Latin America, like much of the developing world, will have to face serious challenges in the current century. Environmental changes, persistent inequality, and increasing violence force millions of people throughout the region to live in a constant state of uncertainty. Will Latin American countries be up to the task of finally improving the life of their inhabitants?

What are the grand challenges of the 21st Century for the world and specifically for Latin America? Of all the things going wrong, what should we be most worried about? In this essay, we begin by describing what we contend are the most critical global challenges, and then analyze how these will play out in the region that we are studying, Latin America.

The most obvious unravelling that we face is that of the environment. Because of global climate change, resource depletion, and general environmental destruction, the rules that have governed our planet, and which have been the underlying basis of our society, are changing faster than we can appreciate, with consequences we cannot imagine. Results could be as dramatic as flooded cities or as trivial as increased turbulence on transoceanic flights. Highly populated areas of the world will become possibly uninhabitable and the resources on which modernity depends will become rarer and more expensive. Conflict may become more and more fueled by scarcity, and our ability to cooperate globally curtailed by an impulse to find solace within the smaller tribe. As we reach various tipping points, the question is no longer how to stop climate change, but how to adjust to new rules and limits.

While it might not make for as exciting a screenplay, the modern world also has to fear man-made risks in other forms. Today, practically every human is somehow dependent on the continued flow of money, goods, culture, and people that we collectively call globalization. This process has brought about unimaginable abundance for many, but with tremendous costs in terms of our global sense of community as well as to the environment. That plenty is also purchased with an ever-greater fragility of our basic systems of nutrition, finance, and energy. More than ever in the history of humanity, we depend on other distant parts of the world to do their part, whether it is producing the food we eat, running the ships in which it travels with expensive refrigeration, and accepting some form of global payment that keeps the machine flowing. But no machine is perfect. As we make our systems more complex and we link each part tighter, we become subject to the possibility of the very web unraveling and leaving us isolated unprepared for autarky.

Much of these systems depend on functioning institutions. In an interesting paradox, the globalized system depends more than ever on rules and organizations able to enforce them. Markets need states to safeguard them and this is as true in the 21st C. as it was in the 16th. The increased risk of environmental and public health catastrophes also makes the coordinating functions of state more evident. Levees will not build and maintain themselves. Private actors will not control epidemics through individual incentives. Even as they have lost some of their autonomy to global forces, states remain critical for assuring the delivery of services, for controlling violence, and for certifying personal identities. Yet contemporary states live in a paradox: as they are hemmed in by forces out of their control, the demands placed on them grow exponentially. So, as globalization re-distributes work and income throughout the world, citizens demand more protection from their governments. The question of “Who Rules?” remains critical for any social system, from the individual city to the global web.

Partly a product of globalization, partly the inheritance of 10,000 years of collective life, inequality has become an even greater problem for all societies. Inequality among societies is not only an ethical concern, but one that makes global cooperation on issues such as climate change very difficult. This inequity in turn produces a flow of human beings seeking better lives in areas where they might not be welcomed. Domestic inequality also makes governing even small territories difficult as the costs and benefits of rule are not evenly distributed. Inequality is a particular challenge because it is partly a matter of perception. Even if the past 50 years have seen a dramatic increase in life expectancy across the planet, they have also made the inequities among and within societies ever more visible. Furthermore, traditional mechanisms employed by national states by which societies abated inequality may be nowadays ineffective if not counterproductive.

We have built a style of life for many, but certainly not all.

Finally, while some claim that world has become much more peaceful, the form of violence has merely changed. Where 100 years ago, we thought of violence in terms of massive organized conflict, now it takes a less aggregated and perhaps less organized form. The origin of violence may no longer be dressed as an enemy combatant, but that makes him or her harder to identify and deal with threats. When rental trucks become weapons of mass death, how do you police ALL traffic? When the forces of order are outgunned, how do you guarantee some rule of law? With human interactions becoming global, with rapid cultural change taking place; how do we create and learn new rules and norms that mitigate everyday conflict?

Indeed, the world has much to be anxious about. We have built a style of life for many (but certainly not all) that rivals that of aristocrats of the 19th C. But, very much like them, we fear that the rules of the world are changing and we wonder how much change we can accept and how much of the status quo can (or should) be kept. With this perspective in mind, we will now discuss how these challenges are playing out in Latin America.

