The American media system has undergone significant transformations since the advent of new media in the late 1980s. During the past decade, social media have become powerful political tools in campaigns and governing. This article explores three major trends related to the rise of social media that are relevant for democratic politics in the United States. First, there is a major shift in how and where people get political information, as more people turn to digital sources and abandon television news. Next, the emergence of the political “Twitterverse,” which has become a locus of communication between politicians, citizens, and the press, has coarsened political discourse, fostered “rule by tweet,” and advanced the spread of misinformation. Finally, the disappearance of local news outlets and the resulting increase in “news deserts” has allowed social-media messages to become a primary source of information in places where Donald Trump’s support is most robust.

The political media system in the United States has undergone massive transformations over the past three decades. The scope of these new media developments is vast, encompassing both legacy sources as well as entirely novel communication platforms made possible by emerging technologies. The new media era began with the infotainment trend in the 1980s when television talk shows, talk radio, and tabloid papers took on enhanced political roles. Changes became more radical when the Internet emerged as a delivery system for political content in the 1990s. Digital technology first supported platforms where users could access static documents and brochures, but soon hosted sites with interactive features. The public gained greater political agency through technological affordances that allowed them to react to political events and issues, communicate directly to candidates and political leaders, contribute original news, images, videos, and political content, and engage in political activities, such as working on behalf of candidates, raising funds, and organizing protests. At the same time, journalists acquired pioneering mechanisms for reporting stories and reaching audiences. Politicians amassed news ways of conveying messages to the public, other elites, and the press, influencing constituents’ opinions, recruiting volunteers and donors, and mobilizing voters (Davis and Owen, 1998; Owen, 2017a).

The evolution of social media, like Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube, from platforms facilitating networks among friends to powerful political tools has been an especially momentous development. The political role of social media in American politics was established during the 2008 presidential election. Democratic presidential candidate Barack Obama’s social-media strategy revolutionized campaigning by altering the structure of political organizing. Obama’s campaign took on the characteristics of a social movement with strong digital grassroots mobilization (Bimber, 2014). The campaign exploited the networking, collaborating, and community-building potential of social media. It used social media to make personalized appeals to voters aided by data analytics that guided targeted messaging. Voters created and amplified messages about the candidates without going through formal campaign organizations or political parties (Stromer-Galley, 2016). The most popular viral videos in the 2008 campaign, BarelyPolitical.com’s “Obama Girl” and will.i.am’s “Yes, We Can,” were produced independently and attracted millions of viewers (Wallsten, 2010). In this unique election, the calculated strategies of Obama’s official campaign organization were aided by the spontaneous innovation of voters themselves. Going forward, campaigns—including Obama’s 2012 committee—would work hard to curtail outside efforts and exert more control over the campaign-media process (Stromer-Galley, 2016).

The new media era began with the infotainment trend in the 1980s when television talk shows, talk radio, and tabloid papers took on enhanced political roles

Since then, social media’s political function in campaigns, government, and political movements, as well as their role in the news media ecosystem, has rapidly broadened in reach, consequence, and complexity. As political scientist Bruce Bimber points out: “The exercise of power and the configuration of advantage and dominance in democracy are linked to technological change” (2014: 130). Who controls, consumes, and distributes information is largely determined by who is best able to navigate digital technology. Social media have emerged as essential intermediaries that political and media actors use to assert influence. Political leaders have appropriated social media effectively to achieve political ends, ever-more frequently pushing the boundaries of discursive action to extremes. Donald Trump’s brash, often reckless, use of Twitter has enabled him to communicate directly to the public, stage-manage his political allies and detractors, and control the news agenda. Aided by social media, he has exceeded the ability of his modern-day presidential predecessors to achieve these ends. Social-media platforms facilitate the creation and sustenance of ad hoc groups, including those on the alt-right and far left of the political spectrum. These factors have encouraged the ubiquitous spread of false information that threatens to undermine democratic governance that relies on citizens’ access to quality information for decision-making.

Social media have low barriers to entry and offer expanded opportunities for mass political engagement. They have centralized access to information and have made it easier for the online population to monitor politics. Growing numbers of people are using social media to engage in discussions and share messages within their social networks (Owen, 2017b). Effective use of social media has contributed to the success of social movements and political protests by promoting unifying messages and facilitating logistics (Jost et al., 2018). The #MeToo movement became a global phenomenon as a result of social media spreading the word. Actress Alyssa Milano sent out a tweet encouraging women who had been sexually harassed or assaulted to use the #MeToo hashtag in their social-media feed. Within twenty-four hours, 4.7 million people on Facebook and nearly one million on Twitter had used the hashtag. The number grew to over eighty-five million users in eighty-five countries on Facebook in forty-five days (Sayej, 2017).

Still, there are indications that elite political actors have increasingly attempted to shape, even restrict, the public’s digital influence in the political sphere. Since 2008, parties and campaign organizations have sought to hyper-manage voters’ digital engagement in elections by channeling their involvement through official Web sites and social-media platforms. They have controlled voters’ access to information by microtargeting messages based on users’ personal data, political proclivities, and consumer preferences derived from their social- media accounts. Further, a small number of companies, notably Google and Facebook, have inordinate power over the way that people spend their time and money online. Their ability to attract and maintain audiences undercuts the ability of small firms, local news outlets, and individuals to stake out their place in the digital market (Hindman, 2018).

