Perhaps one of the most far-reaching developments of the last twenty years has to do with the rise of emerging economies, which once represented no more than 15% of the global economy and now have come to account for nearly 50% of economic activity. These economies are growing fast and are located around the world, including the BRICs (Brazil, Russia, India, and China), MITS (Mexico, Indonesia, Turkey, and South Africa), and many other economies in Africa, East Asia, South Asia, Latin America, and the Middle East. Some of these countries have become major exporters of manufactured goods while others sell agricultural, energy or mineral commodities. In the last few years, the emerging economies have also become major sources of foreign direct investment, that is, companies based in emerging economies have expanded throughout the world, making acquisitions and setting up manufacturing and distribution operations not just in emerging economies and developing countries but in developed ones as well, becoming Multinational Enterprises (MNEs).

The literature has referred to Emerging Market Multinationals in a variety of ways, including “third-world multinationals”,1 “latecomer firms”,2 “unconventional multinationals”,3 or “emerging multinationals”.4 In some cases, these firms are labeled according to their region of origin, using terms such as “dragon multinationals”,5 or “multilatinas”.6 We label them as “The New Multinationals”.7 They have become key actors in foreign direct investment and cross-border acquisitions.8

The proliferation of the new multinationals has taken observers, policymakers, and scholars by surprise. Many of these firms were marginal competitors just a decade ago; today they are challenging some of the world’s most accomplished and established multinationals in a wide variety of industries and markets. In this chapter we try to answer three fundamental types of questions. First, do these firms share some common distinctive features that distinguish them from the traditional MNEs? Second, what advantages have made it possible for them to operate and compete not only in host countries at the same or lower level of economic development but also in the richest economies? Third, how come they have been able to expand abroad at dizzying speed, in defiance of the conventional wisdom about the virtues of a staged, incremental approach to international expansion? Before being in a position to answer these questions, one must begin by outlining the established theory of the MNE and explore the extent to which its basic postulates need to be reexamined.

The Theory of the Multinational Firm

Although MNEs have existed for a very long time, scholars first attempted to understand the nature and drivers of their cross-border activities during the 1950s. The credit for providing the first comprehensive analysis of the MNE and of foreign direct investment goes to an economist, Stephen Hymer, who in his doctoral dissertation observed that the “control of the foreign enterprise is desired in order to remove competition between that foreign enterprise and enterprises in other countries. Or the control is desired in order to appropriate fully the returns on certain skills and abilities”.9 His key insight was that the multinational firm possesses certain kinds of proprietary advantages that set it apart from purely domestic firms, thus helping it overcome the “liability of foreignness.”

The multinational firm possesses certain kinds of proprietary advantages that set it apart from purely domestic firms

Multinational firms exist because certain economic conditions and proprietary advantages make it advisable and possible for them to profitably undertake production of a good or service in a foreign location. The most representative case of foreign direct investment is horizontal expansion, which occurs when the firm sets up a plant or service delivery facility in a foreign location with the goal of selling in that market, and without abandoning production of the good or service in the home country. The decision to engage in horizontal expansion is driven by forces different than those for vertical expansion. Production of a good or service in a foreign market is desirable in the presence of protectionist barriers, high transportation costs, unfavorable currency exchange rate shifts, or requirements for local adaptation to the peculiarities of local demand that make exporting from the home country unfeasible or unprofitable. However, these obstacles are merely a necessary condition for horizontal expansion, but not a sufficient one. The firm should ponder the relative merits of licensing a local producer in the foreign market (or establishing an alliance) against those of committing to a foreign investment. The sufficient condition for setting up a proprietary plant or service facility has to do with the possession of intangible assets—brands, technology, know-how, and other firm-specific skills—that make licensing a risky option because the licensee might appropriate, damage or otherwise misuse the firm’s assets.10

Scholars in the field of international management have also acknowledged that firms in possession of the requisite competitive advantages do not become MNEs overnight, but in a gradual way, following different stages. According to the framework originally proposed by researchers at the University of Uppsala in Sweden,11 firms expand abroad on a country-by-country basis, starting with those more similar in terms of socio-cultural distance. They also argued that in each foreign country firms typically followed a sequence of steps: on-and-off exports, exporting through local agents, sales subsidiary, and production and marketing subsidiary. A similar set of explanations and predictions was proposed by Vernon12 in his application of the product life cycle to the location of production. According to these perspectives, the firm commits resources to foreign markets as it accumulates knowledge and experience, managing the risks of expansion and coping with the liability of foreignness. An important corollary is that the firm expands abroad only as fast as its experience and knowledge allows.

Enter the “New” Multinationals

The early students of the phenomenon of MNEs from developing, newly industrialized, emerging, or upper-middle-income countries focused their attention on both the vertical and the horizontal investments undertaken by these firms, but they were especially struck by the latter. Vertical investments, after all, are easily understood in terms of the desire to reduce uncertainty and minimize opportunism when assets are dedicated or specific to the supply or the downstream activity, whether the MNE comes from a developed country or not.13 The horizontal investments of the new MNEs, however, are harder to explain because they are supposed to be driven by the possession of intangible assets, and firms from developing countries were simply assumed not to possess them, or at least not to possess the same kinds of intangible assets as the classic MNEs from the rich countries.14 This paradox becomes more evident with the second wave of foreign direct investment (FDI) from the developing world, the one starting in the late 1980s. In contrast with the first wave FDI from developing countries that took place in the 1960s and 70s,15 the new MNEs of the 1980s and 90s aimed at becoming world leaders in their respective industries, not just marginal players.16 In addition, the new MNEs do not come only from emerging countries. Some firms labeled as born-global, born-again born-globals or born-regionals17 have emerged from developed countries following accelerated paths of internationalization that challenge the conventional view of international expansion.