The Environment

We can divide the environmental challenges into those that are already apparent and those that will become more so through the 21st C. (World Bank, 2016) Among the former, the most obvious one is the pollution that mars many cities in Latin America. In many cases, this results not so much from industry as from the massive concentration in 1-2 urban areas in each country. This pollution can be both airborne, and arguably more important, also originates in the underdevelopment of sanitation infrastructure. In many Latin American cities, a quarter of the population has no access to potable water and developed sanitation and sewage. This remains a major public health hazard. The situation is becoming worse as droughts and their severity become more frequent and harsher. The changes in the precipitation are challenging what systems do exists by also introducing a variability that many of these systems cannot handle further eroding the quality of life or urban residents.

Away from the cities, deforestation and increases in temperature are also threatening the viability of communities. Deforestation continues to be a major problem throughout the region, but particularly in Brazil. Higher temperatures are also destroying the water systems of the Andes as they lead to disappearing glaciers. These higher temperatures are also associated with more frequent and more violent outbreaks of diseases.

For all of these, there is of course a great deal of variance in the region with the same pattern all over the globe: the poor and the marginal, whether urban or rural, suffer much more both measured from within and among levels of inequality. The poorest of the poor in Central America, for example, have the greatest danger of suffering from environmental challenges.

The continent is lucky in that the worst nightmare scenarios of global climate change are less relevant, with the obvious exception of Caribbean countries where rising sea levels represent an immediate problem. The changes in climate might also begin effecting the commodity basis of these countries’ economies. Soybeans, for example, are sensitive to both climate changes and variability as is cattle ranching. Fruits and fisheries would also be negatively affected by climate change. South America is rich in the one material that looms large in climate catastrophe scenarios. The continent accounts for roughly 25% of the worlds freshwater. Unfortunately, this is distributed very unevenly throughout the region. To the extent that water may become the prized commodity of the 21st C, the region will have yet another natural resource with which to bargain.

In general, Latin America may be spared some of the more nightmarish scenarios foreseen for Africa and much of southern Asia. However the risk of climate change cannot be measured purely by exposure, but also by the robustness of institutions to deal with it. Here, the region with its high urban concentrations and weak governance structures may have to deal with many more consequences than the purely organic models might predict.

Human Systemic Risk

The natural environment is not the only threatened “eco-system” in the 21st C. Increasingly the world is connected through transfers of humans, merchandise, capital, and culture. More importantly, even the poorest nations are dependent on the continued flow through the global infrastructure, but a country’s dependence on the global web is highly correlated with its level of development (Centeno et al, 2015; World Bank 2017). Increasingly, we will need some indices that quantify dependence on the global web by domain and also location of origins and destinations. So, for example, most of Western Europe and East Asia is more tightly dependent on the continued flow of goods (especially food and fuel) than is the United States.

On the one hand, the region is in much better shape than most others around the globe. It certainly has the potential to “live off” its own resources. A breakdown in the global supply and demand would not leave the region permanently starving and thirsty. Because of its relatively marginal position in the world’s production chain, the region does not depend on complex trade flows to maintain its economy to the extent of East Asia or Western Europe. Among the middle-income economies, Latin America is distinguished by the relatively low percentage of GDP accounted for by trade (with Mexico being a prominent exception).

That apparent robustness, however, masks a structural fragility. The position of the region in the global trade system remains practically the same as it was in the 19th Century. With the exception of Mexico, every country’s economy relies on the production of a small number of commodity products for export. While Brazil may highlight its production of Embraer jets, its foreign trade is still largely based on products with soybean, for example, accounting for nearly 1/10th of total trade. The situation in Argentina and Peru is even worse. In a paradox that theorists of dependency theory would not find surprising, the region as a whole exports a significant amount of crude oil, but is increasingly dependent on imports of refined gasoline. Similar stories can be told of a myriad of industrial and chemical products.

Inequality is a historical stigma, constantly visible, throughout all countries in the region.

Remittances are another form of dependence on a continuing global system and these remain an important part of the economies of several countries. These are economies whose engagement in global trade is largely an exchange of human labor for wages in another currency. A breakdown in the flow of people and /or the flow of money would be devastating for many countries, and especially the Caribbean and Central America where this can represent up to 1/6th of GDP.

It is not only products that define the region’s dependency. China and the United States represent an outsized share of the export markets in the region. Disruption in either of these political economies or breakdowns in the global trade infrastructure would severely constrain the delivery of exports and imports.

Inequality

It seems historically inaccurate to single out inequality as one of the challenges Latin America faces towards the future. Inequality is a historical stigma, constantly visible, throughout all countries in the region. Why is inequality a defining characteristic of Latin America? One possible answer is that economic inequality is a self-reinforcing phenomenon that cannot be separated from its political consequences. As countries become more unequal, the political institutions they develop and the relative strength of different political actors might make economic inequality more durable. Modern Latin America was early on set on a path of inequality, and it has mostly been faithful to it. Therefore, the main challenge Latin America faces in terms of inequality might not be economic inequality per se but the capacity to keep access to political institutions broad and open enough so that the underprivileged can influence economic outcomes.

