Also sometimes known as Viking chess, Tafl (also known as Hnefatafl) is considered the great strategy game of the Celtic and Nordic peoples during the Middle Ages, in addition to being charged with symbolism in the Viking culture. One of the most striking and least known aspects of the game is that its rules are known thanks to botanist and naturalist Carl Linnaeus. It is on this mythical game, about which we have been learning more and more details thanks to recent archaeological research, that we base our challenges for this month.

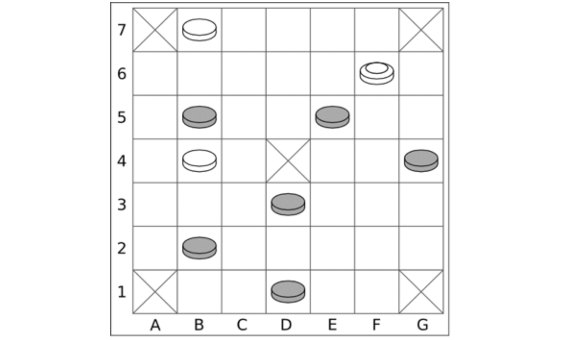

Brainteaser 1: The king escapes in three moves.

Brandubh, the version of the game of the Irish peoples, is one of the simplest and therefore most intuitive versions: on a 7×7 board, two forces, black and white, face off against each other around a king in a central position, which some protect and others attack. All the pieces (including the king, which plays with white) move around the board in straight lines like the rook (or castle) in chess. Any piece can be captured by being surrounded on two opposite sides or caught against an edge; the king is only safe when it is on a cross square and can only escape by reaching the corner squares.

In this game, you start by moving the king. Victory can be guaranteed in just three moves. What must be the first move to achieve this?

——

In one of the best-known Nordic sagas “Hervör and Heidrek“, the god Odin challenges one of the main characters, Gestumblindi, to solve a mysterious enigma: “What women are they who fight together before their defenceless king? Day after day the dark guard him but the fair go forth to attack.” Gestumblindi passes the test by answering that the solution is “the game of hnefatafl: the darker ones protect the king but the white ones attack.”

A symbol of the warriors’ status

It is a response that long challenged and intrigued archaeologists and historians alike, a fascination further encouraged by the many references to the game of tafl in the Nordic sagas. Today we know that hnefatafl is one of the many variants of the so-called tafl games, a family of Germanic and Celtic board games and strategy games that spread throughout central and northern Europe due to Viking influence, and that were very popular between the 5th and 12th centuries, until they were gradually replaced by chess from India.

In the last century and a half, successive excavations and surveys of Viking sites and burials have yielded numerous examples and samples of the game, both game boards and figurines, some more ornate than others. One of the aspects that have most intrigued scholars is the meaning and symbolism attributed to the game, due to its presence in the tombs of many warriors. It seems that the strategic capacity it required, an indispensable virtue for those in charge of leading others in combat, explains this presence, as an element or attribute to define the status of the deceased as an outstanding warrior.

Beyond the archaeological evidence and connotations, there is an even more surprising aspect to this game, one that, in fact, largely opened the door to its discovery and understanding. We actually know the rules that govern it thanks to the invaluable work done by the famous Swedish botanist Carl von Linné (or Charles Linnaeus).

In 1732, the then young Swedish botanist undertook an expedition to Lapland to study the fauna and flora of that remote region. It was a research trip in which Linnaeus would also take advantage of the opportunity to make contact with the Lapp people and learn and document firsthand their lifestyle and customs, among them their fondness for a board game they called tablut. Unfortunately for Linnaeus, he did not speak the Sámi language, so he had to learn the rules of the game by induction by observing numerous games and thereby identify what the objective was, what movements were allowed and how victory was achieved. This information he compiled together with the rest of his observations in his travel book, an English translation of which was published posthumously under the title Lachesis Lapponica: A Tour in Lapland (1811), thereby bequeathing the first recorded instruction manual of the tafl games.

Two forces fighting for a king

In essence, the tafl games involve two players in command of two forces —black and white— positioned around a king in a central position, protected by one and attacked by the other on a chequered square board with one central square. The size of the board can vary (but always with the same odd number of squares per side) and the number of pieces per side (sometimes the same, sometimes twice as many attackers as defenders). The objective of the defending side, which controls the king, is to make the king escape by leaving the board. The objective of the attacking side is to catch the king. All the pieces, including the king, move like the rooks (castles) in chess, vertically and horizontally. Both the king and any of the remaining pieces are removed from the game when they are caught between two opposing pieces in a horizontal or vertical (not diagonal) arrangement, or trapped against one of the edges. And there are squares where the king is safe. These are the basic rules, but there are also more specific details and rules in each version.

However, this information went unnoticed until the end of the 19th century when the English historian H. J. R. Murray made the connection between the description of the Lappish tablut collected by Linnaeus with the tafl game mentioned in the Viking stories and thus opened the door to its study and recognition as an essential element of Viking culture and tradition.

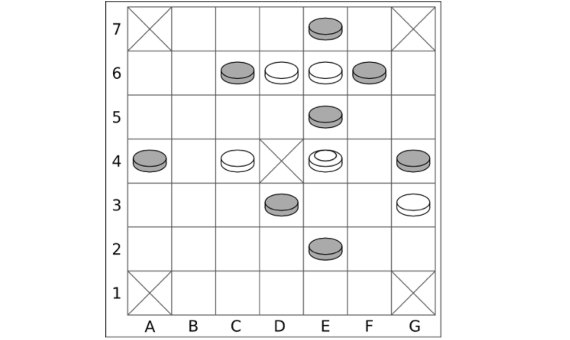

Brainteaser 2: Doomed or not?

In this game the black pieces are in a very advantageous situation to capture the king. It’s white’s turn. Can the king escape this dangerous situation? How?

Comments on this publication