The new MNEs of the 1980s and 90s aimed at becoming world leaders in their respective industries, not just marginal players. In addition, the new MNEs do not come only from emerging countries

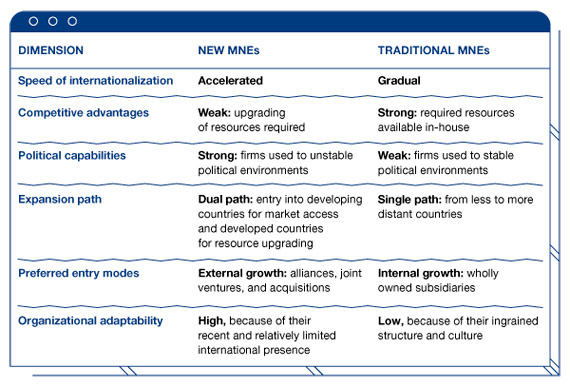

The main features of the new MNEs, as compared to the traditional ones, appear in Table 1. The dimensions in the table highlight the key differences between new and conventional MNEs. Perhaps the most startling one has to do with the accelerated pace of internationalization of the new MNEs, as firms from emerging economies have attempted to close the gap between their market reach and the global presence of the MNEs from developed countries.18 A second feature of the new MNEs is that, no matter the home country, they have been forced to deal not only with the liability of foreignness, but also with the liability and competitive disadvantage that stems from being latecomers lacking the resources and capabilities of the established MNEs from the most advanced countries. For this reason, the international expansion of the new MNEs runs in parallel with a capability upgrading process through which newcomers seek to gain access to external resources and capabilities in order to catch up with their more advanced competitors, that is, to reduce their competitiveness gap with established MNEs.19 However, despite lacking the same resource endowment of MNEs from developed countries, the new MNEs usually have an advantage over them, as they tend to possess stronger political capabilities. As the new MNEs are more used to deal with discretionary and/or unstable governments in their home country, they are better prepared than the traditional MNEs to succeed in foreign countries characterized by a weak institutional environment.20 Taking into account the high growth rates of emerging countries and their peculiar institutional environment, political capabilities have been especially valuable for the new MNEs.

Table 1. The New Multinational Enterprises Compared to Traditional Multinationals

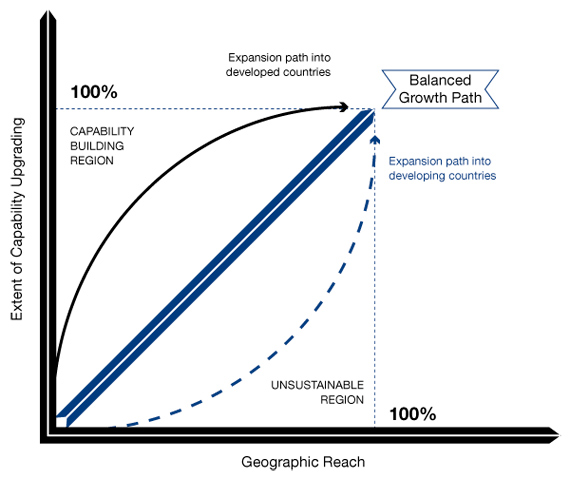

The first three features taken together point to another key characteristic of the new MNEs: they face a significant dilemma when it comes to international expansion because they need to balance the desire for global reach with the need to upgrade their capabilities. They can readily use their home-grown competitive advantages in other emerging or developing countries, but they must also enter more advanced countries in order to expose themselves to cutting-edge demand and develop their capabilities. This tension is reflected in Figure 1. Firms may evolve in a way that helps them to upgrade their capabilities or gain geographic reach, or both. Although some emerging market multinationals can focus only on emerging markets for their international expansion, becoming what Ramamurti and Singh21 call local optimizers, the corporate expansion of the new multinationals typically entails moving simultaneously in both directions: capability upgrading and geographic reach. Along the diagonal, the firm pursues a balanced growth path, with the typical expansion pattern of the established multinationals. Above the diagonal it enters the region of capability building, in which the firm sacrifices the number of countries entered (i.e., its geographic reach) so as to close the gap with other competitors, especially in the advanced economies. Below the diagonal the firm enters the unsustainable region because prioritizing global reach without improving firm competences jeopardizes the capability upgrading process. The tension between capability upgrading and gaining global reach forces the new MNEs to enter developed and developing countries simultaneously since the beginning of their international expansion. Entering developing countries helps them gain size and operational experience, and generate profits, while venturing into developed ones contributes primarily to the capability upgrading process. The new MNEs have certainly tended to expand into developing countries at the beginning of their international expansion and limit their presence in developed countries to only a few locations where they can build capabilities, either because they have a partner there or because they have acquired a local firm. As they catch up with established MNEs, they begin to invest more in developed countries in search of markets, though they also make acquisitions in developed markets in order to secure strategic assets such as technology or brands.

Figure 1. Expansion Path of New MNEs in Developed and Developing Countries

A fifth feature of the new MNEs is their preference for entry modes based on external growth (see Table 1). Global alliances22 and acquisitions23 are used by these firms to simultaneously overcome the liability of foreignness in the country of the partner/target and to gain access to their competitive advantages with the aim of upgrading their own resources and capabilities. When entering into global alliances, the new MNEs have used their home market position to facilitate the entry of their partners in exchange for reciprocal access to the partners’ home markets and/or technology. Besides the size of the domestic market, the stronger the position of new MNEs in it, the greater the bargaining power of the new MNEs to enter into these alliances. This fact is illustrated by the case of some new MNEs competing in the domestic appliances industry like China’s Haier, Mexico’s Mabe or Turkey’s Arcelik, whose international expansion was boosted by alliances with world leaders that allowed them to upgrade their technological competences.24 Capability upgrading processes have been possible in some cases due to the new MNEs’ privileged access to financial resources, because of government subsidies or capital market imperfections.25

A final feature of the new MNEs is that they enjoy more freedom to implement organizational innovations to adapt to the requirements of globalization because they do not face the constraints typical of established MNEs. As major global players with long histories, many MNEs from the developed economies suffer from inertia and path dependence due to their deeply ingrained values, culture and organizational structure. Mathews26 shows how the new MNEs from Asia have adopted a number of innovative organizational forms that suited their needs, including networked and decentralized structures.