The political role of social media in American politics was established during the 2008 presidential election. Democratic presidential candidate Barack Obama’s social-media strategy revolutionized campaigning by taking on the characteristics of a social movement with strong digital grass-roots mobilization

This article will focus on three major trends related to the rise of social media over the past decade that have particular significance for democratic politics and governance in the United States. First, the shift in audience preferences away from traditional mass media to digital sources has changed how people follow politics and the type of information they access. Many people are now getting news from their social-media feeds which contributes to rampant political insularity, polarization, and incivility. Next, the emergence of the political “Twitterverse” has fundamentally altered the way that politicians, citizens, and the press convey information, including messages of significant import to the nation. The “Twitterverse” is comprised of the users of the microblogging platform as well as those exposed to its content when it is disseminated through other media, such as twenty-four-hour news channels. Twitter and other social media in the age of Trump have advanced the proliferation of disinformation, misinformation, “alternative facts,” and “fake news.” Importantly, Donald Trump’s presidency has ushered in an era of “rule by tweet,” as politicians make key pronouncements and conduct government business through Twitter. Finally, the spread of “news deserts”—places where local news outlets have disappeared—has compromised the institutional media’s ability to check false facts disseminated by social media, hyper-partisan sources, and bots propagating computational propaganda.

Shifting Audience Media Preferences

The number of options available to news consumers has grown dramatically as content from ever-increasing sources is distributed via print, television, radio, computers, tablets, and mobile devices. More Americans are seeking news and political information since the 2016 presidential election and the turbulent times that have followed than at other periods in the past decade. At the same time, seven in ten people have experienced news fatigue and feel worn out from the constant barrage of contentious stories that are reported daily (Gottfried and Barthel, 2018). This is not surprising when the breaking news within a single day in September 2018 featured Dr. Christine Blasey Ford’s testimony that she had been sexually assaulted by Judge Brett Kavanaugh, a nominee for the US Supreme Court; the possibility that Deputy Attorney General Rod Rosenstein, head of the investigation into Russian intervention in the 2016 presidential election, could be fired by President Donald Trump for suggesting in a private meeting that steps be taken to remove Trump from office; and comedian Bill Cosby being sentenced to prison for sexual misconduct and led away in handcuffs.

Where Americans Get Their News

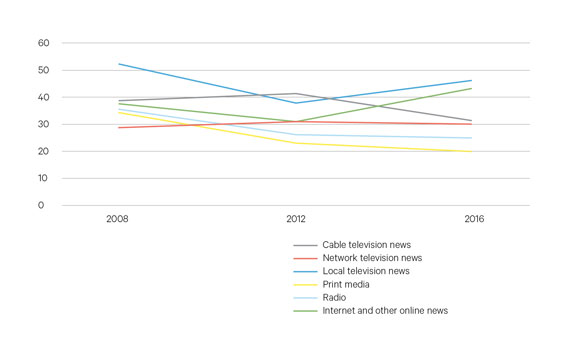

One of the most notable developments in the past decade has been the shift in where and how Americans get their news and information about politics. There has been a marked transition in audience preferences away from traditional media, especially television and print newspapers, to online news sources and, more recently, news apps for smartphones. Social media have become major sources of news for millions of Americans, who either get political information deliberately through subscriptions or accidentally come upon it in their newsfeed. Trends in the public’s media use become most apparent during periods of heightened political awareness, such as during political campaigns. Thus, Table 1 presents the percentage of adults who frequently used specific types of media to get information about the 2008, 2012, and 2016 presidential elections.

Table 1. Percentage of American adults using media often in the 2008, 2012, and 2016 presidential elections. (Source: Pew Research Center, data compiled by the author.)

The excitement surrounding the 2008 election, largely attributed to the landmark candidacy of Barack Obama, coupled with digital breakthroughs in campaigning, caused regular online news use to escalate to 37% of the public from 9% in 2006. Attention to news online dwindled somewhat in 2012 to 31%, as voters were less interested in the 2012 presidential campaign where President Obama sought reelection against Republican challenger Mitt Romney. However, the public’s use of news delivered online and through apps surged to 43% during the 2016 election that pitted Democrat Hillary Clinton against Republican Donald Trump.

When cable, network, and local channels are considered together, television was the main source of campaign information throughout this period for a majority of the public. Network TV news had seen a precipitous decline in viewership prior to 2008, and its regular audience remained consistently around 30% of the population across the three election cycles, then falling in 2017 to 26%. Cable TV news’ popularity declined somewhat from around 40% in 2008 and 2012 to 31% in 2016 and 28% in 2017. Like network news, local TV news has dropped in popularity over the past two decades. This decline may in part be attributed to the disappearance of independent local news programs that have been replaced by shows operated by Sinclair Broadcast Group, a conservative media organization. At its peak, local news was viewed regularly by more than 70% of the population. Local news attracted the largest regular TV audience in 2008 (52%), dropped precipitously in 2012 (38%), climbed again in popularity in 2016 (46%), and fell to 37% in 2017 (Matsa, 2018).

In 2016, 57% of the public often got news on television compared to 38% who used online sources. From 2016 to 2017, television’s regular audience had declined to 50% of the population, and the online news audience had grown to 43%

In a relatively short period of time, the public’s preference for online news has made significant gains on television news as a main source. In 2016, 57% of the public often got news on television compared to 38% who used online sources. From 2016 to 2017, television’s regular audience had declined to 50% of the population, and the online news audience had grown to 43%. The nineteen-percentage point gap in favor of television news had closed to seven percentage points in a single year (Gottfried and Shearer, 2017). If current trends continue, online news may eclipse television news as the public’s main source in the not-so-distant future.