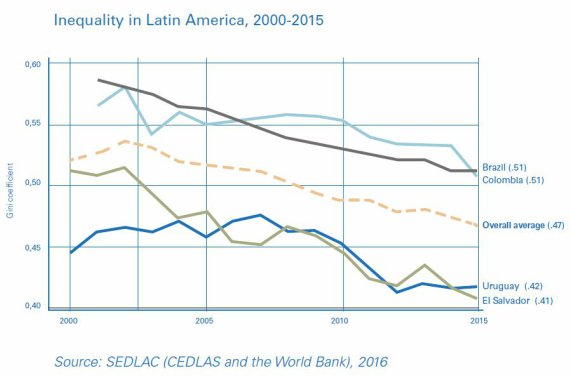

The last couple of decades in Latin America offer some hope on how inequality can be reduced, though it may not be enough to say that the region is set on a path that will finally make equality self-reinforcing. The 1990s was a decade where inequality increased overall in the region. The 2000s, however, achieved a rate of reduction in inequality unseen before (López-Calva&Lustig, 2010, see Figure 1). The establishment of cash-transfer programs explains in large part this important change, especially in the overall reduction of the GINI coefficient. In contrast to previous social policy in the region, these programs are targeted to the population with lowest incomes, thus achieving a direct impact on inequality by affecting the indicator we use to measure it: income. The most visible transfer programs because of their size and their measured impact were Oportunidades in Mexico, and Bolsa Familia in Brazil. However, similar programs were implemented in other countries throughout the region. Also, excluding important cases like Mexico, minimum wages were raised in most of the region during the same period, again affecting directly the income of the poorest.

It is hard not to associate the reduction of inequality in Latin America with the election of left-wing governments in the early years of the current century (Huber, 2009). The establishment of democracy not only brought more stable political institutions, and less political violence, it also brought the opportunity for segments of the population that had been historically underrepresented to finally influence policy decisions. The cases of Bolivia with the election of Evo Morales, the Frente Amplio governments in Uruguay, the center-left coalition in

Chile and the PT in Brazil are some of the most prominent examples. However, stable organizations that substantially represent the underprivileged like labor unions are either weak or due to the historical exclusion of informal workers tend to represent another source of privilege, not of equalization.

The diminishing rate in the reduction of inequality for the 2010s is a bitter reminder that the relevant characteristic of the region is not only the prevalence of inequality, but also its durability. Even though cash-transfer programs may have put a dent in it, their effect is limited by the fact that after their initial success further coverage can only be marginal and increasing the value of the transfers might put too much pressure on public finances, as economists throughout the region have argued (Gasparini, 2016). This is especially true now since the ability of many Latin American countries to keep rates of economic growth stable has been put into question in the last couple of years. Furthermore, even though economic inequality is a highly visible aspect of inequality, and one that is constantly measured, it only illustrates indirectly other aspects of inequality. Stark differences in the quality and access to public goods like a healthy environment, comfortable housing, and other aspects that determine our overall quality of life might be even more important that just income inequality. As it is well known, Latin America is still highly unequal in all these other aspects.

The combination of slower economic growth and persistent inequality is a source of anxiety for all political actors in the region. The political effect on the stabilization of inequality cannot be underestimated. People are directly affected by differences in income in terms of lifetime outcomes. However their perception of fairness and justice are also strongly linked to levels of inequality. Negative perceptions regarding the fairness of society are a source of anxiety for economic elites. They worry that populist politicians might come into office and wreak havoc to economic stability. At the same time, leftist parties and politicians worry that economic elites and international financial institutions will overreact to demands of redistribution by curtailing the ability of the underprivileged to influence policy. This anxiety filled context may lead to situations such as the current political turmoil in Brazil which should be a cautionary note for the rest of the region.

Violence

There are two main challenges that Latin America currently faces in regard to violence. The first one is an increase in interpersonal violence throughout the region; and the second one is violence linked to organized crime, especially in areas that are relevant for drug related markets. The latter type of violence is constantly made visible by the media and it has become a source of mano dura policies with little respect for human rights, whereas it is the former, interpersonal violence that claims more victims every year in countries across the region.