When analyzing the foreign investments of the new MNEs of the 1960s and 70s, scholars focused their attention on two important questions, namely, their motivations and their proprietary, firm-specific advantages, if any. The following sections deal with these two issues.

Motivations of New MNEs

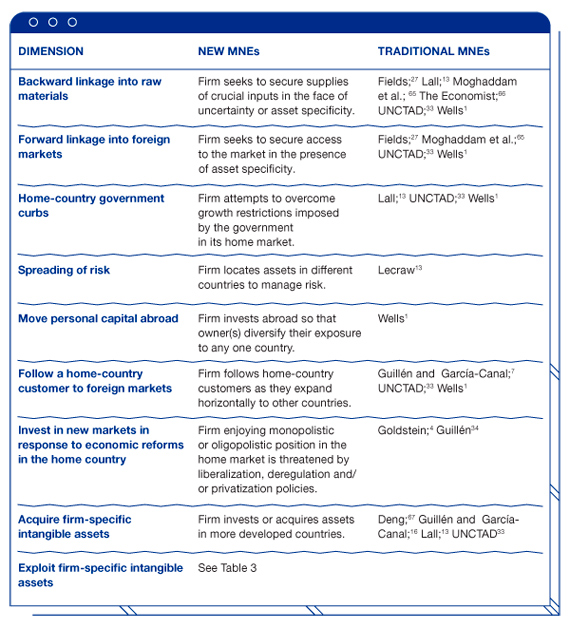

Table 2 summarizes the main motivations identified in the literature. As noted above, scholars documented and readily explained the desire of some of the new MNEs to create backward linkages into sources of raw materials or forward linkages into foreign markets in order to reduce uncertainty and opportunism in the relationship between the firm and the supplier of the raw material, or between the firm and the distributor or agent in the foreign market. Research documented, especially in the cases of South Korean and Taiwanese firms, their drive to internalize backward and forward linkages through the creation of trading companies, in some cases with government encouragement and financial support.27 For example, while during the 1960s a tiny proportion of South Korea’s exports reached foreign markets through the distribution and sale channels established by South Korean firms, by the 1980s roughly 50% of them were fully internalized, that is, handled by the exporters themselves.28 As would be expected, the new MNEs felt the pressures of uncertainty and asset specificity more strongly if they had developed intangible assets. For instance, using evidence on a representative cross-sectional sample of 837 Spanish exporting firms as of 1992, Campa and Guillén (1999)29 found that those with greater expenditures on R&D were more likely to internalize export operations. A survey performed by CNUCYD in 2006 of the empirical evidence determined that many of the new MNEs, especially in the extractive and manufacturing sectors, became multinationals when they internalized backward or forward linkages.

Table 2. Motivations for Foreign Direct Investment by the New Multinational Enterprises

Scholars also documented that developing-country MNEs wished to expand abroad in order to overcome limitations imposed by the home-country government in the domestic market. In many developing and newly industrialized countries, limitations such as licensing systems, quota allocations, and export restrictions deprived firms from having enough growth opportunities at their disposal; hence the desire to expand abroad.30 In part related to the previous motive, firms felt the need to spread risks by locating assets in different countries.31 This motivation was driven by the macroeconomic and political volatility characteristic of so many developing and newly industrialized countries. A variation on this effect has to do with the case of family-owned MNEs from developing countries under the threat of government scrutiny or confiscation.32

The early literature on the new MNEs also identified buyer-supplier relationships as motives for a supplier establishing production facilities in a foreign country in which the buyer already had a presence.33 In some cases, both the buyer and the supplier are home-country firms that followed each other abroad, while in others the buyer is a multinational from a developed country that asks its supplier in a developing or newly industrialized country to co-locate either in its home country or in other countries.34

Firm-Specific Assets

Scholars also devoted attention to the proprietary, firm-specific intangible assets of the new MNEs, noting that they engaged in foreign direct investment with the purpose of not only acquiring such assets but also exploiting existing ones. Foreign expansion with a view to acquiring intangible assets, especially technology and brands, was not very important during the 1970s and 80s, but has become widespread in the last two decades.35 With the advent of current account and currency exchange liberalization in many developing and newly industrialized countries, the new MNEs have enjoyed more of a free hand in terms of making acquisitions, including multi-billion dollar deals. Many of these have targeted troubled companies or divisions located in the United States and Europe that possess some brands and product technology that the new MNE is in a better position to exploit because of its superior or more efficient manufacturing abilities.36

The new multinationals scored lower on technology, marketing skill, organizational overhead, scale, capital intensity, and control over foreign subsidiaries than their rich-country counterparts

Acquisitions have not been the only way to gain access to intangible assets. The evidence suggests that the acceleration in the international expansion of the new MNEs has been backed by a number of international alliances aimed at gaining access to critical resources and skills that allow these firms to catch up with MNEs from developed countries. As argued above, these alliances and acquisitions have been critical for these firms to match the competitiveness of MNEs from developed countries. For this reason the international expansion of new MNEs runs in parallel with the process of upgrading their capabilities. Sometimes, however, capability upgrading precedes international expansion. This is the case, for instance, of some state-owned enterprises that undergo a restructuring process before their internationalization and privatization.37 In other cases the capability upgrading process can follow international expansion. This can happen in regulated industries, where firms face strong incentives to commit large amounts of resources and to establish operations quickly, whenever and wherever opportunities arise, and frequently via acquisition as opposed to greenfield investment.38 As opportunities for international expansion in these industries depend on privatization and deregulation, some firms lacking competitive advantages expand abroad on the basis of free cash-flows as opportunities arise. As noted above, horizontal investments seemed to pose a challenge to established theories of the MNE. The literature had emphasized since the late 1950s that MNEs in general undertake horizontal investments on the basis of intangible assets such as proprietary technology, brands, or know-how. The early literature on the new multinationals simply assumed that firms from developing or newly industrialized countries lacked the kind of intangible assets characteristic of American, Japanese or European multinationals.39 In fact, study after study found that the new multinationals scored lower on technology, marketing skill, organizational overhead, scale, capital intensity, and control over foreign subsidiaries than their rich-country counterparts.40

