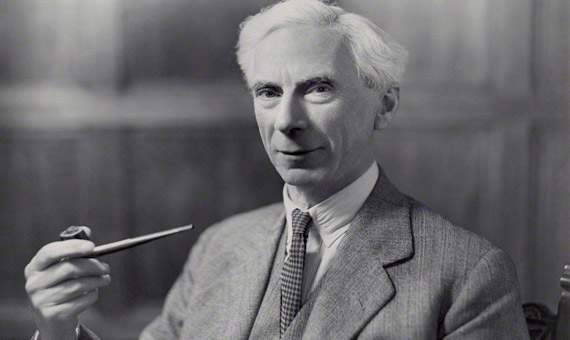

Bertrand Russell (18 May 1872 – 2 February 1970) could be just a brilliant mathematician who won a Nobel Prize. But he is also a philosopher who, by his writings, won the award in the category of Literature. He is the social critic who defended the rights of women and who lost work to support sexual freedom in the early twentieth century. He is the pacifist whose rejection of the First World War took him to jail. He is the activist who opposed Hitler, Stalinism, the US invasion of Vietnam, nuclear bombs and racial segregation. He is the one who made peace his struggle. It is he who —three months before his death, at the age of 97— appealed to the Secretary General of United Nations to support a commission against the war crimes committed by the Americans in Southeast Asia. For all his contributions, Russell is defined as one of the most important philosophers of the twentieth century. But it was mathematics, according to Russell himself, that was his chief interest and source of happiness.

To understand Russell’s prolific career, one has to travel to his past. Belonging to one of Britain’s most prominent aristocratic families —his grandfather was Prime Minister twice under Queen Victoria— he was orphaned at age three. The secular education to which his parents, radical freethinkers, would have directed him, had nothing to do with the one he actually received from his grandmother. The strict and repressive moral control led to his becoming a shy, withdrawn and solitary boy, whose rescue came from geometry. According to his own autobiography, it was his desire to know more about mathematics that kept him away from suicide. “At the age of 11 I began Euclid, with my brother [seven years his senior] as my tutor,” he wrote. “This was one of the great events of my life, as dazzling as first love. I had not imagined there was anything so delicious in the world.”

As a teenager, readings in advanced mathematics led him to rethink some of the dogmas of the Christian religion. At 18, he rejected life after death and the existence of God, becoming an agnostic, one of the traits that would define him until the end of his life. At that age, Russell entered Trinity College of Cambridge to begin his studies in mathematics, which he supplemented, years later, with those of philosophy. Although he graduated with honours in both subjects, he later recognized that he had learned little from his university professors; not so from his companions, who helped him to be less solemn and to acquire a sense of humour.

The discovery of mathematical logic

With the start of the new century, a key event took place in Russell’s story. He went to Paris to the second International Congress of Mathematicians, where he met Giuseppe Peano, an icon in symbolic logic. Fascinated by his speech, Russell devoured all the Italian’s publications. “For years I had been endeavouring to analyse the fundamental notions of mathematics, such as order and cardinal numbers. Suddenly, in the space of a few weeks, I discovered what appeared to be definite answers to the problems that had baffled me for years. And in the course of discovering these answers, I was introducing a new mathematical technique, by which regions formerly abandoned to vagueness of philosophers were conquered by the precision of exact formulae,” he wrote.

That same year, Russell began to write The principles of mathematics, managing to write 200,000 words in only three months. Its publication in 1903 was the prelude to the pinnacle work that the Briton would write together with Alfred North Whitehead: Principia Mathematica. These three volumes (published between 1910 and 1913) form an axiomatic system onto which all mathematics can be based and with which the authors tried to explain how all mathematical truths are, in an important sense, reducible to logic, in this way eliminating any connection that could be believed to exist between numbers and mysticism.

Creating a happier world

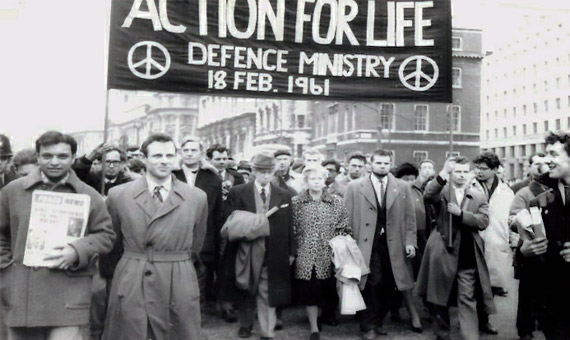

For the rest of his life, Russell continued to write numerous philosophical and social treatises that even led him to spend six months in jail in 1918 for his anti-war campaign, where he wrote his Introduction to Mathematical Philosophy. This broad viewpoint was one of the reasons why the Swedish Academy decided to reward Russell in 1950 with the Nobel Prize for Literature: “In recognition of his varied and significant writings in which he champions humanitarian ideals and freedom of thought.”

At the end of his autobiography, Russell reflects on his life and concludes that since his youth, his whole “serious” life has been due to two factors: “I wanted, on the one hand, to find out whether anything could be known; and, on the other hand, to do whatever might be possible toward creating a happier world.” The events of the twentieth century put a dent in his optimism, but did not defeat it: “I may have thought the road to a world of free and happy human beings shorter than it is proving to be, but I was not wrong in thinking that such a world is possible.”

Comments on this publication