As the public’s preference for online news has surged, there has been a major decline in print newspaper readership. In 2008, 34% of the public regularly read a print paper. By 2012 the number had decreased to 23% and continued to fall to 20% in 2016 and 18% in 2017. Radio news has maintained a relatively stable audience share with occasional peaks when political news is especially compelling, such as during the 2008 presidential campaign when 35% of the public regularly tuned in. The radio news audience has remained at around 25% of the public since 2012. Talk radio, bolstered by the popularity of conservative hosts, such as Rush Limbaugh, and community radio reporting on local affairs consistently attracts around 10% to 12% of the population (Guo, 2015).

Social Media as a News Source

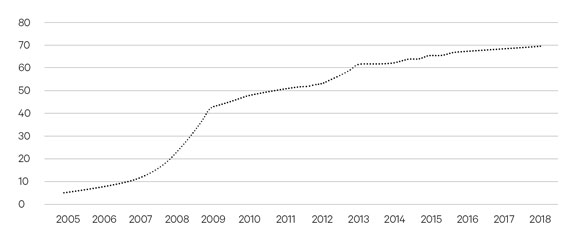

The American public’s use of social media increased rapidly in the period following the 2008 presidential election. Reliance on social media for news and political information has increased steadily over the past decade. According to the Pew Research Center, 68% of American adults in 2018 got news from social media at least occasionally, and 20% relied often on social media for news (Shearer and Matsa, 2018). Table 2 presents data from the Pew Research Center indicating the percentage of Americans who regularly used at least one social-media site like Facebook, Twitter, or LinkedIn over time. Few people were active on social media between 2005 and 2008. Even during the watershed 2008 campaign, only 21% of the public was on social media. By 2009, however, the number of people online had spiked to 42% as social media took hold in the political sphere in the run-up to the 2010 midterm elections. The Tea Party, a loosely-organized populist movement that ran candidates who successfully attained office, relied heavily on social media as an alternative to the mainstream press which they regularly assailed. The mainstream press was compelled to cover the Tea Party’s social-media pronouncements, which helped digital platforms to gain in popularity among voters. Social-media users who remained loyal to the Tea Party were prominent among supporters who actively worked on behalf of Donald Trump’s campaign by mobilizing voters in their networks (Rohlinger and Bunnage, 2017). By 2013, over 60% of the public was using social media. The percentage of social-media users has leveled off at near 70% since the 2016 presidential election.

Table 2. Americans’ social-media use 2005–18. (Source: Pew Research Center, Social-Media Fact Sheet, 2018.)

The shift in the public’s media allegiances toward digital sources has rendered social media a far more viable and effective political tool. A decade ago, only the most interested and tech-savvy citizens used social media for politics. Young people were advantaged in their ability to leverage social media due to their facility with the technology and their fascination with the novelty of this approach to politics. The age gap in political social-media use has been closing, as have differences based on other demographic characteristics, such as gender, race, education, and income (Smith and Anderson, 2018), which has altered politicians’ approach to these platforms. In the past, elites employed social media primarily to set the agenda for mainstream media so that their messages could gain widespread attention. Today, political leaders not only engage social media to control the press agenda, they can also use these platforms effectively to cultivate their political base. In addition, elites use social media to communicate with one another in a public forum. In 2017, Donald Trump and North Korean president Kim Jong Un traded Twitter barbs that escalated tensions between the two nations over nuclear weapons. They exchanged personal insults, with Trump calling Kim “little rocket man” and Kim labeling Trump a “dotard” and “old lunatic.” Trump also engaged in a bitter Twitter battle with French President Emmanuel Macron and Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau about tariffs and trade that prompted the American president to leave the G7 summit early in 2018 (Liptak, Kosinski, and Diamond, 2018).

The Political Twitterverse

The emergence of the political “Twitterverse” has coincided with the rise of social media over the past decade. Social media are distinct from other digital channels in that they host interactions among users who set up personal profiles and communicate with others in their networks (Carr and Hayes, 2015). Participants use social media to create and distribute content, consume and interact with material posted by their connections, and share their views publicly (Ellison and Boyd, 2013). Social-networking sites can help people to maintain and develop social relationships, engage in social surveillance and voyeurism, and pursue self-promotion (Alhabash and Ma, 2017). Users often employ social media to seek out and follow like-minded people and groups which promotes social bonding, reinforces personal and political identities, and provides digital companionship (Jung and Sundar, 2016; Joinson, 2008). These characteristics are highly conducive to the adaptation of social media—especially Twitter—for political use. Donald Trump’s Twitter followers identify with him on a personal level, which encourages their blanket acceptance of his policies (Owen, 2018).

Origins of Social Media

The current era of networked communication originated with the invention of the World Wide Web in 1991, and the development of Weblogs, list-serves, and e-mail that supported online communities. The first social-media site, Six Degrees, was developed in 1997 and disappeared in 2000 as there were too few users to sustain it. Niche sites catering to identity groups, such as Asian Avenue, friendship circles, including Friendster and MySpace, professional contacts, like LinkedIn, and public-policy advocates, such as MoveOn, also emerged in the late 1990s and early 2000s. The advent of Web 2.0 in the mid-2000s, with its emphasis on participatory, user-centric, collaborative platforms, coincided with the development of enduring social-media platforms, including Facebook (2004) and YouTube (2005) (van Dijck, 2013; Edosomwan et al., 2011), which have become staples of political campaigning, organizing, and governing.