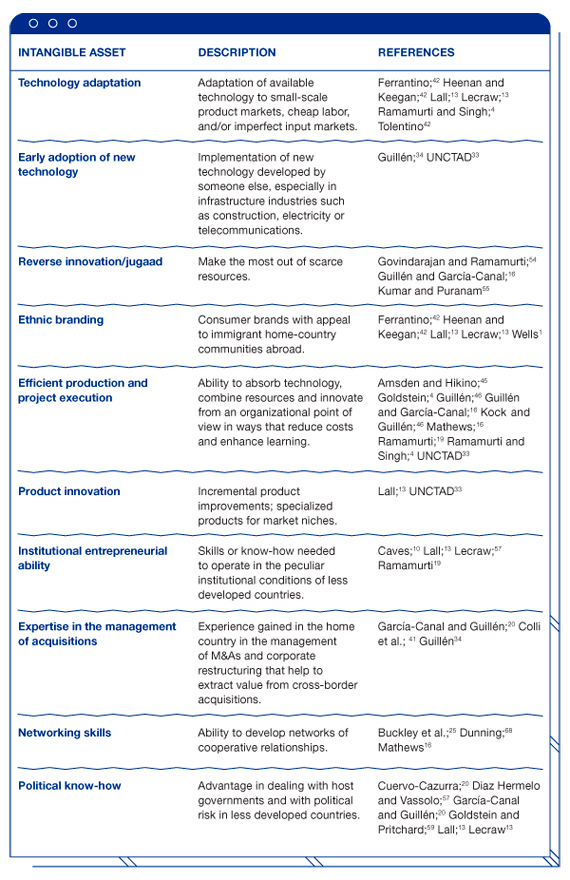

Still, horizontal investments cannot be explained without the presence of intangible assets of some sort. Even though new multinationals may lack proprietary assets, they have developed other kinds of competitive advantages that they can display in foreign markets.41 Table 3 summarizes the main types of intangible assets possessed by the new MNEs, as reflected in the existing literature. During the 1970s and 80s, the scholarly attention focused on capabilities such as the adaptation of technology to the typically smaller-scale markets of developing and newly industrialized countries, their cheaper labor, or imperfect input markets.42 Consumer-goods MNEs from these countries were also found to possess a different kind of intangible asset, namely “ethnic brands” that appealed to customers not only in the home market but also to the ethnic diaspora in foreign countries, especially in Europe and the United States.43 Other scholars noted that the new MNEs possessed an uncanny ability to incrementally improve available products and to develop specialized variations for certain market niches.44

Table 3. Intangible Assets of the New Multinational Enterprises

During the 1980s students of the so-called East Asian miracle highlighted yet another intangible asset, one having to do with the ability to organize production and to execute large-scale projects efficiently with the help of technology borrowed from abroad in industries as diverse as steel, electronics, automobiles, shipbuilding, infrastructure development, and turnkey plant construction.45 Scholars also proposed that these capabilities facilitated the growth of diversified business groups,46 which in turn made it easier for firms within the same group to expand and invest abroad by drawing on shared financial, managerial, and organizational resources.47 A specific type of managerial skill that becomes critical in accelerated internationalization is the ability to manage effectively organizational combinations such as mergers and acquisitions or strategic alliances. These abilities become critical when extracting value from these deals, deals that are necessary to learn and gain access to critical resources to increase the international competitiveness of the firm.48 The accrued skills in the management of M&As and corporate restructuring by large Spanish firms competing in regulated industries were critical for their international expansion in Latin America.49 Buckley et al.,50 analyzing the success of Chinese firms capitalizing on the Chinese diaspora, argued that some firms have the ability to engage in beneficial relationships with other firms having valuable resources needed to succeed in global markets. The adoption of network-based structures has also helped the development of the new MNEs by making easier the coordination of the international activities.51 However, home-country networks in several cases have also allowed these firms to take advantage of the experience of the firms with whom they have a tie.52

A specific type of managerial skill that becomes critical in accelerated internationalization is the ability to manage effectively organizational combinations such as mergers and acquisitions or strategic alliances

In more recent years, students of the new MNEs have drawn attention to other types of intangible assets. On the technology side, research has documented that firms in developing, newly industrialized, and upper-middle-income countries face lower hurdles when it comes to adopting new technology than their more established counterparts in rich countries. This is especially the case in industries such as construction, electricity, port operators or telecommunications, in which companies from Brazil, Chile, Mexico, South Korea, Spain, and Dubai, among other countries, have demonstrated a superior ability to borrow technology and organize efficient operations across many markets.53 Interestingly, Govindarajan and Ramamurti54 point out that new MNEs are also capable of coming up with innovative products which they later sell in developed markets in a process called “reverse innovation”.55 Another area of recent theoretical and empirical research has to do with the political know-how that the new MNEs seem to possess by virtue of having been forced to operate in heavily regulated environments at first, and then rapidly deregulating ones, as illustrated by the expansion of Spanish banking, electricity, water, and telecommunications firms throughout Latin America and, more recently, Europe.56 This “political” capability was not lost on the early students of the new MNEs; they duly pointed out that these firms possessed an “institutional entrepreneurial ability” that enabled them to operate effectively in the peculiar political, regulatory, and cultural conditions characteristic of developing countries.57 Political and regulatory risk management was identified in some early studies as a key competitive capability.58 In the last twenty years a new twist has been added to this theoretical insight after observing that the new MNEs are making acquisitions and increasing their presence in the infrastructure industries of the rich countries of Europe and North America, including electricity generation and distribution, telecommunications, water, and airport, ports and toll-highway operation, among others.59 The recent corporate expansion into Latin America of Spanish firms from regulated industries illustrates how firms tend to invest in those countries where their political capabilities are more valuable, that is, those with high political instability. Spanish firms from regulated industries reduced over time their propensity to invest in politically unstable countries, showing that it is easier to move from politically unstable countries to stable ones than the other way around.60

It is cardinal to note that while the managerial, organizational, and political skills of the new multinationals may not be “patentable,” they are rare, difficult to imitate and valuable, the three conditions identified in the resource-based view of the firm as characterizing a true “capability”.61 The international expansion of the new multinationals cannot be understood without taking into account these non-technological proprietary intangible assets, which have enabled them to obtain scarcity rents in addition to the extraordinary profits arising from imperfect competition. Thus, intangible assets have played a key role in the rise of the new multinationals, but the assets themselves tend not to be technology and brands, as in the case of traditional multinationals,62 but managerial, organizational, and political in nature.