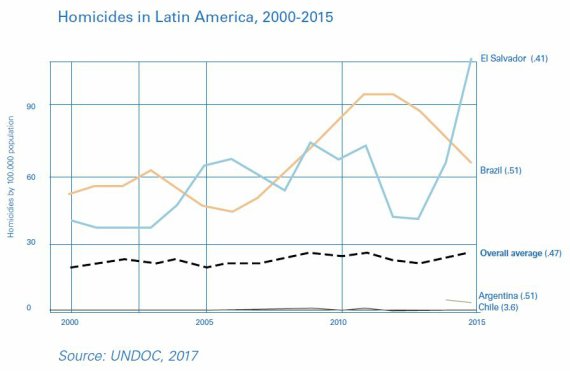

There is great variation in national homicide rates within Latin America, and there is even more variation within countries (see Figure 2). Some countries like Honduras and El Salvador share the highest levels of homicides around the world, whereas others like Chile and Uruguay are among the lowest. Larger countries like Mexico, Brazil, Colombia, and Venezuela have regions where their homicide rates are comparable to those of Scandinavian countries, while at the same time they have locations with levels of violence reminiscent of the American wild-west.

A large part of this variation is explained by social and demographic phenomena. The two characteristics that seem to be driving violence are demographic structures with bulges of young men, and an increasing participation of women in the labor market (Rivera, 2016). Though these large trends do not allow to pinpoint with precision the motivations behind increasing interpersonal violence, it is not farfetched to make the link between violence, changing family structures, weakened state institutions, and the increasing presence of unsupervised young men. This absence of supervision or social control, either by traditional social institutions—i.e. the family–or modern institutions—i.e. schools and hospitals–, might also be the basis for increasing gender based violence, and the creation of gangs which may become attached to illegal activities.

The other important source of variation is not drug production or trafficking per se, but how governments deal with illegal drug markets (Lessing, 2012).

There are some countries that are ranked as large producers of drug-related products, but have little violence linked to them. On the other hand, there are other countries with small drug markets, or with territories exclusively used as trafficking routes, where there are high levels of violence associated to these activities. Governments sometimes confront, sometimes appease, and sometimes simply turn a blind eye to drug trafficking; each policy option leading to divergent outcomes in terms of violence.

Overall, Latin America states have not been able to make economic activity predictable for most of the population.

Nonetheless, even if structural sources of violence play an important role in explaining insecurity in Latin America, the perception many people have is that the main source of violence and crime is impunity. Everyday life in most countries in the region goes on with the expectation that the authorities will not be able to intervene when a robbery or homicide is committed, and once it is committed the expectation is that victims will not receive much help. Furthermore, perpetrators will most likely not be punished or if they are punished this punishment will be attenuated by their relative economic or political power. Though there have been important changes in the last few decades regarding the independence of judicial institutions and civilian control over the coercive apparatus of the state, the focus on impunity has sometimes led to “mano dura” policies that increase the arbitrary use of violence by the authorities against civilians, disregards due process, and frames human rights as obstacles that favor criminals. Paradoxically these policies do not end up displaying the stronger rule of law they offer, but to the contrary they make evident the weakness of states that anxiously use violence precisely because they can’t control it. In this respect prospects are grim. Reflecting on the future, the region has to seriously reconsider the basic premises of what produces violence, and what controls it. It has to rethink both the role of the state and the role of society on what controls the use of violence in everyday life, and what exacerbates it.

State Capacity

By any standard measure, the Latin American state is weak and fragile. Perhaps the most obvious indicator is the size of the percentage of the economy accounted for by the state. Whether measured in terms of revenue or expenditure, the Latin American states are small and broadly ineffective. Chile and Costa Rica are prominent exceptions, but in general the Latin American state may be described as a “hollow Leviathan”.

Paradoxically, Latin American states do perform well in some of the functions associated with strong institutions. The region as a whole outperforms countries with similar wealth in providing some foundation of public health and educations.

But in others (and notably monopoly over the means of violence as described above) Latin American government institutions are widely perceived as inadequate. Infrastructure is one area where the region underperforms based on its wealth. This creates a permanent obstacle to more sophisticated forms of economic development and also takes a toll on citizens relying on transport and communication services. The delivery of some services such as postal and garbage collection is very bad and has often been absorbed by private sector firms.

One of the central questions that need to be asked regarding Latin America´s future is if the conditions that allow for a strengthening of states are present.

One indication of the relative weakness of the state is the size of the informal economy. While some may argue that this serves as an economic dynamism, it also means that the state has a difficult time taxing much of the economic activity and also fails to protect workers. The enforcement of contracts is also a problem, as confidence in the courts remains low. A similar story could be told of the public service in general where (with the exception of some islands of excellence such as Central Banks) standards are less than Weberian (Centeno et al., 2017). Corruption is a major problem and as in the case of Brazil over the past few years, a source not just of economic inefficiency, but a challenger to the legitimacy of government itself.