When Twitter was founded in 2006, it was envisioned as a microblogging site where groups of friends could send short messages (tweets) to their friends about what was happening in their lives in real time in a manner akin to texting. Users could also upload photos, GIFs, and short videos to the site. Twitter initially imposed a 140-character constraint on tweets which was the limit that mobile carriers placed on SMS text messages. The limit was increased to 280 characters in 2017 as the popularity of the platform peaked and wireless carrier restrictions on the amount of content users could send were no longer relevant. Users easily circumvent the character limit by posting multiple tweets in sequence, a practice used frequently by Donald Trump. Twitter’s user base quickly sought to expand the functionality of the platform by including the @ symbol before a username to identify other users and adding #hashtags to mark content, making it easier to follow topics and themes. While the actual number of Twitter followers is difficult to verify as many accounts are dormant or controlled by bot software, it is estimated that there were 335 million active monthly users worldwide in 2018 (Statista, 2018). Still, it took Twitter twelve years to turn a profit for the first time when it increased attention to ad sales (Tsukayama, 2018).

Twitter in the Age of Trump

Standard communication practices for American politicians have been upended by Donald Trump’s use of Twitter. Trump was on Twitter seven years prior to his quest for the presidency. His signature Twitter style was established during his days on the reality TV program The Apprentice, and it has changed little since he launched his political career. Trump’s Twitter pronouncements are superficial, which is well-suited to a medium with a word limit on posts. His messages are expressed conversationally using an accessible, informal, fourth-grade vocabulary. Trump’s tweets have the tone of a pitchman who is trying to sell a bill of goods (Grieve and Clarke, 2017; Clarke and Grieve, 2017). They are often conflicting, confusing, and unclear, which allows users to interpret them based on their own preconceptions. His posts are repetitious and have a similar cadence which fosters a sense of believability and familiarity among his loyalists (Graham, 2018).

Social-media users often employ social media to seek out and follow like-minded people and groups which promotes social bonding, reinforces personal and political identities, and provides digital companionship

Trump has bragged that his control over Twitter paved his path to the White House (Tatum, 2017). As a presidential candidate, Trump effectively engaged Twitter to publicize his thoughts, attack his long list of enemies, and hijack political discourse. His supporters became ardent followers of his Twitter messages during the campaign. Trump’s campaign social-media style contrasted with Hillary Clinton’s more controlled approach, which had been the pre-Trump norm (Enli, 2017). Clinton’s social-media posts were measured in tone, rarely made personal attacks, and provided reasons and facts supporting her issue positions. In contrast, Trump made broad, general declarations that lacked evidence (Stromer-Galley, 2016) and claimed credit for the accomplishments of others (Tsur et al., 2016).

Since the election, Twitter has become Trump’s connection to the world outside the White House. He engages in “rule by tweet,” as his Twitter feed substitutes for regular presidential press conferences and weekly radio addresses that were the norm for his predecessors when making major policy announcements. Trump regularly produces nasty and outlandish tweets to ensure that he remains at the center of attention, even as political and natural disasters move the spotlight. Twitter changes the life cycle of news as developing reports can be readily overtaken by a new story generated by a provocative tweet. A digital communications strategist for the Trump campaign named Cassidy asserted that this strategy has been intentional: “Trump’s goal from the beginning of his candidacy has been to set the agenda of the media. His strategy is to keep things moving so fast, to talk so loudly—literally and metaphorically—that the media, and the people, can’t keep up” (Woolley and Guilbeault, 2017: 4). Trump’s Twitter tirades often sideline public discussions of important policy issues, such as immigration and health care, distract from embarrassing personal scandals, and attempt to camouflage the mishaps of his administration.

Amplification, Incivility, and Polarization

The power of social media to influence politics is enhanced due to their ability to amplify messages quickly through diverse media platforms. Social media have become a steady source of political content for news outlets with large audiences, especially cable news. Trump supporters regularly tune in to Fox News to cheer his latest Twitter exploits. Talking heads on media that view Trump more negatively, like CNN and MSNBC, spend countless hours attempting to interpret his tweets as the messages are displayed prominently on screen. Supporters who interact with, annotate, and forward his messages lend greater credence to Trump’s missives within their networks. Trump’s individual messages are retweeted 20,000 times on average; some of his anti-media screeds have been retweeted as many as 50,000 times (Wallsten, 2018). The perception that Trump is powerful is enhanced simply by virtue of the amount of attention he draws. Politicians can use the amplification power of social media to galvanize public opinion and to call people to action. These benefits of Twitter amplification have been shown to empower men substantially more than women. Male political journalists have a greater audience on Twitter than their female peers, and they are more likely to spread the political messages of men than women (Usher, Holcomb, and Littman, 2018).

The power of social media to influence politics is enhanced due to their ability to amplify messages quickly through diverse media platforms. Social media have become a steady source of political content for news outlets with large audiences, especially cable news

Social media host discourse that is increasingly incivil and politically polarizing. Offhanded remarks are now released into the public domain where they can have widespread political consequences (van Dijck, 2013). Trump’s aggressive Twitter pronouncements are devoid of filtering that conforms to cultural codes of decency. He makes expansive use of adjectives, typically to describe himself in positive terms and to denigrate others. He constantly refers to himself as “beautiful,” “great,” “smartest,” “most successful,” and “having the biggest brain.” In contrast, he refers to those who fall out of favor as “lying Hillary Clinton,” “untruthful slime ball James Comey” (a former FBI director), and “crazy Mika” (Brzezinski, a political talk-show host). As of June 2018, Trump had used the terms “loser” 246 times, “dummy” 232 times, and “stupid” 192 times during his presidency to describe people he dislikes (Armstrong, 2018).

