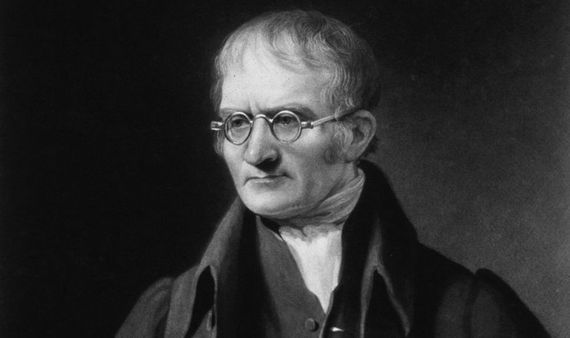

John Dalton could not see the world like most of us: “I have often seriously asked a person whether a flower was blue or pink, but was generally considered to be in jest,” he says in one of the many notes he made on the colour blindness he suffered from, a condition that intrigued him and to which he devoted many hours of study throughout his life. Even so, his vision problems did not prevent him from understanding reality beyond the visible: he found time to become a meticulous meteorologist and a renowned physicist and chemist, and to postulate the first atomic theory in history.

Born into an English family too poor to provide elementary education, John Dalton (6 September 1766 – 27 July 1844) determinedly followed a long and winding path to achieve education and be able to progress in life. Though barred from attending English universities due to his Quaker religion, his extraordinary intelligence and curiosity led him to pursue informal instruction, and at the age of 15 he became a teacher and a prestigious lecturer. After moving to Manchester in search of work, he began to write and publish. Meteorological Observations and Essays (1793), Extraordinary facts related to the vision of colours (1794) and Elements of English Grammar (1801) are just some of his works that illustrate the variety of topics that he studied in depth and his desire to understand the world better.

First theory on matter

Undoubtedly, Dalton’s greatest contribution to science was the first scientific theory in history on the composition of matter. After studying the physical properties of atmospheric air and other gases, he revived and expanded upon the hypothesis enunciated more than 2,000 years earlier by the Greek thinker Democritus, who argued that matter was composed of indivisible particles called atoms.

The publication of Dalton’s postulates in his New System of Chemical Philosophy (1808) had a great impact. In this work he presented his main ideas, such as that matter is made up of atoms, very small and indivisible particles; that atoms of the same element, such as hydrogen, are equal to each other and have the same mass and properties; and that chemical compounds are formed by joining atoms of two or more elements. The writing also included the atomic masses of several known elements, in relation to the mass of hydrogen.

Although it did not achieve absolutely precise measurements, they are the basis of the classification of the periodic table of the elements that we know. The so-called atomic model of Dalton permitted the great advances that chemistry enjoyed throughout the nineteenth century.

Colour Blindness

In his continuous pursuit of new knowledge, Dalton became intrigued with a recurrent theme in his life, his vision problem, which led him to write about himself.

Until then, inability to see colours, which affected some people, had never been described. Dalton’s rigorous and methodical research was so widely recognized that “Daltonism” became a common term for colour blindness. His hypothesis about his own vision problem was that he saw the world through a blue filter, since he believed that the vitreous humour—a gelatinous substance located inside the eyeball—of his own eyes was bluish. Determined that someone would verify his hypothesis, he donated his eyes and gave instructions so that, upon his death, they would be analysed. It turned out that he was mistaken. The vitreous humour in his eyes was as transparent as that of any other person, which led researchers to think that the problem was related to how the brain perceives colours.

What remains of Dalton’s eyeballs is in the basement of the Museum of Science and Industry in Manchester (United Kingdom). In 1995, a group of physiologists from the University of Cambridge collected a small sample of his retina to extract DNA. They discovered that he had a rare type of colour blindness, deuteranopia. In addition to blue and purple, Dalton was only able to recognize one more colour, yellow. From his unique vision of the world, we will always have his atomic model.

Comments on this publication