Learning from the New Multinationals

In our recent book63 we have distilled the competitive capabilities of the emerging-market multinationals into seven principles that companies from any country in the world should adopt in order to be ready for the new kind of intense global competition of the 21st century. First, we argue that action should take precedence over strategy. In the rapidly changing global economy, companies need to experiment and to adapt incrementally rather than wait for the “perfect” strategy to arrive. We illustrate this principle with the rise to global prominence of Bimbo, whose emphasis on operations and execution rather than strategy enabled it to become the world’s leading bread company. The second principle has to do with niche thinking. Companies must follow the path of least resistance into foreign markets, which typically is a narrow niche they can dominate. Later, they can use that niche as a platform or beachhead for mounting an assault on the mainstream of the market. This is the strategy followed by Haier in the United States, a company that first targeted college students, and now is the world’s largest appliance brand in the world.

The third principle involves building up scale fast so as to pre-empt competitors, attract price-sensitive customers, and build up market share. Samsung Electronics is perhaps the company that illustrates this principle best. It bet the farm by investing in huge factories for new products not just once but several times. It is now the world’s largest consumer electronics company. If scale is important in the global economy, so is the ability to embrace chaos, the fourth principle. Acer expanded throughout the world without fearing chaos, either externally or internally. It used a network of local partners to minimize risk and maximize adaptation. Today the company is the second largest personal computer brand in the world. In order to sustain rapid growth, and to learn new capabilities along the way, we propose a fifth principle which urges companies to acquire smart, in the dual sense of buying assets that complement its existing capabilities, and doing so at the right time and with a clear integration strategy in mind. Scale through internal and external growth should enable the company to implement our sixth principle: expand with abandon. We argue that if a company waits to make a foreign move until it is ready, then it has waited too long. Foreign expansion cannot be planned day by day. Companies need to be willing to experiment, to engage in trial-and-error, to expose themselves to new opportunities and ways of doing things.

And it is at this point where our seventh, and most important, recommendation comes in. In this new, rapidly-changing global economy companies must abandon the sacred cows. What brought them success in the past cannot become a hindrance for pursuing the new opportunities that are becoming available around the world.

Conclusion

The new MNEs are the result of both imitation of established MNEs from the rich countries—which they have tried to emulate strategically and organizationally—and innovation in response to the peculiar characteristics of emerging and developing countries. The context in which their international expansion has taken place is also relevant. The new MNEs have emerged from countries with weak institutional environments and they are used to operating in countries with weak property-rights regimes, legal systems, and so on. Experience in the home country became especially valuable for the new MNEs because many countries with weak institutions are growing fast and they had developed the capabilities to compete in such challenging environments.

The meager international presence of the new MNEs allowed them to adopt a strategy and organizational structure most appropriate to the current international environment

In addition, the new MNEs have flourished at a time of market globalization in which, despite the local differences that still remain, global reach and global scale are crucial. The new MNEs have responded to this challenge by embarking on an accelerated international strategy based on external growth aimed at upgrading their capabilities and increasing their global market reach. When implementing this strategy, the new MNEs took advantage of their market position in the home country and, ironically, their meager international presence allowed them to adopt a strategy and organizational structure that happens to be most appropriate to the current international environment in which emerging economies are growing very fast.

It is also important to note that the established MNEs from the rich countries have adopted some of the patterns of behavior of the new multinationals. Increased competitive pressure from the latter in industries such as cement, steel, electrical appliances, construction, banking, and infrastructure has prompted many American and European firms to become much less reliant on traditional product-differentiation strategies and vertically integrated structures. To a certain extent, the rise of networked organizations64 and the extensive shift towards outsourcing represent competitive responses to the challenges faced by established MNEs. Finally, a special type of new MNE is the so-called born-global firm, which resembles the new MNE in many ways but has emerged from developed countries.

Taking all of these developments into account, it is clear that the traditional model of MNE is fading. In effect, globalization, technical change, and the coming of age of the emerging countries have facilitated the rise of a new type of MNE in which foreign direct investment is driven not only by the exploitation of firm-specific competences but also by the exploration of new patterns of innovation and ways of accessing markets. In addition, the new MNEs have expanded very rapidly, without following the gradual, staged model of internationalization.

It is important to note, however, that the decline of the traditional model of the MNE does not necessarily imply the demise of existing theories of the MNE. In fact, the core explanation for the existence of MNEs remains, namely, that in order to pursue international expansion, the firm needs to possess capabilities allowing it to overcome the liability of foreignness; no firm-specific capabilities, no multinationals. Our analysis of the new MNEs has shown that their international expansion was possible due to some valuable capabilities developed in the home country, including project-execution, political, and networking skills, among other non-conventional ones. Thus, the lack of the classic technological or marketing capabilities does not imply the absence of other valuable capabilities that may provide the foundations for international expansion. It is precisely for this reason that the new MNEs are here to stay.

Notes

- L.T. Wells Jr., Third World Multinationals: The Rise of Foreign Investment from Developing Countries (Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 1983).

- J.A. Mathews, Dragon Multinationals: A New Model of Global Growth (New York: Oxford University Press, 2002).