Politicians have engaged in partisan Twitter wars that have further divided Republicans and Democrats, conservatives and liberals. On a day when the New York Times revealed that the Trump family had dodged millions of dollars in taxes and provided Donald Trump with far more financial support than he has claimed, Trump sought to shift the press agenda by tweeting his anger at “the vicious and despicable way Democrats are treating [Supreme Court nominee] Brett Kavanaugh!” Research conducted at the University of Pennsylvania found that the political use of Twitter by the general public is concentrated among a small subset of the public representing polar ideological extremes who identify as either “very conservative” or “very liberal.” Moderate political voices are rarely represented on the platform (Preotiuc-Pietro et al., 2017).

The Twitterverse is highly prone to deception. Twitter and other social media have contributed to—even fostered—the proliferation of false information and hoaxes where stories are entirely fabricated. False facts spread fast through social media. They can make their way onto legitimate news platforms and are difficult to rebut as the public has a hard time determining fact from fiction. Many people have inadvertently passed on “fake news” through their social-media feeds. In fact, an MIT study found that people are more likely to pass on false stories through their networks because they are often novel and generate emotional responses in readers (Vosoughi, Roy, and Aral, 2018). President Barack Obama has referred to the confusion caused by conspiracy theories and misleading information during the 2016 election as a “dust cloud of nonsense” (Heath, 2016).

Misinformation is often targeted at ideological audiences, which contributes the rise in political polarization. A BuzzFeed News analysis found that three prominent right-wing Facebook pages published misinformation 38% of the time and three major left-wing pages posted false facts 20% of the time (Silverman et al., 2016). The situation is even more severe for Twitter, where people can be completely anonymous and millions of automated bots and fake accounts have flooded the network with tweets and retweets. These bots have quickly outrun the spam detectors that Twitter has installed (Manjoo, 2017).

Trump supporters regularly tune in to Fox News to cheer his latest Twitter exploits. Talking heads on media that view Trump more negatively, like CNN and MSNBC, spend countless hours attempting to interpret his tweets as the messages are displayed prominently on screen

The dissemination of false information through Twitter is especially momentous amidst the uncertainty of an unfolding crisis where lies can spread much faster than the truth (Vosoughi, Roy, and Aral, 2018). Misinformation and hoaxes circulated widely as the shooting of seventeen students at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland Florida in February of 2018 was unfolding. Conspiracy theories about the identity of the shooter pointed in the wrong direction. False photos of the suspect and victims were circulated. Tweets from a reporter with the Miami Herald were doctored and retweeted to make it appear as if she had asked students for photos and videos of dead bodies. Within an hour of the shooting, Twitter accounts populated by Russian bots circulated hundreds of posts about the hot-button issue of gun control designed to generate political divisiveness (Frenkel and Wakabayaski, 2018). In the weeks after the shooting, as Parkland students became activists for stronger gun control measures, conspiracy theories proliferated. A widespread rumor asserted that the students were “crisis actors” who had no affiliation with the school. A doctored conspiracy video attacking the students was posted on YouTube and became a top trending clip on the site (Arkin and Popken, 2018).

The Emergence of News Deserts

The consequences of the rise of social media and the spread of false information have been elevated by the disappearance of trusted local news organizations from the media landscape. The proliferation of “news deserts”—communities where there are no responsible local news organizations to provide information to residents and to counter false stories—has meant that misinformation is often taken for fact and spread virally through people’s social networks unchecked (Bucay et al., 2017). Facebook and Twitter have been reluctant to deal effectively with the flow of misinformation through their platforms and have even refused to remove demonstrated false stories from their sites (Hautala, 2018). In 2018, Facebook, Twitter, Apple, and YouTube permanently banned alt-right radio host Alex Jones and his site, InfoWars, after failing to take any disciplinary action for years against his prolific spread of abusive conspiracy theories. But this move by big media companies was an exception. These circumstances have raised the potential for misinformation to unsettle the political system.

The proliferation of “news deserts”—communities where there are no responsible local news organizations to provide information to residents and to counter false stories—has meant that misinformation is often taken for fact and spread virally through people’s social networks

Local news historically has been a staple of Americans’ media diets. Less than a decade ago, local newspapers were responsible for approximately 85% of fact-based and investigative news (Jones, 2011). However, their importance for informing and shaping opinions of people in small towns and suburban communities has often been underestimated. Community newspapers have been far more consequential to their millions of readers than large newspapers of record, such as The New York Times and The Washington Post, whose stories are amplified on twenty-four-hour cable news programs. People tend to trust their local news outlets, and to have faith that the journalists—who are their neighbors—will report stories accurately. Citizens have relied heavily on local news outlets to keep them informed about current happenings and issues that are directly relevant to their daily lives. Local news stories influence the opinions of residents and routinely impact the policy decisions made by community leaders. Importantly, audiences rely on local journalists to provide them with the facts and to act as a check on misinformation that might be disseminated by outside sources, especially as they greatly distrust national news (Abernathy, 2016).

Trump’s tweets have become more relevant to his base in an era when local news sources have been disappearing from the media landscape. His tweets can substitute for news among people living in news deserts. The influence of his social-media messaging is enhanced in places where access to local media that would check his facts, provide context for his posts, and offer alternative interpretations is lacking The dearth of robust local news outlets is especially pronounced in rural, predominantly white areas of the country where Donald Trump’s political base is ensconced (Lawless and Hayes, 2018; Center for Innovation and Sustainability in Local Media, 2017). With the counterbalance of trusted local news sources, Trump’s attacks on the mainstream media resonate strongly, and the public’s political perspective is heavily influenced by relentless partisan social-media messages that masquerade as news in their feed (Musgrave and Nussbaum, 2018).

