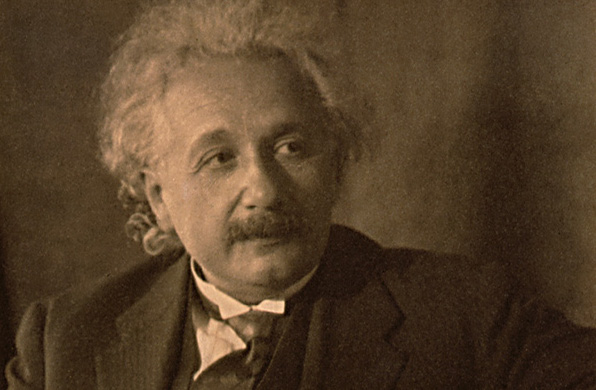

If there is one scientist that almost anyone on the street could name, it is certainly Albert Einstein. As Jürgen Neffe recounted in his biography, Einstein was the first mass media scientist in history, promoted to the status of idol when the London newspaper The Times reported in 1919 that the theory of general relativity had been demonstrated by photographs of an eclipse of the Sun that revealed the curvature of the light of the stars, as the physicist had predicted.

Einstein received the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1921. But although his name has been mythically linked to his theory of relativity and his famous equation E = mc2, it was not this achievement that earned him the prize, but rather his explanation of the photoelectric effect, a phenomenon that Heinrich Hertz had observed in 1887. In 1905, Einstein described the mechanism by which light, when shone onto a metal surface, caused the ejection of discrete packages of energy, or quanta. The idea of the quanta of light gave birth to a scientific revolution, which in the first decades of the twentieth century would give rise to the development of quantum physics.

Despite opening the way to a new physics, Einstein maintained a strange relationship of suspicion toward the views held by those leading this vibrant new field of science. Physicists such as Heisenberg or Schrödinger introduced with ease concepts that deviated from realism, such as that the actions of the observer determined the properties of the system, or that an atom could be intact and disintegrated at the same time (or that a cat could be alive and dead at the same time, as in Schrödinger’s most famous metaphorical example).

“God does not play dice”

But for Einstein, this dependence on probability suggested rather a lack of awareness of the laws involved in the governance of reality. “I am convinced that He [God] does not play dice,” he wrote in a letter to fellow physicist Max Born. On another occasion he asked his biographer Abraham Pais if he believed that the moon only existed when they looked at it.

In 1935, Einstein published, together with his colleagues Boris Podolsky and Nathan Rosen, a mental experiment that today we know as the EPR paradox. There exists the possibility that two particles share their properties, as if they were twins. But if, as the predominant school of thought on quantum physics defended, the action of an observer on one of them must influence the other, this would imply that there was an instantaneous communication between the two. This, argued Einstein and his collaborators, would break the unbreakable limit of the speed of light. There must therefore exist “hidden variables” according to which the system obeyed a sort of previous programming.

In conclusion, quantum physics was not wrong, Einstein thought, it was simply incomplete. Just as general relativity had described a fabric of space-time that bound bodies together, eliminating the need for a gravitational action at a distance that had troubled Isaac Newton himself, Einstein believed that these hidden variables in the local environment of the particles before their separation would explain their later behaviour without resorting to what he called “spooky action at a distance.”

Discussions for decades

The EPR paradox fuelled lively discussions among physicists for decades, but it was in 1964 that the Northern Irish physicist John Stewart Bell ruled out the existence of hidden variables that could explain what we now know as quantum entanglement. As a consequence of Bell’s theorem, it was concluded that there was a non-local action at a distance between the particles.

However, Bell’s statement did not settle the debate. In later years, other physicists have endeavoured to close the possible cracks (or loopholes) of quantum entanglement experiments that could open a path for other explanations within the realist view of Einstein. For example, critics argue that experiments may be vitiated by errors in the instrumentation or by biases of the researchers.

Among those physicists who have tried to shield quantum entanglement experiments against any possible loopholes is Ronald Hanson of the Delft University of Technology (The Netherlands). “The loophole-free tests of 2015, of which ours was the first, have closed all loopholes that can be closed,” Hanson tells OpenMind. “Does this prove the existence of entanglement? I would rather put it the other way round: the worldview of local causality, or local realism, has been proven false,” says Hanson.

In favour of quantum entanglement

But there are still those who argue that the short time that elapses between the generation of the particles and their measurement in the entanglement experiments could continue to support the idea of programming. A recent experiment has tried to get rid of this possible loophole by measuring photons from stars up to 600 light-years away. It is highly unlikely, say the researchers, that the programming of particles could last for 600 years. However, for Hanson these so-called “cosmic” experiments of Bell do not provide a fundamental advance, since they do not rule out the influence of hidden variables.

According to David Kaiser, a physicist at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and co-author of the latter study, “it is still a bit too early to proclaim that quantum entanglement has been “definitely proven.” The reason, says Kaiser, is that the latest experiments until now have closed the loopholes two at a time, but not all three at the same time. “But the recent progress in the field looks more compelling, in favour of quantum entanglement, than ever.”

Does this mean that the great Einstein finally failed in his mistrust of the quantum? Whether the current experiments would have made him change his mind or not, “who can say?” concludes Kaiser. “My view is that Einstein was one of the first to discover the non-local consequences of quantum theory. He did not believe those consequences could be true.” If he had had the opportunity to witness the latest developments, Hanson continues, “he would have accepted these as facts of nature; he was a very smart man!”

Comments on this publication