In 1884, anyone passing along Whitechapel Road in London’s East End could buy a three-page pamphlet entitled The Autobiography of Joseph Carey Merrick. The supposed author recounted that his pregnant mother has been frightened and almost trampled by an elephant during a carnival parade. Throughout his life, Joseph Merrick (August 5, 1862 – April 11, 1890), known as the Elephant Man, believed that he owed his horrible deformities to that shock suffered by his mother. Today we know that this is not so, but even with the advances of modern science, the medical diagnosis of Merrick’s condition is not yet a closed case.

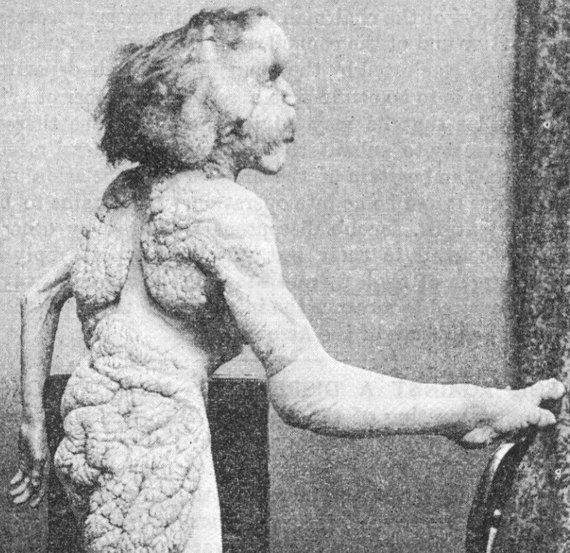

Merrick’s deformities began to appear in his childhood, first with a tumour on his lip that spread across his face, and then with a bony lump on his forehead, as his right arm and his feet grew abnormally and his skin acquired a rough, pitted texture. In contrast, other body parts such as his left arm continued their normal development. Probably it was the appearance of something similar to a trunk —which was later removed— that made his mother relate the anomalies to that episode with the elephant. The first time Merrick was exhibited as a fairground freak, in 1884, it was already under the nickname of the Elephant Man.

Shocking as it may be, it was Merrick himself who chose that degrading way of life. With his mother already deceased and after being rejected by his father and his new stepmother, joining a freak show was his way of escape from the workhouse where he lived, a kind of asylum. After this difficult period touring as a travelling exhibit, in 1886 he was welcomed under the tutelage of surgeon Frederick Treves at the London Hospital, where he would reside until his death.

A long object of study

Those final years were the most pleasing in the life of Merrick. It was also then that the long investigation began to try to identify the evil that afflicted him. The first diagnosis dates back to 1885, when Treves —who had already examined Merrick before welcoming him— presented the case at a meeting of the London Pathological Society. One of the attendees, the prestigious dermatologist Henry Radcliffe Crocker, suggested that Treves’ patient had a combination of cutis laxa and neurofibroma, and that his bone deformities were due to alterations in his nervous system.

That was the only diagnosis made during Merrick’s life, but years after his death his illness continued to receive various and successive names. In 1909 dermatologist Frederick Parkes Weber cited Merrick as a case of Von Recklinghausen disease or neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF-1), a disorder of genetic origin that produces tumours and pigmentation spots; however, the latter were not present in Merrick’s skin. Also during the twentieth century it was proposed that the Elephant Man suffered from Maffucci syndrome and McCune-Albright syndrome, but in both cases without convincing evidence.

The veil over Merrick’s disease began to be drawn back in 1986, six years after the story of the Elephant Man gained popularity thanks to David Lynch’s film. Then Michael Cohen and John Tibbles, from Dalhousie University (Canada), published a study in the British Medical Journal in which they proposed that Merrick suffered from Proteus syndrome, a very rare genetic-based disorder described by Cohen, but whose cause was still unknown.

Two possible diseases

In recent decades, the diagnosis of Proteus syndrome and NF-1 have struggled to coexist: the possibility that Merrick suffered from both diseases was explored by the documentary The Curse of the Elephant Man, produced in 2003 by Natural History New Zealand. The research managed to locate a current relative of Merrick, the granddaughter of a maternal uncle, in order to analyse her genes. At the same time, the producers brought together three teams of geneticists to extract DNA from Merrick’s hair and bones. However, the results were inconclusive. On the other hand, experts in NF-1 have categorically ruled out that the Elephant Man suffered from this disorder.

A decade later, in 2013, new research was undertaken aimed at trying to sequence the Merrick genome. Geneticist Richard Trembath, custodian of the skeleton at the Royal London Hospital and Deputy Director of Health at Queen Mary University in London (today at King’s College London), explained to the BBC that the big obstacle was the preservation of the bones, since they had been bleached several times with substances that degrade the genetic material. The scientists wanted to compare samples of the normal and abnormal parts of the skeleton to test the hypothesis that Merrick suffered from mosaicism, that is, a genetic alteration that arose after conception and that did not affect all his cells.

“This project has and continues to face technical challenges, in particular obtaining sufficient sample material (from both the normal appearance skeleton and the abnormal skeleton) from which to undertake DNA sequencing,” Trembath tells OpenMind. However, the geneticist has a preferred hypothesis: “In the absence of DNA based confirmation, the clinical diagnosis of a severe form of Proteus syndrome remains the most plausible.” If the project is successful, the last chapter of Joseph Merrick’s story could be written, since today there is a known genetic defect related to the disease: “Many but not all cases of Proteus syndrome have been explained by the detection of a change in the DNA sequence of a gene known as AKT1,” adds Trembath.

So far, the penultimate chapter has been written by author Joanne Vigor-Mungovin. Motivated by the research for her recent biography of Merrick, Joseph: The Life, Times and Places of The Elephant Man (Mango Books, 2016), the writer has located in the cemetery of the City of London the place of burial of Merrick’s remains —except for his skeleton— which had been ignored for almost 130 years. The finding will not help clarify the historical mystery about Merrick’s illness, but will help to continue to follow the tracks of an individual who, as Vigor-Mungovin tells OpenMind, “was as unique as was his condition.”

Comments on this publication