In Florida there lives a small insect called Dolania americana whose females are the most fleeting of animals: their adult life lasts just five minutes, the time it takes them to fly, mate and lay their eggs. Males don’t live much longer, about half an hour. But another insect, a queen termite, lives 50 years, while the Greenland shark can live up to four centuries, or perhaps even longer. Humans live to be around 80 years old, but France’s Jeanne Louise Calment reached 122, and there are certain families, even certain regions of the world, that are particularly long-lived. Despite scientific progress in understanding the factors of longevity, it is still not known in detail why some species live much longer than others, or why some individuals expire sooner than others. Nor what limit biology imposes on the human lifespan.

Human life expectancy has more than doubled in a few centuries, especially since the Enlightenment; estimates often cite that until 1800 a person lived on average less than 40 years, whereas now this figure is around 80. However, experts warn that statistics can be misleading: these data should not lead to the conclusion that reaching half a century in age was once unheard of, or that the limits of human lifespan have been dramatically extended. Life expectancy is an averaged statistical value, and in former times high infant mortality reduced it substantially, as did the many deaths of young men and women from forced labour, war, disease or miscarriage. Thus, humans in those days could reach ages not much lower than we can reach today, but few did.

Thus, the increase in life expectancy since historical times was initially brought about primarily by a decline in infant mortality. In more recent times, since the mid-20th century, the rise in the survival of older people due to improved living conditions and advances in medicine has become the driving factor. The fact that many more human beings are able to reach advanced ages brings us closer to the parameter we are interested in, maximum longevity, or how long we could live if our bodies continued to function, limited only by the deterioration that comes with age.

On the trail of supercentenarians

One clue might be offered by people who reach extreme ages, the supercentenarians (over 110 years old). But if we look at these long-life record holders, we discover that the records have not been falling as often or as far apart as we might perhaps expect: the first verified supercentenarian was the Dutchman Geert Adriaans Boomgaard, who died in 1899 at the age of 110. The current record is held by Calment, the only verified person to have exceeded 120. But Calment died in 1997; since then no one has surpassed her, and in more than a century the record has only increased by 12 years.

The fact that the number of supercentenarians has grown exponentially since the mid-1970s but that this has not translated into a progressive increase in the longevity record, leads some experts to think that we may already be reaching the maximum of what our biology allows: “I suspect we are quite close to those limits. There has been little increase in maximum lifespan worldwide since around 1990,” geneticist and biogerontologist David Gems, director of research at the Institute of Healthy Ageing at University College London, tells OpenMind. But scientists are not completely in the dark; mathematical models do exist to address such questions.

In 1825, Benjamin Gompertz, a British risk expert with the Alliance Assurance Company, developed the first mathematical approach to the problem of maximum human longevity that has survived to this day. By analysing demographic records, he produced a function according to which, after the age of 30, the chances of dying double every eight to nine years. According to the Gompertz law of mortality, there would come an age at which this increasing risk approaches 100%, and therefore this would be the limit of human life.

But the Gompertz function fails at advanced ages. Although it is still in use today, more complex models try to explain why, for example, there seems to be a plateau in the territory of supercentenarians: some results suggest that at 110 the probability of dying is 50% and remains stable until 115. With the new models, researchers are trying to find out what that biological limit might be. Thanks to Calment, we know that it is possible to live to 122, but what is beyond that? Studies offer tentative figures: 130, or even 150.

The 130-year barrier

According to recent research, it would appear that at a minimum the 130-year barrier is within reach. “Let me use a metaphor,” statistician and mathematician Léo Belzile, from the HEC Montréal business school in Canada, tells OpenMind. “Life is analogous to a road which we travel until death, at which point our journey on Earth ends. A limit to human lifespan would be analogous to an insurmountable obstacle, say a wall, that would be impossible to cross and would force us to stop upon reaching it.”

Belzile and his collaborators have created a model based on demographic data that explores where such a wall, if it exists, might be located. But the model is like a spyglass that reaches only short distances. The results, published in Royal Society Open Science, “make it implausible that there is an upper bound below 130 years,” the researchers write. “We see no wall in sight, but there could be one further down the road beyond what we know already,” Belzile explains.

