When British archaeologist Leonard Woolley found the tomb of Queen Puabi in the ancient Sumerian city of Ur in present day Iraq in 1928, he unearthed an incredible treasure trove for the world. But amongst so much wealth there was also a more humble discovery: the first historical representation of the use of drinking straws. According to archaeologists, Sumerians and Babylonians used straws not for fashion or whimsy, but to drink their dense beer without swallowing the dregs or chunks from the fermentation process. We review the technological evolution of this invention whose origin is lost in history and that began to be mass-produced 130 years ago.

Although the basic version was a simple hollow reed, notable characters like Queen Puabi had luxurious little straws made of precious metals that were part of their funerary offerings. But narrowing the history of the drinking straw to the Sumerians or Babylonians would be too narrow; some biologists suggest that the proboscis of certain insects, like butterflies, function in part like a straw, so nature actually invented it before us.

The usual account attributes the invention of the drinking straw to the American Marvin Chester Stone in 1888, but this is inaccurate. In addition to the historical precedents, before Stone’s invention there were previous examples. In 1870, Eugene Chapin patented a flexible “drinking tube for invalids” that was attached to the cup by means of a clamp. Nine years later, William Henry Brown invented a “utensil to mix and drink liquids,” a straw with a strainer perforated at the base, an addition that had already been in use for centuries in South America for the consumption of mate.

The first disposable artificial straw

To be precise, Stone’s contribution was the first disposable artificial straw. According to the Lemelson Center for Studying Invention and Innovation at the Smithsonian Institution, Stone was in Washington for a day, savouring a mint julep with friends after work. As was customary at the time, Stone was sipping his cocktail with a stalk of rye grass, but he was disturbed by the residue and the grassy taste that remained when this natural straw turned to mush in the drink. It occurred to him then to roll a strip of paper around a pencil, then remove it and fix the structure of the paper with glue.

-

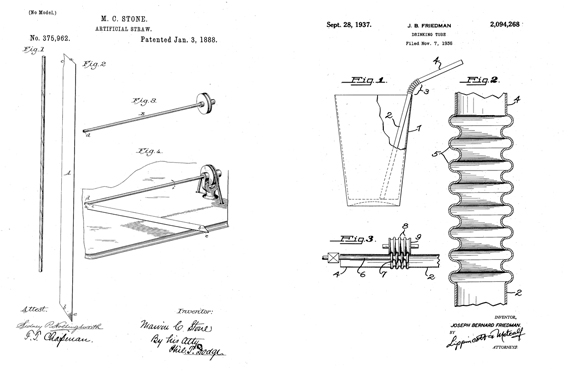

- Patents from Marvin Stone (left, 1888) and Joseph Friedman (right, 1937). Credit:

US Patent and Trademark Office

Stone, an inventor like his father, was at that time dedicated to making paper cigarette holders, so he had the resources to do something with his idea. After patenting it in England in 1887, on January 3, 1888 he obtained patent number 375,962 in the USA for his “artificial straw” with which he intended to “provide a cheap, durable, and unobjectionable substitute for the natural straws commonly used for the administration of medicines, beverages, etc.” The straw would be made with Manila paper and covered with paraffin to waterproof it. In addition, Stone ordered that the tube be “preferably colored in imitation of the natural straw,” so that it would not be strange to the consumer.

Stone’s invention was immediately successful: by 1890, his factory was already producing more straws than cigarette holders. According to the company that today bears the name of the inventor, Stone Straw Limited, in 1906 the process was mechanized with the first machine that rolled the paper. The same system would then be applied to materials other than paper for the manufacture of radios, electrical devices and miscellaneous products.

Others would try to emulate Stone’s success by proposing improvements, such as a straw with one flattened end so that the liquid does not slide back into the vessel when suction ceases, or straws with a retractable mechanism to pop out of the bottle when opened, or even a flexible and edible straw made with chewing gum, flour, sugar and starch. Stone himself patented other models, such as a double straw that was achieved by rolling the paper longitudinally from both edges to give it a letter “B” shaped section or a similar one made by compressing the tube along its center line.

The flexible bendy straw

However, none of these ideas would triumph, and Stone’s basic design would prevail for four decades. Then one day Joseph Bernard Friedman, seeing how his daughter Judith was struggling to get a straw from her milkshake cup on the cafeteria counter into her mouth, inserted a screw into the paper tube, marked the grooves with dental floss and then pulled out the screw again. The flexible bendy straw was born, which Friedman patented in 1937.

Curiously, none of the straw makers of the time showed an interest in buying the Friedman patent, so in 1939 the inventor eventually founded his own company, the Flexible Straw Corporation. The Second World War paralyzed the development of his business, but in 1947, once the conflict had ended, he began selling his flexible straws, initially to hospitals. In the 1960s they replaced paper with plastic, and since then the straw has not ceased to be the subject of innovations with greater or lesser success: telescopic, extravagant shapes, changing colors, with flavours…

Today the successor straws of the ideas of Stone and Friedman are used by millions around the world every day and, of course, are also discarded by the millions. The problem of plastic waste has led to the introduction of biodegradable materials, but has also inspired a return to paper with 21st-century materials and technologies —following the original design of Stone. This is a historical vindication of a person little known today, a true inventor who was also appreciated for his philanthropic work. But who, above all, helped to better connect the human being to his drink.

Comments on this publication