- P.P. Li, “Toward a Geocentric Theory of Multinational Evolution: The Implications from the Asian MNEs as Latecomers,” Asia Pacific Journal of Management 22.2 (June 2003), 217-42.

- Accenture, “The Rise of the Emerging-Market Multinational”, 2008; A. Goldstein, Multinational Companies from Emerging Economies (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2007); R. Ramamurti and J.V. Singh (eds.), Emerging Multinationals in Emerging Markets (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2009).

- Mathews, Dragon Multinationals, 2002.

- Cuervo-Cazurra, “The Multinationalization of Developing Country MNEs: The Case of Multilatinas,” Journal of International Management, 14.2 (June 2008), 138-54.

- M.F. Guillén and E. García-Canal, The New Multinationals: Spanish Firms in a Global Context (Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press, 2010).

- CNUCYD (United Nations Conference on Trade and Development), “World Investment Report 2008” (New York & Geneva: United Nations, 2008).

- S. Hymer, “The International Operations of National Firms: A Study of Direct Foreign Investment,” PhD thesis (MIT, 1960), p.25 (publ. Cambridge: The MIT Press, 1976).

- For a summary of the basic economic model of the multinational firm, see R.E. Caves, Multinational Enterprise and Economic Analysis (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1996). Stephen Hymer [1960] was the first to observe that firms expand horizontally to protect (and monopolize) their intangible assets. Other important contributions are: P.J. Buckley and M. Casson, The Future of the Multinational Enterprise (London: Macmillan, 1976); J.F. Hennart, A Theory of Multinational Enterprise (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1982); and D.J. Teece, “Technology Transfer by Multinational Firms: The Resource Cost of Transferring Technological Know-How,” Economic Journal, 87.346 (1977), 242-61.

- J. Johanson and J.-E. Vahlne, “The Internationalization Process of the Firm: A Model of Knowledge Development and Increasing Foreign Market Commitments,” Journal of International Business Studies, 8.1 (1977), 23-32; J. Johanson and F. Wiedersheim-Paul, “The Internationalization of the Firm—Four Swedish Cases,” Journal of Management Studies, 12 (October 1975), 305-22.

- R. Vernon, “International Investment and International Trade in the Product Cycle,” Quarterly Journal of Economics, 80 (1966), 190-207; “The Product Cycle Hypothesis in a New International Environment,” Oxford Bulletin of Economics and Statistics, 41.4 (November 1979), 255-67.

- Caves, Multinational Enterprise, 1996, pp.238-241; S. Lall, The New Multinationals (New York: Wiley, 1983); D. Lecraw, “Direct Investment by Firms from Less Developed Countries,” Oxford Economic Papers, 29 (November 1977), 445-57; Wells, Third World Multinationals, 1983.

- Lall, New Multinationals, 1983, p.4.

- Lall, New Multinationals, 1983; Wells, Third World Multinationals, 1983.

- Guillén and García-Canal, New Multinationals, 2010; M.F. Guillén and E. García-Canal, Emerging Markets Rule (New York: McGraw-Hill, 2013); J.A. Mathews, “Dragon Multinationals,” Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 23 (2006), 5-27.

- C.G. Asmussen, “Local, Regional, or Global? Quantifying MNE Geographic Scope,” Journal of International Business Studies, 40 (2009), 1192-1250; J. Bell, R. McNaughton, and S. Young, “Born-again Global Firms: An Extension to the Born Global Phenomenon,” Journal of International Management, 7.3 (2001), 173-90; N. Hashai, “Sequencing the Expansion of Geographic Scope and Foreign Operations by Born Global Firms,” Journal of International Business Studies, 42 (2011), 995-1015; S. Khavul, L. Pérez-Nordtvedt, and E. Wood, “Organizational Entrainment and International New Ventures from Emerging Markets,” Journal of Business Venturing, 25 (2010), 104-19; T.K. Madsen, “Early and Rapidly Internationalizing Ventures: Similarities and Differences Between Classifications Based on The Original International New Venture and Born Global Literatures,” Journal of International Entrepreneurship, 11.1 (2013), 65-79; A. Rialp, J. Rialp, and G.A. Knight, “The Phenomenon of Early Internationalizing Firms: What Do We Know After a Decade (1993-2003) of Scientific Enquiry?” International Business Review, 14.2 (April 2005), 147-66; L. Zhou, W. Wu, and X. Luo, “Internationalization and the Performance of Born-Global SMEs: The Mediating Role of Social Networks,” Journal of International Business Studies, 38 (2007), 673-90.

- P.J. Buckley and N. Hashai, “The Role of Technological Catch Up and Domestic Market Growth in the Genesis of Emerging Country Based Multinationals,” Research Policy, 43.2 (2014), 423-37; Mathews, “Dragon Multinationals,” 2006.

- P.S. Aulakh, “Emerging Multinationals from Developing Countries: Motivations, Paths and Performance,” Journal of International Management, 13.3 (2007), 235-40; L.A. Dau, “Learning Across Geographic Space: Pro-market Reforms, Multinationalization Strategy, and Profitability,” Journal of International Business Studies, 44 (2013), 235-62; J.F. Hennart, “Emerging Market Multinationals and the Theory of the Multinational Enterprise,” Global Strategy Journal, 2 (2012), 168-87; D. Lessard and R. Lucea, “Mexican Multinationals: Insights from CEMEX,” in Emerging Multinationals, ed. by Ramamurti and Singh, 2009; P.P. Li, “Toward an Integrated Theory of Multinational Evolution: The Evidence of Chinese Multinational Enterprises as Latecomers,” Journal of International Management, 13.3 (2007), 296-318; Mathews, “Dragon Multinationals,” 2006; R. Ramamurti, “What Have We Learned About Emerging Market MNEs?” in Emerging Multinationals, ed. by Ramamurti and Singh, 2009, 339-426; A. Verbeke and L. Kano, “An Internalization Theory Rationale for MNE Regional,” Multinational Business Review, 20.2 (2012), 135-52.