The concentration of media ownership in the hands of large corporations has further undermined truly local news. As independent media organizations have disappeared, they have been replaced in an increasing number of markets by platforms owned by news conglomerates. Sinclair Broadcast Group is the largest television news conglomerate in the United States and has bought out local stations across the country, including in news deserts. The company has strong ties to the Trump administration and has pushed its reporters to give stories a more conservative slant. An Emory University study revealed that Sinclair’s TV news stations have shifted coverage away from local news to focus on national stories, and that coverage has a decidedly right-wing ideological perspective (Martin and McCrain, 2018). On a single day, Sinclair compelled their local news anchors to give the same speech warning about the dangers of “fake news,” and stating that they were committed to fair reporting. Many anchors were uncomfortable making the speech, which they described as a “forced read.” A video of anchors across the country reciting the script was widely reported in the mainstream press and went viral on social media (Fortin and Bromwich, 2018).

The Future

The digital revolution has unfolded more rapidly and has had broader, deeper, and more transformative repercussions on politics and news than any prior transition in communication technology, including the advent of television. Over the past decade, the rise in social media as a political tool has fundamentally changed the relationships between politicians, the press, and the public. The interjection of Donald Trump into the political media mix has hastened the evolution of the media system in some unanticipated directions. As one scholar has noted: “The Internet reacted and adapted to the introduction of the Trump campaign like an ecosystem welcoming a new and foreign species. His candidacy triggered new strategies and promoted established Internet forces” (Persily, 2017).

The political media ecology continues to evolve. Politicians are constantly seeking alternatives to social media as a dominant form of communicating to the public. Candidates in the 2018 midterm elections turned to text messages as a campaign tool that is supplanting phone-banks and door-to-door canvassing as a way of reaching voters. New developments in software, such as Hustle, Relay, and RumbleUp, have made it possible to send thousands of texts per hour without violating federal laws that prohibit robo-texting—sending messages in bulk. Texts are used to register voters, organize campaign events, fundraise, and advertise. The text messages are sent by volunteers who then answer responses from recipients. The strategy is aimed especially at reaching voters in rural areas and young people from whom texting is the preferred method of digital communication (Ingram, 2018). Much like Trump’s Twitter feed, texting gives the perception that politicians are reaching out personally to their constituents. The tactic also allows politicians to distance themselves from big media companies, like Facebook and Google, and the accompanying concerns that personal data will be shared without consent.

The digital revolution has unfolded more rapidly and has had broader, deeper, and more transformative repercussions on politics and news than any prior transition in communication technology, including the advent of television

Great uncertainly surrounds the future of political communication. The foregoing discussion has highlighted some bleak trends in the present state of political communication. Political polarization has rendered reasoned judgment and compromise obsolete. The rampant spread of misinformation impedes responsible decision-making. The possibility for political leaders to negatively exploit the power of social media has been realized.

At the same time, pendulums do shift, and there are positive characteristics of the new media era that may prevail. Digital media have vastly increased the potential for political information to reach even the most disinterested citizens. Attention to the 2018 midterm elections was inordinately high, and the ability for citizens to express themselves openly through social media has contributed to this engagement. Issues and events that might be outside the purview of mainstream journalists can be brought to prominence by ordinary citizens. Social media has kept the #MeToo movement alive as women continue to tell their stories and form online communities. Further, there is evidence of a resurgence in investigative journalism that is fueled, in part, by access to vast digital resources available for researching stories, including government archives and big data analysis. These trends offer a spark of hope for the future of political media.

Bibliography

—Abernathy, Penelope Muse. 2016. The Rise of a New Media Baron and the Emerging Threat of News Deserts. Research Report. Chapel Hill, NC: The Center for Innovation and Sustainability in Local Media, School of Media and Journalism, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

—Alhabash, Saleem, and Ma, Mangyan. 2017. “A tale of four platforms: Motivations and uses of Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and Snapchat among college students?” Social Media and Society, January-March: 1–13.

—Arkin and Popken, 2018. “How the Internet’s conspiracy theorists turned Parkland students into ‘crisis actors’.” NBC News, February 21. https://www.nbcnews.com/news/us-news/how-internet-s-conspiracy-theorists-turned-parkland-students-crisis-actors-n849921.

—Armstrong, Martin. 2018. “Trump’s favorite Twitter insults.” Statista, June 28. https://www.statista.com/chart/14474/trump-favorite-twitter-insults/.

—Bimber, Bruce. 2014. “Digital media in the Obama campaigns of 2008 and 2012: Adaptation to the personalized political communication environment.” Journal of Information Technology & Politics 11(2): 130–150.

—Bucay, Yemile, Elliott, Vitoria, Kamin, Jennie, and Park, Andrea. 2017. “America’s growing news deserts.” Columbia Journalism Review, spring. https://www.cjr.org/local_news/american-news-deserts-donuts-local.php.

—Carr, Caleb T., and Hayes, Rebecca, 2015. “Social media: Defining, developing, and divining.” Atlantic Journal of Communication 23(1): 46–65.

—Center for Innovation and Sustainability in Local Media. 2017. Thwarting the Emergence of News Deserts. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina School of Media and Journalism. https://www.cislm.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/04/Symposium-Leave-Behind-0404finalweb.pdf.

