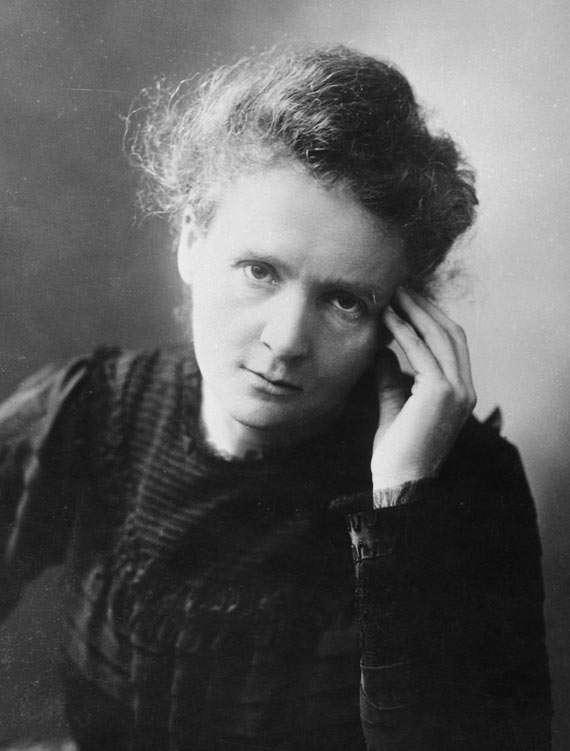

The nineteenth century had one final surprise left for science. Physicists and chemists were finally comfortable with their basic laws, which were able to explain anything, until march, 1, 1896 the French physicist Becquerel (15 December 1852 – 25 August 1908) accidentally discovered an entirely new phenomenon. He left a package of uranium salts on top of a roll of photographic plate in a drawer, and days later found that the plate had darkened as if it had been exposed to light; he thought that these salts had emitted penetrating rays that were able to pass through metal. However, Becquerel lost interest in the topic and passed it on to a Polish student who hadn’t yet chosen her doctoral thesis topic. She, Marie Curie (7 November 1867 – 4 July 1934), investigated more thoroughly these stones that constantly emitted so much energy and didn’t seem to be consumed, and she baptized this phenomenon as radioactivity.

At the age of 24, Marie Curie (then Marie Skłodowska) had emigrated from Poland, where women could not undertake university studies. She then enrolled in the Sorbonne, the most famous university in France. She devoured one subject after another, hardly eating and living in an unheated attic. She was first in her class and at the end of her studies she met her husband, physicist Pierre Curie (15 May 1859 – 19 April 1906), who also became her scientific partner. Marie discovered that Becquerel rays came from the interior of uranium atoms and that only one other element, thorium, emitted similar rays. She then studied the uranium minerals and was astonished that one of them, pitchblende (or uraninite), was more radioactive than pure uranium; her hypothesis was that the rock contained a small amount of something unknown and very, very radioactive.

Pierre saw it so clearly that he abandoned his own research to focus on helping Marie and, together, they soon discovered in pitchblende two new elements: polonium and radium, each one more radioactive than the other. To obtain them in quantity and to be able to study them, they invested their savings in tons of pitchblende and stored it in a leaky borrowed shed. There, the couple would be found at the end of their workday as teachers, crushing and dissolving the ore with acids. It was hard work, amid toxic gases and increasingly pure radioactive products. Five years later, the tons of ore had been reduced to 0.1 grams of radium salt, so radioactive that it glowed in the dark and produced burns on their skin. Marie Curie was then able to present her thesis, which was the most productive one in history since it gave her the title of doctor and also two Nobel prizes: the first one that same year (1903), shared with Becquerel and her husband; the second one was awarded to her alone (1911) as Pierre had died five years earlier, struck by a horse drawn vehicle.

The Curies’ history had everything: romance, idealism, sacrifice, tragedy and a new source of heat —radium, which seemed inexhaustible. Science jumped from specialized journals to the newspapers’ headlines. Meanwhile, Rutherford had discovered that radioactive materials did waste away but disintegrated, transforming themselves into other elements: it was the alchemists’ dream come true. For Vassily Kandinsky, who in those years created the first works of abstract painting, “that radioactivity thing” was the symbol of the disintegration of the entire world.

It wasn’t so bad; all that had to be done was to create a new physics to explain this and other phenomena. Marie Curie lived to see it and died at age 67 of leukemia, an illness probably caused by all the radiation she received. In fact, her laboratory notebooks remain highly radioactive: 1,600 years will have to pass before half the radium that fell on them is consumed.

Comments on this publication