- Cuervo-Cazurra, “Extending Theory by Analyzing Developing Country Multinational Companies: Solving the Goldilocks Debate,” Global Strategy Journal, 2 (2012), 153-167; A. Cuervo-Cazurra and M. Genc, “Transforming Disadvantages into Advantages: Developing-Country MNEs in the Least Developed Countries,” Journal of International Business Studies, 39 (2008), 957-79; F. Diaz Hermelo and R. Vassolo, “Institutional Development and Hypercompetition in Emerging Economies,” Strategic Management Journal, 31 (2010), 1457-73; E. García-Canal and M.F. Guillén, “Risk and the Strategy of Foreign Location Choice,” Strategic Management Journal, 29.10 (2008), 1097-115.

- Ramamurti and Singh (eds.), Emerging Multinationals, 2009.

- E. García-Canal, C. López Duarte, J. Rialp Criado, and A. Valdés Llaneza, “Accelerating International Expansion through Global Alliances: A Typology of Cooperative Strategies,” Journal of World Business, 37.2 (2002), 91-107; J. Johanson and J.-E. Vahlne, “The Uppsala Internationalization Process Model Revisited: From Liability of Foreignness to Liability of Outsidership,” Journal of International Business Studies, 40 (2009), 1411-31.

- P.J. Buckley, S. Elia, and M. Kafouros, “Acquisitions by Emerging Market Multinationals: Implications for Firm Performance,” Journal of World Business, 49 (2014), 611-632; H. Rui and G.S. Yip, “Foreign Acquisitions by Chinese Firms: A Strategic Intent Perspective,” Journal of World Business, 43 (2008), 213-26.

- F. Bonaglia, A. Goldstein, and J.A. Mathews, “Accelerated Internationalization by Emerging Market Multinationals: The Case of the White Goods Sector,” Journal of World Business, 42 (2007), 369-83.

- P.J. Buckley, L.J. Clegg, A.R. Cross, X. Liu, H. Voss, and P. Zheng, “The Determinants of Chinese Outward Foreign Direct Investment,” Journal of International Business Studies, 38 (2007), 499-518; Buckley et al., “Acquisitions by Emerging Market Multinationals,” 2014; J. Lu, X. Liu, M. Wright, and I. Filatotchev, “International Experience and FDI Location Choices of Chinese Firms: The Moderating Effects of Home Country Government Support and Host Country Institutions,” Journal of International Business Studies, 45 (2014), 428-49.

- Mathews, “Dragon Multinationals,” 2006.

- K.J. Fields, Enterprise and the State in Korea and Taiwan (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1995), 183-237.

- D.S. Cho, The General Trading Company: Concept and Strategy (Lexington, MA: Lexington Books, 1987).

- J.M. Campa and M.F. Guillén, “The Internationalization of Exports: Firm and Location-Specific Factors in a Middle-Income Country,” Management Science, 45.11 (November 1999), 1463-78.

- Lall, New Multinationals, 1983; Wells, Third World Multinationals, 1983.

- Lecraw, “Direct Investment,” 1977.

- Wells, Third World Multinationals, 1983.

- CNUCYD (United Nations Conference on Trade and Development), “World Investment Report 2006” (New York & Geneva: United Nations, 2006); Wells, Third World Multinationals, 1983.

- M.F. Guillén, The Rise of Spanish Multinationals: European Business in the Global Economy (Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press, 2005).

- CNUCYD, “World Investment Report 2006.”

- In “Down with MNE-centric Theories! Market Entry and Expansion as the Bundling of MNE and Local Assets,” Journal of International Business Studies, 40.9 (2009), 1432-54,

- J.F. Hennart argues that the greater efficiency in markets for assets and asset services in developed countries makes firms less diversified and, for this reason, more modular, i.e., easier to be taken over and integrated by an emerging market multinational willing to acquire external technology and know-how.

- Cuervo and B. Villalonga, “Explaining the Variance in the Performance Effects of Privatization,” Academy of Management Review, 25 (2000), 581-90.

- Buckley et al., “Acquisitions by Emerging Market Multinationals,” 2014; García-Canal and Guillén, “Risk and the Strategy of Foreign Location Choice,” 2008; Guillén and García-Canal, Emerging Markets Rule, 2013; M.W. Peng, “The Global Strategy of Emerging Multinationals from China,” Global Strategy Journal, 2 (2012), 97-107; M.B. Sarkar, S.T. Cavusgil, and P.S. Aulakh, “International Expansion of Telecommunication Carriers: The Influence of Market Structure, Network Characteristics and Entry Imperfections,” Journal of International Business Studies, 30 (1999), 361-82.

- Lall, New Multinationals, 1983, 4.

- Lall, New Multinationals, 1983; Lecraw, “Direct Investment,” 1977; Wells, Third World Multinationals, 1983.

- A. Colli, E. García-Canal, and M.F. Guillén, “Family Character and International Entrepreneurship: A Historical Comparison of Italian and Spanish New Multinationals,” Business History, 55.1 (2013), 119-38; A. Madhok and M. Keyhani, “Acquisitions as Entrepreneurship: Asymmetries, Opportunities, and the Internationalization of Multinationals from Emerging Economies,” Global Strategy Journal, 2 (2012), 26-40; Ramamurti and Singh (eds.), Emerging Multinationals, 2009.

- M.J. Ferrantino, “Technology Expenditures, Factor Intensity, and Efficiency in Indian Manufacturing,” Review of Economics and Statistics, 74.4 (1992), 689-700; D.A. Heenan and W.J. Keegan, “The Rise of Third World Multinationals,” Harvard Business Review, 57 (January-February 1979), 101-9; Lall, New Multinationals, 1983; Lecraw, “Direct Investment,” 1977; Ramamurti and Singh (eds.), Emerging Multinationals, 2009; P.E. Tolentino, Technological Innovation and Third World Multinationals (London: Routledge, 1993).

- Ferrantino, “Technology Expenditures,” 1992; Goldstein, Multinational Companies, 2007, 117-122; Lecraw, “Direct Investment,” 1977; Wells, Third World Multinationals, 1983.