—Clarke, Isobelle, and Grieve, Jack. 2017. “Dimensions of abusive language on Twitter.” In Proceedings of the First Workshop on Abusive Language Online. Vancouver, Canada: The Association of Computational Linguistics, 1–10. http://www.aclweb.org/anthology/W17-3001.

—Davis, Richard, and Owen, Diana. 1998. New Media in American Politics. New York: Oxford University Press.

—Edosomwan, Simeon, Prakasan, Sitalaskshmi Kalangot, Kouame, Doriane, Watson, Jonelle, and Seymour, Tom. 2011. “The history of social media and its impact on business.” The Journal of Applied Management and Entrepreneurship 16(3). https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Simeon_Edosomwan/publication/303216233_The_history_of_social_media_and_its_impact_on_business/links/57fe90ef08ae56fae5f23f1d/The-history-of-social-media-and-its-impact-on-business.pdf.

—Ellison, Nicole B., and Boyd, Danah. 2013. “Sociality through social network sites.” In The Oxford Handbook of Internet Studies, William H. Dutton (ed.). Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 151–172.

—Enli, Gunn. 2017. “Twitter as arena for the authentic outsider: Exploring the social media campaigns of Trump and Clinton in the 2016 US presidential election.” European Journal of Communication 32(1): 50–61.

—Fortin, Jacey, and Bromwich, Jonah Engel. 2018. “Sinclair made dozens of local news anchors recite the same script.” The New York Times, April 2. https://www.nytimes.com/2018/04/02/business/media/sinclair-news-anchors-script.html.

—Frenkel, Sheera, and Wakabayashi, Daisuke. 2018. “After Florida school shooting, Russian ‘bot’ army pounced.” The New York Times, February 2. https://www.nytimes.com/2018/02/19/technology/russian-bots-school-shooting.html.

—Gottfried, Jeffrey, and Shearer, Elisa. 2017. “Americans’ online news use is closing in on TV news use.” Fact Tank. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center. http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2017/09/07/americans-online-news-use-vs-tv-news-use/.

—Gottfried, Jeffrey, and Barthel, Michael. 2018. “Almost seven-in-ten Americans have news fatigue, more among Republicans.” Washington, DC: Pew Research Center. http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2018/06/05/almost-seven-in-ten-americans-have-news-fatigue-more-among-republicans/.

—Graham, David A. 2018. “The gap between Trump’s tweets and reality.” The Atlantic, April 2. https://www.theatlantic.com/politics/archive/2018/04/the-world-according-to-trump/557033/.

—Grieve, Jack, and Clarke, Isobelle. 2017. “Stylistic variation in the @realDonaldTrump Twitter account and the stylistic typicality of the pled tweet.” Research Report. University of Birmingham, UK. http://rpubs.com/jwgrieve/340342.

—Guo, Lei. 2015. “Exploring the link between community radio and the community: A study of audience participation in alternative media practices.” Communication, Culture, and Critique 10(1). https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/cccr.12141.

—Hautala, Laura. 2018. “Facebook’s fight against fake news remains a bit of a mystery.” c/net, July 24. https://www.cnet.com/news/facebook-says-misinformation-is-a-problem-but-wont-say-how-big/.

—Heath, Alex. 2016. “OBAMA: Fake news on Facebook is creating a ‘dust cloud of nonsense.’” Business Insider, November 7. https://www.businessinsider.com/obama-fake-news-facebook-creates-dust-cloud-of-nonsense-2016-11.

—Hindman, Matthew. 2018. The Internet Trap: How the Digital Economy Builds Monopolies and Undermines Democracy. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

—Ingram, David. 2018. “Pocket partisans: Campaigns use text messages to add a personal touch.” NBC News, October 3. https://www.nbcnews.com/tech/tech-news/sofas-ipads-campaign-workers-use-text-messages-reach-midterm-voters-n915786.

—Joinson, Adam N. 2008. “‘Looking at,’ ‘looking up’ or ‘keeping up with’ people? Motives and uses of Facebook.” Proceedings of the 26th Annual SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems. Florence, Italy, April 5–10: 1027–1036.

—Jones, Alex S. 2011. Losing the News: The Future of the News that Feeds Democracy. New York: Oxford University Press.

—Jost, John T., Barberá, Pablo, Bonneau, Richard, Langer, Melanie, Metzger, Megan, Nagler, Jonathan, Sterling, Joanna, and Tucker, Joshua A. 2018. “How social media facilitates political protest: Information, motivation, and social networks.” Political Psychology 39(51). https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/pops.12478.

—Jung, Eun Hwa, Sundar, Shyam S. 2016. “Senior citizens on Facebook: How do they interact and why?” Computers in Human Behavior 61: 27–35.

—Lawless, Jennifer, and Hayes, Danny. 2018. “As local news goes, so goes citizen engagement: Media, knowledge, and participation in U.S. House elections.” Journal of Politics 77(2): 447–462.

—Liptak, Kevin, Kosinski, Michelle, and Diamond, Jeremy. 2018. “Trump to skip climate portion of G7 after Twitter spat with Macron and Trudeau.” CNN June 8. https://www.cnn.com/2018/06/07/politics/trump-g7-canada/index.html.

—Manjoo, Farhad. 2017. “How Twitter is being gamed to feed misinformation.” The New York Times, May 31. https://www.nytimes.com/2017/05/31/technology/how-twitter-is-being-gamed-to-feed-misinformation.html.

—Martin, Gregory J., and McCrain, Josh. 2018. “Local news and national politics.” Research Paper. Atlanta, Georgia: Emory University. http://joshuamccrain.com/localnews.pdf.

