The slogan of the Spanish foundation for orphan drugs and rare diseases (Mehuer Foundation) says it all: “We can’t always choose the way we wish to be different”, a sentiment echoed by researchers and associations of patients with rare diseases in all corners of the planet.

A rare disease is considered one that affects a very limited proportion of the population. Although each legislation establishes different criteria -in Europe a disease is considered rare when it affects one out of every 2,000 people, whereas in the United States it is defined as being a disease affecting fewer than 200,000 individuals- in global terms it can be stated that 7% of the world population currently suffers from a pathology classified as a rare disease, according to the World Health Organization (WHO). In other words, over 250 million people.

Underlying this term of “rare disease”, or “orphan disease” as it is also known, are around 7,000 classified diseases affecting the physical capacities, mental abilities and the sensorial and behavioral capacities of the patients who suffer from them.

Unfortunately today we know the biological cause of only around 300 of these diseases, and there is treatment -sometimes not very effective- for fewer than half. The average time taken to reach a diagnosis for one of these patients is around five years.

Amid this avalanche of disheartening figures, there is fortunately a glimmer of hope. In recent years, international policies and a growing awareness in the population and the media point to a sea change in this social drama.

The milestone marking the before and after in the study of rare diseases came in 1983, when the government of Ronald Reagan passed the Orphan Drug Act, at the urging of a powerful lobby of family associations in the United States.

Until that time, this type of diseases had failed to capture the interest of the pharmaceutical industry for obvious financial reasons. The small group of patients who are the target for this type of drugs and the high cost of investing in R+D made it difficult to find any research in the industry that would respond more to a moral than to a business imperative.

The new set of laws proposed at that time by the American government speeded up the times and reduced the costs of researching and developing drugs against these pathologies. What’s more, they laid the groundwork which made it attractive for small innovative companies to invest in this type of R+D thanks to the creation of the notion of the Orphan Drug. This series of measures was rapidly copied and adapted in numerous countries. The European Union launched a common policy in this area in 1999.

Since then, the term orphan drug has been understood as meaning drugs that while targeting only a small group of patients respond to the needs of public health. The incentive for these drugs that are not a priori of interest to the pharmaceutical industry from the point of view of market figures lies in the subsidies for their development and approval.

Measures such as the market exclusivity of the drug so that no other medication -unless it is demonstrated to be more effective- can be prescribed for this pathology for a specified time, or the permission to charge a high price for these drugs, have helped to guarantee that the pharmaceutical companies can recover a large part of their investment in these developments.

In 2003, the North American agencies assessed the progress and summarized their findings as follows:

- Private R+D in rare diseases had increased by 5,000%

- The cost of clinical trials (essential before any drug can be administered) was between $10 and $15 million, whereas in diseases such as cancer it could easily exceed $500 million.

- The average duration of clinical trials was three years compared to six for diseases like cancer.

- The time between the discovery of a promising molecule and the administration of the finished drug has fallen to an average of six years compared to the 12-14 years commonly seen for other diseases.

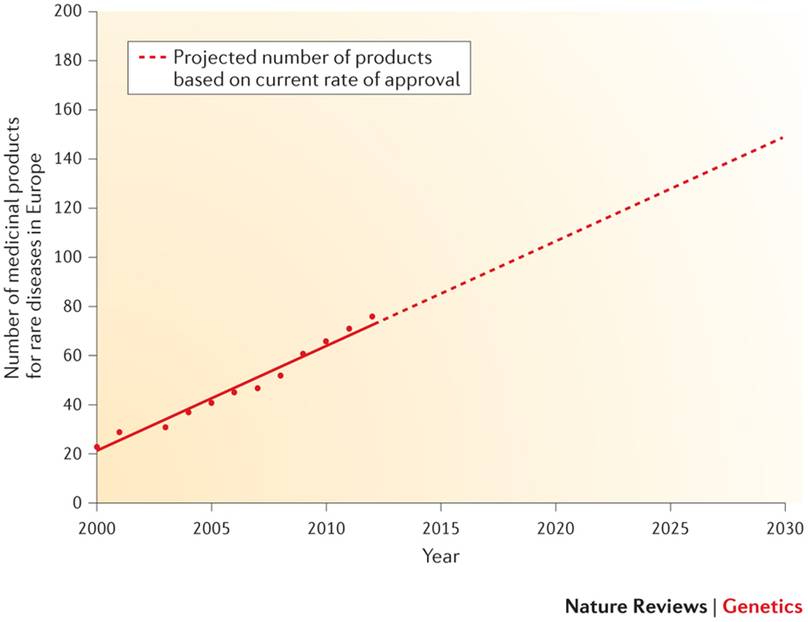

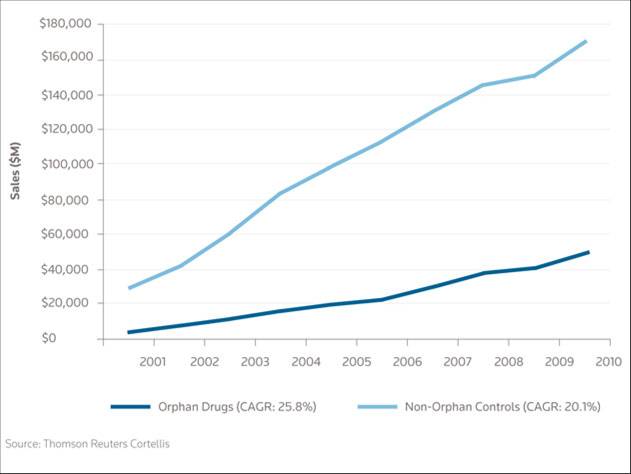

Looking backwards and also looking to the future, we can say that these policies to simplify clinical trials and incentives for R+D by biotechnological SMEs have led to a dramatic increase in the number of orphan drugs available:

At the present time, and knowing that the growth rate of profits from investigating new drugs for these pathologies is already greater than in non-rare diseases, we can predict that towards 2020 there will be over 100 new drugs against rare diseases available to patients in Europe.

What’s more, an in-depth study of the socio-economic impact of rare diseases has shown that for many of them the cost of assistance and palliative care is between approximately $150,000 and $1 million a year per patient, compared to the usual maximum of $10,000 it costs to treat a common disease. In short, in terms of costs, the discovery of this type of drugs represents considerable savings for healthcare systems.

The fact of the matter is that there are still thousands of rare diseases on which to begin work, and the current rate of development is far from satisfactory for the patients themselves. Therefore international agencies, and particularly the European Medicines Agency (EMA, with headquarters in London) and the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA, headquarters in Washington DC) continue to come up with programs to incentivize R+D, or offer soft credits that cover up to 50% of the costs of the clinical phases, in order to speed up these developments.

As a final thought and over and above all the good reasons that might encourage a large or small bio-pharmaceutical company to take part in designing new orphan drugs, the primary reason that should motivate us is that as a society we have the moral duty to take care of those who -for whatever reason- need our help. Just as we cannot discriminate against patients for reason of gender, economic resources or place of birth, nor can we do so because of the statistical incidence of their pathology.

Sources

Spanish Federation of Rare Diseases (http://www.enfermedades-raras.org/)

Orphanet (http://www.orpha.net/consor/cgi-bin/index.php)

European Medicines Agency (http://www.ema.europa.eu/ema/)

Food and Drug Administration (http://www.fda.gov/)

Boletín de la Organización Mundial de la Salud (http://www.who.int/bulletin/volumes/90/6/12-020612/es/)

Antonio Molina

Beacon Biomedicine Founder, company associated with Parque Científico de Madrid

Comments on this publication