- Lall, New Multinationals, 1983; CNUCYD, “World Investment Report 2006.”

- A.H. Amsden and T. Hikino, “Project Execution Capability, Organizational Know-How and Conglomerate Corporate Growth in Late Industrialization,” Industrial & Corporate Change, 3.1 (1994), 111-47.

- M.F. Guillén, “Business Groups in Emerging Economies: A Resource-Based View,” Academy of Management Journal, 43.3 (June 2000), 362-80; Guillén and García-Canal, Emerging Markets Rule, 2013; C. Kock and M.F. Guillén, “Strategy and Structure in Developing Countries: Business Groups as an Evolutionary Response to Opportunities for Unrelated Diversification,” Industrial & Corporate Change, 10.1 (2001), 1-37; Ramamurti, “What Have We Learned About Emerging Market MNEs?” 2009; Ramamurti and Singh (eds.), Emerging Multinationals, 2009.

- Goldstein, Multinational Companies, 2007; M.F. Guillén, “Structural Inertia, Imitation, and Foreign Expansion: South Korean Firms and Business Groups in China, 1987-1995,” Academy of Management Journal, 45.3 (June 2002), 509-25; Lall, New Multinationals, 1983, p.6; Mathews, “Dragon Multinationals,” 2006; CNUCYD, “World Investment Report 2006.”

- Guillén and García-Canal, Emerging Markets Rule, 2013; S. Henningsson and S. Carlsson, “The DySIIM Model for Managing IS Integration in Mergers and Acquisition,” Information Systems Journal, 21 (2011), 441-476; P. Kale, H. Singh, and H.V. Perlmutter, “Learning and Protection of Proprietary Assets in Strategic Alliances: Building Relational Capital,” Strategic Management Journal, 21 (2000), 217-37; M. Ruess and S.C. Voelpel, “The PMI Scorecard: A Tool For Successfully Balancing the Post-Merger Integration Process,” Organizational Dynamics, 41 (2012), 78-84; M. Zollo and H. Singh, “Deliberate Learning in Corporate Acquisitions: Post-Acquisition Strategies and Integration Capability in US Bank Mergers,” Strategic Management Journal, 25 (2004), 1233-56.

- García-Canal and Guillén, “Risk and the Strategy of Foreign Location Choice,” 2008; Guillén, The Rise of Spanish Multinationals, 2005.

- Buckley et al., “The Determinants of Chinese Outward Foreign Direct Investment,” 2007.

- Mathews, “Dragon Multinationals,” 2006.

- B. Elango and C. Pattnaik, “Building Capabilities for International Operations through Networks: A Study of Indian Firms,” Journal of International Business Studies, 38 (2007), 541-55; D.W. Yiu, C.M. Lau, and G.D. Bruton, “International Venturing by Emerging Economy Firms: The Effects of Firm Capabilities, Home Country Networks, and Corporate Entrepreneurship,” Journal of International Business Studies, 38 (2007), 519-40.

- Guillén, The Rise of Spanish Multinationals, 2005; CNUCYD, “World Investment Report 2006.”

- V. Govindarajan and R. Ramamurti, “Reverse Innovation, Emerging Markets, and Global Strategy,” Global Strategy Journal, 1 (2011), 191-205.

- N. Kumar and P. Puranam, India Inside: The Emerging Innovation Challenge to the West (Cambridge, MA: Harvard Business Press, 2012).

- García-Canal and Guillén, “Risk and the Strategy of Foreign Location Choice,” 2008.

- Caves, Multinational Enterprise, 1996; Cuervo-Cazurra, “Extending Theory,” 2012; Diaz Hermelo and Vassolo, “Institutional Development,” 2010; Goldstein, Multinational Companies, 2007, pp.99-102; Lall, New Multinationals, 1983; D. Lecraw, “Outward Direct Investment by Indonesian Firms: Motivation and Effects,” Journal of International Business Studies, 24.3 (1993), 589-600; Ramamurti, “What Have We Learned About Emerging Market MNEs?” 2009.

- Lall, New Multinationals, 1983; Lecraw, “Direct Investment,” 1977.

- Guillén, The Rise of Spanish Multinationals, 2005; see also A. Goldstein and W. Pritchard, “South African Multinationals: Building on a Unique Legacy,” in Emerging Multinationals, ed. by Ramamurti and Singh, 2009.

- García-Canal and Guillén, “Risk and the Strategy of Foreign Location Choice,” 2008.

- J. Barney, “Strategic Factor Markets: Expectations, Luck, and Business Strategy,” Management Science, 32.10 (1986), 1231-41; C.C. Markides and P.J. Williamson, “Corporate Diversification and Organizational Structure: A Resource-Based View,” Academy of Management Journal, 39.2 (April 1996), 340-67; M.A. Peteraf, “The Cornerstones of Competitive Advantage: A Resource-Based View,” Strategic Management Journal, 14.3 (March 1993), 179-91.

- Caves, Multinational Enterprise, 1996.

- Guillén and García-Canal, Emerging Markets Rule, 2013.

- C.A. Bartlett and S. Ghoshal, Managing Across Borders: The Transnational Solution (Boston: Harvard Business School Press, 1989).

- K. Moghaddam, D. Sethi, T. Weber, and J. Wu, “The Smirk of Emerging Market Firms: A Modification of the Dunning’s Typology of Internationalization Motivations,” Journal of International Management, 20 (2014), 359–74.

- “China Buys Up the World,” The Economist, November 11, 2010.

- P. Deng, “Why do Chinese Firms Tend to Acquire Strategic Assets in International Expansion?” Journal of World Business, 44.1 (2009), 74-84.

- J.H.Dunning, “Relational Assets, Networks and International Business Activity,” in Cooperative Strategies and Alliances, ed. by F.J. Contractor and P.E. Lorange (Amsterdam and Boston: Pergamon Press, 2002), 569-94.

Comments on this publication