Heavy industry requires high temperatures for its processes, a need that cannot be met by electrification. Thermal bricks can provide an agile and immediate solution for decarbonised heat today, while waiting for technologies such as green hydrogen to mature and become competitive and scalable.

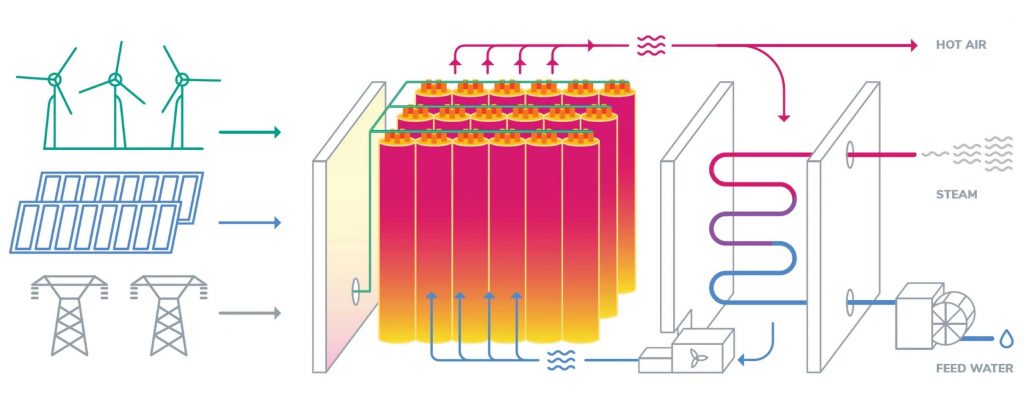

Imagine a humble brick heated like a piece of toast by a heating element that converts electricity from renewable sources into heat, but with much more power than a typical toaster. And now, to push the imagery further, let’s put a big pile of these hot toasted bricks into a steel container that can keep them hot for hours, even days; but watch out, because the temperature inside can exceed 1,500 °C. When the time comes to make use of all that blistering heat, fans blow air through the bricks, directing it at nearly 1,000 °C to where it is needed.

Well, these thermal batteries do exist. Developed by Californian startup Rondo Energy, they have an estimated lifespan of 50 years and require about four hours of charging (from electricity generated by wind or solar panels) to provide constant heat on demand, day and night. They can be used to make cement or steel, convert heat into steam or help control the temperature of reactors. A commercial prototype is already in operation at the Calgren Renewable Fuels plant in Pixley, California, which produces ethanol, biodiesel and RNG (renewable natural gas).

An alternative solution for heavy industry

The Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) presents this technology as The hottest new climate technology is bricks, offering it as an ingeniously simple solution to the needs of heavy industry, which requires high temperatures for its processes and is dependent on fossil fuels such as natural gas, because clean energy such as solar or wind power cannot be generated continuously.

“This sector, unlike others such as the residential sector, presents greater challenges for its electrification, which is the most efficient way to decarbonise and should be prioritised in order to achieve the goals of limiting the global temperature rise in to 1.5 °C,” says María Manzano, energy analyst at the Renewables Foundation, a think tank focused on the development of the renewable energy sector in Spain. “The main reason why electrification is more difficult is because of the high temperature requirements of some activities, such as metallurgy or ceramics. In some processes, 1,500 °C can easily be reached and exceeded. When the thermal jump is that high, electrification means a big loss of efficiency,” she says.

Although global emissions from industry fell by 1.7% to 9.2 Gt in 2022, according to the latest report from the International Energy Agency (IEA), it is still responsible for about a quarter of the CO2 we humans release into the atmosphere. “The largest absolute sectoral increase in emissions in 2022 was from electricity and heat generation. Electricity and heat sector emissions increased by 1.8% (or 261 Mt), reaching an all-time high of 14.6 Gt. Gas-to-coal switching in many regions was the main driver of this growth: CO2 from coal-fired power generation grew by 2.1%, led by increases in Asian emerging market and developing economies,” the research notes.

According to data from the international body, heat is the world’s largest energy end-use, accounting for almost half of total consumption in 2021, well ahead of electricity (20%) and transport (30%). Industrial processes are responsible for 51% of this total energy use, it adds.

Bricks to harness surplus clean energy

Rondo Energy’s thermal battery is significant because it is so advanced, but the fact is that universities and companies around the world are working on systems to capture the heat generated by clean energy and store it in bricks or other materials. For example, Antora Energy, also based in California, has introduced its own system using carbon blocks. These two systems, and others under development that use different materials and engineering, all promote their thermal batteries as a way to electrify industry, albeit indirectly, and to take advantage of excess renewable electricity generation (when energy is cheaper) and convert it into heat.

It is an accelerator for renewables, and a short-term solution that is available today, scalable and competitively priced, says John O’Donnell, founder and CEO of Rondo Energy, in a podcast on The Wharton Current on decarbonising industrial heat. “The first problem is economic, the second is temperature,” he says. He points out that other very promising technologies for providing decarbonised heat to industry, such as green hydrogen (a solution that Manzano supports as long as it is generated within the plant or industrial complex itself to avoid leaks, which result in energy loss), are currently expensive, inefficient and “not affordable” because they are not yet mature enough.

“Green hydrogen could scale up and become cost-effective within the next decade,” says the consultancy McKinsey, which has analysed the path to zero net emissions for nine key sectors. The steel industry in particular is paradigmatic because of its monstrous demand for heat.

Conner Gordon, marketing director at Rondo Energy, argues by email that its heat battery has cost and efficiency advantages over green hydrogen. “You can get the same heat at twice the efficiency and half the cost,” he says. There are also upsides in terms of availability and scalability. “We don’t use rare earth minerals; our system is made of common refractory bricks, available on all continents, and with no supply constraints,” he says.

These arguments make this innovation an attractive option for industrial companies looking to decarbonise heat up to 1,500 °C, he adds. “Hydrogen can reach slightly higher temperatures, but our battery is suitable for 95% of needs, and we are also exploring the possibility of higher temperature energy storage,” concludes Gordon.

Comments on this publication