What do Francis Crick, co-discoverer of the structure of DNA and 1962 Nobel Prize winner, and former singer and journalist Raël, leader of a UFO cult that advocates free love among its members, have in common? The link seems unlikely, but it exists, and is called directed panspermia: the hypothesis that life on Earth is the product of the designs of an advanced alien civilization.

Of course, that’s where the similarities end. The leader of the Raelians bases his beliefs on his alleged personal encounter with beings from another world. Crick, meanwhile, asked himself how it was possible that nature had simultaneously invented two mutually interdependent elements of life: the genetic material –nucleic acids, such as DNA or RNA– and the mechanism necessary to perpetuate it –the proteins called enzymes–. The synthesis of the nucleic acids depends on the proteins, but the synthesis of the proteins depends on the nucleic acids. Faced with this chicken-and-egg problem, Crick and his colleague Leslie Orgel reasoned that life should have arisen in a place where there exists a “mineral or compound” capable of replacing the function of the enzymes, and from there it would have been disseminated to other planets like Earth by “the deliberate activity of an extraterrestrial society.”

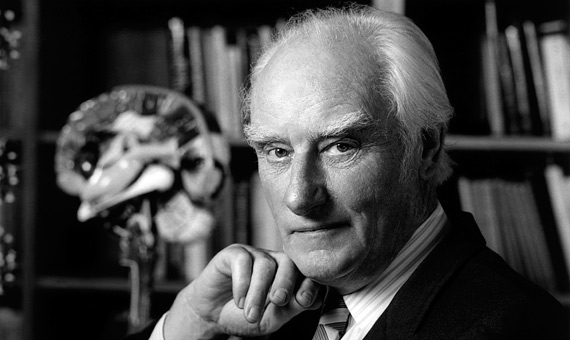

The truth is that directed panspermia does not detract from Crick’s thinking at all. Quite the contrary, it reveals the powerful workings of a theoretical, incisive and restless mind, eager for rational answers, even unconventional ones. To understand how Crick came to the idea of panspermia, we must go back a few years. The son of shoemaker Weston Favell (Northampton, UK), Francis Harry Compton Crick (June 8, 1916 – July 28, 2004) reached the end of his childhood with the main aspects of his identity already defined: his penchant for science and his atheist convictions. As for the first, he chose physics.

Interestingly, molecular biology might have lost one of its founding fathers had it not been for the war. Crick began his research at University College, London working on what he described as “the dullest problem imaginable” – measuring the viscosity of water at high pressure and temperature. With the outbreak of World War II, he was drafted into the army to work on the design of mines. After the end of the conflict, he discovered that his equipment had been destroyed by a bomb (in his autobiography he spoke of a “land mine”), which allowed him to leave this tedious research.

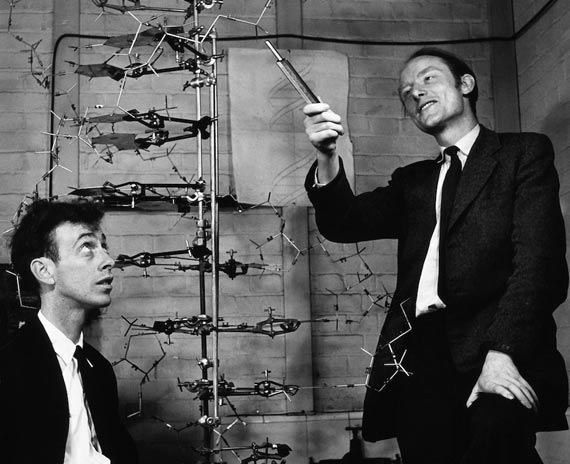

Crick then had to choose a new field of research, and that was when he discovered what he called the gossip test: “what you are really interested in is what you gossip about.” In his case it was “the borderline between the living and the nonliving, and the workings of the brain,” in a nutshell – biology, or, as a physicist – biophysics. He began working on the structure of proteins in the Cavendish Laboratory of Cambridge, until he met an American named James Watson, twelve years younger than him but already with a PhD that Crick had not yet obtained for himself.

The two researchers discovered that they shared a hypothesis. At that time it was believed that the seat of inheritance lay in proteins. Crick and Watson thought that genes resided in that unknown substance of the chromosomes, deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA). And that conviction, along with the participation of Maurice Wilkins and Rosalind Franklin, would give birth on February 28, 1953 to one of the greatest discoveries of twentieth century science, the double helix of DNA. The work was published in Nature on April 25 of that year. Crick would not obtain his PhD until the following year.

But although Crick is known primarily for being one of the founders of this milestone of molecular biology, the truth is that he himself laid the first rails of this new science. It was he who proposed that DNA was transcribed to RNA and that this was translated by means of adapter molecules in charge of converting the genetic code for proteins, the building blocks of life. And it was this “central dogma” of biology, as he himself baptized it, which led him to publish in 1973 his hypothesis of panspermia, by then such an elegant idea that it even counted astrophysicist Carl Sagan among its proponents.

Only years later would it be discovered that RNA can act by itself as an enzyme without the intervention of proteins, thus solving the problem that inspired panspermia. In 1993, Crick and Orgel published an article that no longer made any mention of an “extraterrestrial society”. The chicken-and-egg problem “could be resolved if, early in the evolution of life, nucleic acids acted as catalysts,” they wrote.

By this time Crick had changed continents and fields of study; in 1976 he moved to the Salk Institute in La Jolla (California, USA) for a one year sabbatical that would end up lasting for almost three decades. It was there that he settled his unfinished business with the second of his gossips: the brain. For the rest of his career, and in collaboration with neuroscientist Christof Koch, at the California Institute of Technology (Caltech), he devoted himself to trying to locate consciousness in the brain matter. “You, your joys and your sorrows, your memories and your ambition, your sense of personal identity and free will, are in fact no more than the behavior of a vast assembly of nerve cells and their associated molecules,” he wrote in 1994.

He never managed to unravel the problem of consciousness, although he made significant advances in the knowledge of visual perception. In 2004, he lost his battle against colon cancer, but never lost the courage or the passion for the study of life. According to Christof Koch, “he was editing a manuscript on his death bed, a scientist until the bitter end.”

Javier Yanes for Ventana al Conocimiento

@yanes68

Comments on this publication