However, he cautions, this does not mean that reaching 130 will become normal. “Even if there was no limit to human lifespan,” he says, after 110 the possibility of living longer is like flipping a coin every year, “so surviving to 130 would correspond to 20 successive coin tosses landing on heads, an unlikely event.” In short, according to Belzile, we can expect Calment’s record to be broken, but not that blowing out 130 candles will become a frequent event.

But beyond demographic models, and given that it is biology that imposes limits on life, it is in biology that the answers are sought. Ageing and life extension is one of the most active fields of research in biomedicine today, and many are predicting that it will be one of the most lucrative, with a proliferation of biotech start-ups dedicated to the area. In one of the most recent ventures, Altos Labs, investors such as Amazon tycoon Jeff Bezos and Russian-Israeli billionaire Yuri Milner have assembled an impressive line-up of scientists, including Nobel laureates and top researchers.

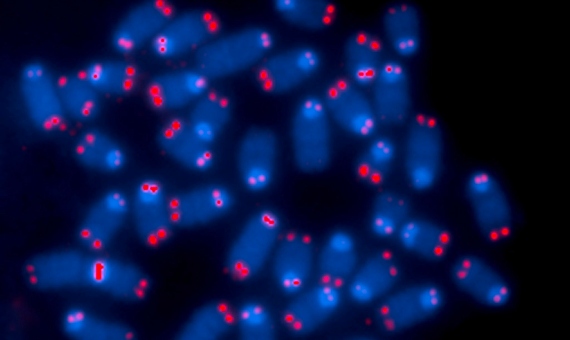

Telomeres and the key to longevity

However, the big questions remain unanswered. Between the late 20th and early 21st centuries, telomeres (those ends of chromosomes that are often compared to the plastic ends of shoelaces) and telomerase (the enzyme that tries to prevent their age-related shortening) were the big stars and were seen as the key to ageing. But since then, researchers have determined that the reality is much more complex. “Many factors affect lifespan,” Janet Thornton, director emeritus of the European Bioinformatics Institute at the European Molecular Biology Laboratory (EMBL) and an expert in the computational biology of ageing proteins, tells OpenMind. “Our analyses suggested that up to about 1/4 of all human proteins are in some way associated with ageing; telomeres is just one of them.”

A 2013 review published in Cell by some of the leading researchers in the field, which has become a landmark study, identified nine hallmarks of ageing; telomere shortening is one of them, along with alterations in: genes, the epigenome (chemical marks on DNA), proteins, mitochondria (the cellular powerhouses), the response to nutrients, and the communication between cells, as well as cellular senescence and stem cell exhaustion.

Although a consensus view has not yet emerged, many experts tend to believe that ageing is a genetic and biochemical program embedded in the evolution of the species. “My own view is that the determinants are largely programmatic (or developmental) in nature,” says Gems. Each species, the biogerontologist adds, has its own program, which determines a give-and-take that is different between short-lived and long-lived species, with the former benefiting sooner but also paying a higher price more quickly.

Within the same species, such as ours, there are also large differences between the longevity of individuals, even between families, which underlines a genetic component that may be of great importance. “There are many genetic differences between individuals, including their susceptibility to different diseases, which can be a major impact on lifespan,” says Thornton. “I suspect (although I do not know) that the expected lifespan of an individual is currently best predicted by considering the lifespan of family members.”

For the time being, and until science comes up with more answers, at least we can be confident that a healthy diet and a healthy lifestyle will help us to keep the years off. “For many individuals there is margin to extend lifespan, particularly those whose lifestyle is currently not so healthy,” says Gems, who is not, however, optimistic: “I suspect that in the coming decades we’ll see decreases in average life expectancy, thanks to increasing levels of obesity, inequality and poor working conditions, all of which shorten lifespan. There have been signs of such changes already in the UK,” he concludes.

Comments on this publication