Thus, one of the central questions that need to be asked regarding Latin America’s future is if the conditions that allow for a strengthening of states are present. Some of these conditions are the product of the international context and some might be the product of domestic political coalitions. Therefore, the future is far from certain. On the one hand, it could be argued that increased and increasing globalization further diminishes the capacity of states to control fiscal policy, and thus redistribute wealth through services and social policy. On the other hand, rising globalization may allow for more opportunities for developing countries to turn commodity booms into sources of capitalization for local investment. Furthermore, criminal enterprises have expanded the access to international markets both as sellers (as in the case of drug-trafficking) and as buyers (as in the case of money laundering and arms), while international cooperation may allow for better coordination in the pursuit of transnational criminal organizations. The opportunities and restrictions globalization imposes on developing countries is a topic thoroughly discussed, though one aspect of it that receives little attention is the relative standing of national states vis-à-vis sub-national states and local political actors.

Conclusions

Many of the challenges facing Latin America in the 21st Century are ones with which it has dealt since independence from Spain 200 years ago. The dependence on fragile trade relationships and primary products, the incessant violence, and inequality practically defined the region in the 19th Century. The fragility of the environment and the global web are new, but the outstanding challenge remains the same: the institutionalization of social order through the state. While the region may not be able to resolve all the challenges it faces, nothing can be done without the solidification of state capacity. Some states in Latin America might be better than others with regards to their performance in terms of the provision of certain services, or the implementation of particular policies. However, the type of solidification in dire need is one the makes both state and society more regular and predictable. Everyday, Latin Americans makes use of their ingenuity in order to deal with the unexpected and irregular sources of violence, poverty, and environmental phenomena. However, individual ingenuity is costly when mostly directed at basic needs, and uncertainty has only increased with globalization and with the slow pace by which the world has met the challenge of human-made environmental changes.

Overall, Latin American states have not been able to make economic activity predictable for most of the population. Policies directed towards social inclusion have become less and less about building institutions that permanently help individuals deal with the uncertainties of the market, and more about providing minimal and intermittent relief to those in a situation of emergency. Likewise, most states throughout the region have not been able to control interpersonal violence and in some cases the state itself has become a source of increased violence. State action regarding basic social order instead of considering the structural sources of violence, is superficially interpreted as a “simple” problem of coercion. Paradoxically, this means that in a more uncertain world, instead of states becoming a source of stability and regularity, they have become an added source of uncertainty for everyday life. This paradox might be the greatest challenge Latin America has to face. Meeting the challenge implies that countries will need stronger states, not only for implementing specific policies, but more importantly for developing new ways to regularly deal with the increasing risks their populations are facing.

Bibliography

Centeno, Miguel A., Atul Kohli, and Deborah J. Yashar Eds. States in the Developing World. Cambridge ; New York, NY: Cambridge University Press, 2017.

Centeno, Miguel, M. Nag, TS Patterson, A. Shaver, A.J. Windawi. “The Emergence of Global Systemic Risk”. Annual Review of Sociology, 41, 65-85, 2015.

Gasparini, Leonardo, Guillermo Cruces, and Leopoldo Tornarolli. “Chronicle Of A Deceleration Foretold Income Inequality In Latin America In The 2010s.” Revista de Economía Mundial, no. 43 (2016): 25–45.

Huber, Evelyne. “Politics and Inequality in Latin America.” PS: Political Science&Politics 42, no. 4 (October 2009): 651–55.

Lessing, Benjamin. “When Business Gets Bloody: State Policy and Drug Violence.” In Small Arms Survey 2012: Moving Targets, 40–77. Small Arms Survey. Cambridge University Press, 2012.

López-Calva, Luis Felipe, and Nora Claudia Lustig, eds. Declining Inequality in Latin America: A Decade of Progress? 1st edition, Edition. Washington, D.C: Brookings Institution Press, 2010.

Rivera, Mauricio. “The Sources of Social Violence in Latin America: An Empirical Analysis of Homicide Rates, 1980–2010.” Journal of Peace Research 53, no. 1 (January 1, 2016): 84–99.

World Bank, “Its Time for Latin America to Adapt to Global Climate Change”, http://www.worldbank.org/en/news/feature/2016/07/18/america-latina-llego-hora-adaptarse-calentamiento-global 2016.

World Bank,World Development Report, Washington DC: World Bank, 2017.

Comments on this publication