—Matsa, Katerina Eva. 2018. “Fewer Americans rely on TV news: What type they watch varies by who they are.” Washington, DC: Pew Research Center, January 5. http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2018/01/05/fewer-americans-rely-on-tv-news-what-type-they-watch-varies-by-who-they-are/.

—Musgrave, Shawn, and Nussbaum, Matthew. 2018. “Trump thrives in areas that lack traditional news outlets.” Politico, March 8. https://www.politico.com/story/2018/04/08/news-subscriptions-decline-donald-trump-voters-505605.

—Owen, Diana. 2017a. “The new media’s role in politics.” In The Age of Perplexity: Rethinking the World We Know, Fernando Gutiérrez Junquera (ed.). London: Penguin Random House.

—Owen, Diana. 2017b. “Tipping the balance of power in elections? Voters’ engagement in the digital campaign.” In The Internet and the 2016 Presidential Campaign, Terri Towner and Jody Baumgartner (eds.). New York: Lexington Books, 151–177.

—Owen, Diana. 2018. “Trump supporters’ use of social media and political engagement.” Paper prepared for presentation at the Annual Meeting of the American Political Science Association, August 30–September 2.

—Persily, Nathaniel. 2017. “Can democracy survive the Internet?” Journal of Democracy 28(2): 63–76.

—Pew Research Center. 2018. “Social media fact sheet: Social media use over time.” February 5, 2018. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center. http://www.pewinternet.org/fact-sheet/social-media/.

—Preotiuc-Pietro, Daniel, Hopkins, Daniel J., Liu, Ye, and Unger, Lyle. 2017. “Beyond binary labels: Political ideology prediction of Twitter users.” Proceedings of the 55th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics. Vancouver, Canada: Association for Computational Linguistics, 729–740. http://aclweb.org/anthology/P/P17/P17-1068.pdf.

—Rohlinger, Deana A., and Bunnage, Leslie. 2017. “Did the Tea Party movement fuel the Trump train? The role of social media in activist persistence and political change in the 21st century.” Social Media + Society 3(2). http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/2056305117706786.

—Sayej, Nadja. 2017. “Alyssa Milano on the #MeToo movement: ‘We’re not going to stand for it any more.’” The Guardian, December 1. https://www.theguardian.com/culture/2017/dec/01/alyssa-milano-mee-too-sexual-harassment-abuse.

—Shearer, Elisa, and Matsa, Katerina Eva. 2018. News Across Social Media Platforms 2018. Research Report. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center, September 10. http://www.journalism.org/2018/09/10/news-use-across-social-media-platforms-2018/.

—Silverman, Craig, Hall, Ellie, Strapagiel, Lauren, Singer-Vine, Jeremy, and Shaban, Hamza. 2016. “Hyperpartisan Facebook pages are publishing false and misleading information at an alarming rate.” BuzzFeed News, October 20. https://www.buzzfeednews.com/article/craigsilverman/partisan-fb-pages-analysis#.wdLRgawza.

—Smith, Aaron, and Anderson, Monica. 2018. Social Media Use in 2018. Research Report. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center. http://www.pewinternet.org/2018/03/01/social-media-use-in-2018/.

—Statista. 2018. “Number of monthly active Twitter users worldwide from 1st quarter 2018 (in millions).” https://www.statista.com/statistics/282087/number-of-monthly-active-twitter-users/.

—Stromer-Galley, Jennifer. 2016. Presidential Campaigning in the Internet Age. New York: Oxford University Press.

—Tatum, Sophie. 2017. “Trump on his tweets: ‘You have to keep people interested.” CNN Politics, October 21. https://www.cnn.com/2017/10/20/politics/donald-trump-fox-business-interview-twitter/index.html.

—Tsukayama, Hayley. 2018. “Why Twitter is now profitable for the first time.” The Washington Post, February 8. https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/the-switch/wp/2018/02/08/why-twitter-is-now-profitable-for-the-first-time-ever/?utm_term=.d22610b684af.

—Tsur, Oren, Ognyanova, Katherine, and Lazer, David. 2016. “The data behind Trump’s Twitter takeover.” Politico Magazine April 29. https://www.politico.com/magazine/story/2016/04/donald-trump-2016-twitter-takeover-213861.

—Usher, Nikki, Holcomb, Jesse, and Littman, Justin. 2018. “Twitter makes it worse: Political journalists, gendered echo chambers, and the amplification of gender bias.” International Journal of Press/Politics 1–21. http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/1940161218781254.

—Van Dijck, José. 2013. The Culture of Connectivity: A Critical History of Social Media. New York: Oxford University Press.

—Vosoughi, Soroush, Roy, Deb, and Aral, Sinan. 2018. “The spread of true and false news online.” Science 359(6380): 1146–1151.

—Wallsten, Kevin. 2010. “‘Yes We Can’: How online viewership, blog discussion, campaign statements, and mainstream media coverage produced a viral video phenomenon.” Journal of Information Technology and Politics 2(3): 163–181.

—Wallsten, Scott. 2018. “Do likes of Trump’s tweets predict his popularity?” Technology Policy Institute Blog, April 17. https://techpolicyinstitute.org/2018/04/17/do-likes-of-trumps-tweets-predict-his-popularity/.

—Woolley, Samuel C., and Guilbeault, Douglas R. 2017. “Computational propaganda in the United States of America: Manufacturing consensus online.” Working Paper No. 2017.5. Oxford Internet Institute: Computational Propaganda Research Project.

Comments on this publication