Sometimes we fall into the void, sometimes we fly like birds. Or not like birds, but like fish, because we are actually swimming through the air. Sometimes we show up for an exam without having studied or even naked. Everything is possible in our dreams, those fragments of film that we experience while we sleep and which range from the comical or the inconsequential to the most terrifying. But do dreams have a common meaning? A simple Google search is all it takes to find an endless number of websites and books that clarify, from A to Z, what each dream storyline actually means. However, many experts caution that dream dictionaries lack any scientific basis. Even researchers cannot agree on whether dreams really have any meaning.

It is not surprising that dreams have fascinated humans since ancient times. The passage from the foundational text of Taoism—the Zhuangzi or Chuang-Tzū—is often cited; in China, in the 3rd century BC, its author Zhuang Zhou asked himself whether when he dreamed he was a butterfly and then woke up, was it he who was really dreaming of being an insect, or was it the butterfly who was dreaming of being Zhuang Zhou? In classical cultures it was common to attribute to dreams a spiritual, religious and even prophetic nature, to such an extent that they could even provoke or prevent wars. And the legacy of this atavism has not disappeared: a 2009 study by psychologists Carey Morewedge and Michael Norton found that dreaming of a plane crash has more influence on cancelling a trip than a conscious thought, a warning by authorities of a terrorist threat, or hearing about an actual plane crash.

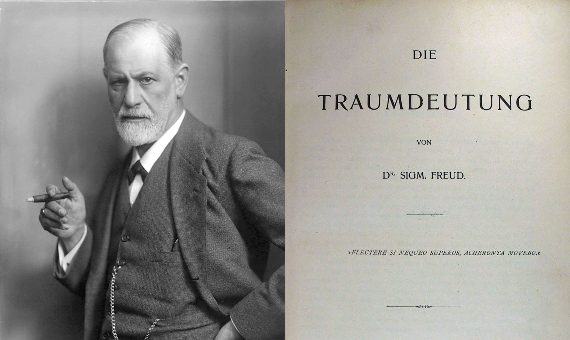

The influence of Sigmund Freud

But as Norton tells OpenMind, that study was about the perception of dreams, not their actual function. And of course, the meaning we ourselves like to attribute to our dreams and their actual interpretation are very different matters. Nevertheless, Morewedge and Norton’s study revealed something whose importance cannot be denied, which is that dreams do have practical meaning in our real lives; they help us make sense of ourselves and the world. Regardless of culture, in both East and West, people surveyed by the psychologists tended to believe that dreams contain “hidden truths,” which is why, according to Norton, for many people they “provide more meaningful information about the world than similar waking thoughts.” But curiously, not all dreams, mainly just those that resonate with us: “Dreams incongruent with existing beliefs and desires are less likely to be endorsed and influence diurnal life.”

As to their actual meaning and function, Sigmund Freud’s pioneering contribution in his 1900 work The Interpretation of Dreams, which initially met with modest success and eventually became a landmark work, is fundamental. However, as is generally the case with the doctrine of the inventor of psychoanalysis, there is an endless debate among experts as to whether his theories meet the rigorous standards of science, something that the philosopher Karl Popper denied. For Freud, dreams were a manifestation of the subconscious inspired by repressed desires, which in his work are often sexual in nature. This repression exerts a self-censorship that masks the latent content of the dream, its real meaning, under a manifest content, the literal content and storyline of the dream that contains a symbology.

Without completely dismissing Freud’s interpretation, Carl Jung argued that there was something else: dreams were a counterpoint, an unconscious compensation of those parts of the psyche that did not manifest themselves consciously. From this sum of light and shadow would come the complete picture of a person’s mind. Jung also proposed the existence of archetypes in the collective unconscious, a symbology common to all human beings, even though dreams had to be interpreted individually.

From the 1950s onwards, researchers such as Calvin Hall investigated the cognitive meaning of dreams, and Ann Faraday and others began publishing books to make it easier for the public to interpret their own dreams, sparking a trend that continues to this day. From studies of thousands of dreams and the psychology of dreamers came the idea that dreams are reflections of waking life, but some experts believe that they have no real purpose and therefore should not be accorded the slightest importance beyond revealing clues about the psychology of the individual dreamer.

A scientific approach to the world of dreams

“From the sleep and dream research that I had been involved in several years ago, I came to the conclusion that dream imagery does not have universal meaning, but is rather conditioned by all those processes that condition our daytime experience, social group identification, culture, personal history, and so on,” Alfred Kaszniak, a neuropsychologist at the University of Arizona, tells OpenMind. Kaszniak’s view, which he developed in collaboration with pioneering researcher Rosalind Cartwright, represents a view shared by many experts today: that dreams are personal, that there are no universal recipes that can give us an automatic translation of their meaning, and that they have only as much significance as we want to give them—which can be none at all if we prefer.

Ultimately, the protracted debate on dream interpretation is explained by the lack of a solid foundation on which to base it, since there is still no definitive explanation as to why we dream. “Unfortunately, there is not present scientific consensus on the function or purpose of dreams,” says Kaszniak. “Some investigators think that dreams, or their brain physiological correlates, play a functional role in the consolidation in memory of daytime experience, while others think that dream imagery is epiphenomenal of the brain physiological processes.”

According to the latter hypothesis, dreams would be nothing more than a translation that our mind produces from simple bursts of activity that are part of the nocturnal maintenance of our brain. In that case, attempting to confer meaning on them would amount to little more than looking for shapes in the clouds. However, this purely mechanistic perspective is not favoured by much of the scientific community, which continues to assign dreams a meaning that is relevant in the psychological context of one’s emotions and motivations.

Nor has the world of dreams remained unaffected by the COVID-19 pandemic. From the experiences posted by numerous people on social media, some researchers have noted that there seems to have been an increase in reports of particularly intense dreams. But while we can understand that stressful and anxious situations such as a pandemic can lead to these disturbances, and that good mental health can help alleviate them, there is still much we do not understand. Why we keep returning to recurring dreams. Or why we have lucid dreams, those in which we know we are dreaming; why certain people are more prone to them, and how it is possible to stimulate them. Today researchers are even learning how to manipulate dreams, which may open new avenues towards understanding a nocturnal life that is not usually as surreal as we sometimes think, but which never ceases to surprise us.

Javier Yanes

Comments on this publication