While the world continues to fret about the spread of a new human virus, a legion of researchers and professionals are constantly engaged in a battle against the spread of countless other pests. If these aren’t making headlines, it’s because they don’t affect us, but rather plants. But if plants are not healthy, we won’t survive. The United Nations has declared 2020 as the International Year of Plant Health “to increase global awareness of the important role of plant health for life on Earth,” Mirko Montuori, a governance specialist with the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), tells OpenMind.

“Plants make up 80% of the food we eat and produce 98% of the oxygen we breathe,” says Montuori. For millions of producers in small rural communities, crops are their only livelihood, and for all of them, pests are enemy number one. “Plants are under constant and increasing threat from pests and diseases.” According to FAO data, 40% of global food crops are lost each year due to these causes, representing losses of more than $220 billion, damage to food security and risk of famine. The outlook for the future is even bleaker, given the FAO’s estimate that by 2050 agricultural production will have to grow by 60% to supply the world’s population.

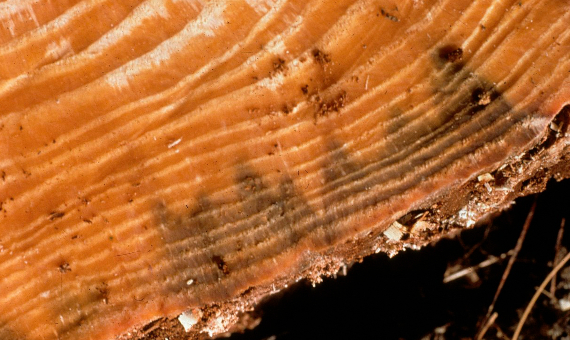

The pine wood nematode worm

As with human viruses, much of this war on pests is focused on containment efforts. One of the cases with a major environmental impact is the pine wood nematode worm (Bursaphelenchus xylophilus), a small tree-killing parasite transmitted by beetles. Originating in North America and then spreading to Asia, it was first discovered in Europe, in Portugal, in 1999. Since then, this country has been struggling to contain the spread of the parasite, while neighbouring Spain is waging a silent war against the penetration of the pest, which has managed to cross the border five times. Three of the outbreaks have been successfully eradicated, with surveillance buffer zones now maintained within a 20 km radius of the border.

The pine nematode serves to illustrate why plant diseases are a growing threat: Montuori stresses that trade and travel are a growing cause of the spread of pests. Although it is likely that the worm’s invasions into Spain are due to beetle migrations, this and many other parasites can spread through such unsuspected sources as wooden pallets. Shipping containers are another common means of spread, and the FAO has a specific initiative to ensure that they are cleaned up to minimize the risk.

Climate change and insects

Of course, climate change is also a major factor involved in harming plant health. Many of these effects have insects as intermediaries; according to the FAO, the abundance of beneficial insects, those that pollinate plants, keep pests at bay and contribute to ecosystem health, has fallen by 80% over the past three decades. Conversely, the risk of harmful insect invasions is increasing.

A clear example of the latter is dramatically taking place in East Africa, which has been suffering from the worst locust infestation in decades since the beginning of 2020. According to experts, this calamity has its origin in the winter of 2018-19, after two cyclones dropped abundant rains in the Arabian Peninsula, between Yemen and Oman. This rarity is attributed to the so-called Indian Ocean dipole, a phenomenon that is intensified by climate change and is also responsible for the recent wave of forest fires in Australia. The rains led to the formation of the core of the plague, which in the summer of 2019 crossed the Red Sea to Somalia and Ethiopia.

Since January, the plague has reached devastating proportions in East Africa, spreading to Kenya and other neighbouring countries and affecting more than 5,000 km² of crops. A 20 km² swarm with one billion insects consumes 2,000 tonnes of vegetation per day, and locust masses have been observed in Kenya covering areas of more than 100 km². The FAO warned that if weather conditions are favourable, the invasion could increase 500-fold by June and spread across the continent, as swarms can move up to 150 km per day.

Prevention tool

As such a disaster is difficult to combat, Montuori insists on the need for prevention. In West Africa, the FAO has already started using a tool developed by Cyril Piou, an ecologist specializing in locust control at the French Agricultural Research Centre for International Development (CIRAD). Piou and his colleagues have developed a remote sensing system that can predict locust infestations earlier than current methods by analysing soil moisture levels from satellite data at a resolution of one kilometre.

“The relationship that we observed is that if in a dry location a signal of increase above 10% of soil moisture lasts for more than 10 days, there is a high chance to observe locusts in this location 70 days later,” Piou explains to OpenMind. “Hence, analysing soil moisture regularly allows to plan the routes of survey teams in the context of preventive management.” The project, called SMELLS (Soil Moisture for Desert Locust Early Survey) and financed by the European Space Agency, is led by the Barcelona-based company IsardSAT.

The SMELLS system facilitates localised treatment with pesticides before locusts start to change from solitary to gregarious behaviour, leading to large swarms. “Localized small size treatments, eventually done with biopesticides, are much less environmentally hazardous than having to deal with huge devastating swarms,” Piou says. The researcher finds it regrettable that a lack of funding has hampered the extension of the system to East Africa and Arabia, which would have prevented the current plague, but hopes that “it will be used in the next few years also in the rest of the desert locust affected countries.”

But of course, when prevention is not available or insufficient, containment and eradication measures continue. In summary, Montuori concludes, the International Year of Plant Health aims to “to make plant health higher on the global agenda, inform the public about the importance to protect plants with their actions and provide policymakers and governments with a solid base to prioritize their decisions.”

Comments on this publication