The First Age: The Creation of Shared Beliefs

Seven million years ago, the first ancestors of mankind appeared in Africa and seven million years later, as we speak, mankind’s existence is being traced by archaeologists in South Africa, where they believe they are finding several missing links in our history. A history traced back to the first hominid forms. What is a hominid, I hear you say, and when did it exist?

Synthetic polymer paint and silkscreen ink on canvas, 35.56 x 27.94 cm, The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc., New York, USA.

Well, way back when scientists believe that the Eurasian and American tectonic plates collided and then settled, creating a massive flat area in Africa, after the Ice Age. This new massive field was flat for hundreds of miles, as far as the eye could see, and the apes that inhabited this land suddenly found there were no trees to climb. Instead, just flat land, and berries, and grasses. This meant that the apes found it hard going thundering over hundreds of miles on their hands and feet, so they started to stand up to make it easier to move over the land. This resulted in a change in the wiring of the brain, which, over thousands of years, led to the early forms of what is now recognized as human.

The first link to understanding this chain was the discovery of Lucy. Lucy—named after the Beatles song “Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds”—is the first skeleton that could be pieced together to show how these early human forms appeared on the African plains in the post-Ice Age world. The skeleton was found in the early 1970s in Ethiopia by paleoanthropologist Donald Johanson and is an early example of the hominid australopithecine, dating back to about 3.2 million years ago. The skeleton presents a small skull akin to that of most apes, plus evidence of a walking gait that was bipedal and upright, similar to that of humans and other hominids. This combination supports the view of human evolution that bipedalism preceded an increase in brain size.

Since Lucy was found, there have been many other astonishing discoveries in what is now called the “Cradle of Humankind” in South Africa, a Unesco World Heritage site. It gained this status after the discovery of a near-complete Australopithecus skeleton called Little Foot, dating to around 3.3 million years ago, by Ron Clarke in 1997. Why was Little Foot so important? Because it is almost unheard of to find fossilized hominin remains intact. The reason is that the bones are scattered across the Earth as soil sank into the ground and remains were distributed among the porous caves underneath. An intact skeleton is therefore as likely to be found as a decent record by Jedward.

More recently, archaeologists have discovered the Rising Star Cave system, where many complete bodies have been found, and scientists believe this was a burial ground. It has also led to the naming of a new form of human relative, called Homo naledi.

All in all, the human tree of life that falls into the catchall of the Homo species, of which we are Homo sapiens, has several other tributaries including Homo erectus, Homo floresiensis, Homo habilis, Homo heidelbergensis, Homo naledi, and Homo neanderthalensis.

The question then arises: if there were several forms of human, how come we are the only ones left?

Some of that may have been due to changing times. After all, there are no Mammoths or Sabre-Toothed Tigers around today, but there are several forms of their ancestors still on Earth. Yet what is interesting in the order of Hominids, according to Professor Yuval Harari, author of Sapiens and leading authority on the history of humankind, is that Homo sapiens defeated all other forms of hominid because we could work together in groups of thousands. According to his theory, all other human forms peaked in tribes of a maximum of 150 members—about the maximum size of any ape colony—because at this size of a group, too many alpha males exist and the order of the group would fall apart. One part of the group would then follow one alpha male and another part the other. Consequently, the tribe divides and goes its separate ways.

Homo sapiens developed beyond this because we could talk to each other. We could create a rich landscape of information, not just grunts and signs, and began to build stories. By building stories, we could share beliefs and, by sharing beliefs, hundreds of us could work together in tribes, not just one hundred.

The result is that when Homo sapiens villages were attacked by other Homo forms, we could repel them easily. We could also, in return, attack those human forms and annihilate them. And we did. Neanderthals, who share about 99.5 percent of our DNA, died out 40,000 years ago and were the last Homo variation to survive. After that, it was just us human beings, or Homo sapiens if you prefer. Now why is this important as a background to the five ages of man?Because this was the first age. This was the age of enlightenment. It was the age of Gods. It was an age of worshiping the Moon and the Sun, the Earth and the Seas, Fire and Wind. The natural resources of Earth were seen as important symbols with the birds of the sky, the big cats of the Earth, and the snakes of the Earth below seen as key symbols for early humankind.We shared these stories and beliefs and, by doing so, could work together and build civilizations. One of the oldest surviving religions of the world is Hinduism, around three thousand years old, but there were other religions before Hinduism in Jericho, Mesopotamia, and Egypt. The Sun God and the Moon God were fundamental shared beliefs, and these shared beliefs were important because they maintained order. We could work together in larger and larger groups thanks to these shared beliefs.This is why a lot of Old Testament stories in the Bible have much in common with those of the Koran. Jews, Christians, and Muslims all share beliefs in the stories of Adam and Eve, Moses, Sodom and Gomorrah, and Noah, and some of these beliefs even originate from the ancient Hindu beliefs of the world.

Shared beliefs is the core thing that brings humans together and binds them. It is what allows us to work together and get on with each other, or not, as the case may be. The fundamental difference in our shared beliefs, for example, is what drives Daesh today and creates the fundamentalism of Islam, something that many Muslims do not believe in at all.

I will return to this theme since the creation of banking and money is all about a shared belief that these things are important and have value. Without that shared belief, banking, money, governments, and religions would have no power. They would be meaningless.

The Second Age of Man: the Invention of Money

So man became civilized and dominant by being able to work in groups of hundreds. This was unique to Homo sapiens form of communication, as it allowed us to create shared beliefs in the Sun, Moon, Earth, and, over time, Gods, Saints, and Priests.

Eventually, as shared beliefs united us, they joined us together in having leaders. This is a key differential between humans and monkeys. For example, the anthropologist Desmond Morris was asked whether apes believe in God, and he emphatically responded no. Morris, an atheist, wrote a seminal book in the 1960s called The Naked Ape, where he states that humans, unlike apes, “believe in an afterlife because part of the reward obtained from our creative works is the feeling that, through them, we will ‘live on’ after we are dead.”

This is part of our shared belief structure that enables us to work together, live together, and bond together in our hundreds and thousands. Hence, religion became a key part of mankind’s essence of order and structure, and our leaders were those closest to our beliefs: the priests in the temples. As man settled into communities and began to have an organized structure however, it led to new issues. Historically, man had been nomadic, searching the land for food and moving from place to place across the seasons to eat and forage. Where we were deficient in our stores of food, or where other communities had better things, we created a barter system to exchange values with each other.

You have pineapples, I have maize; let’s swap.

You have bright colored beads, I have strong stone and flint; let’s trade.

The barter trade worked well, and allowed different communities to prosper and survive.

Eventually, we saw large cities form. Some claim the oldest surviving city in the world is Jericho, dating back over 10,000 years. Others would point to Eridu, a city formed in ancient Mesopotamia—near Basra in Iraq—7,500 years ago. Either way, both cities are extremely old.

As these cities formed, thousands of people gathered and settled in them because they could support complex, civilized life.

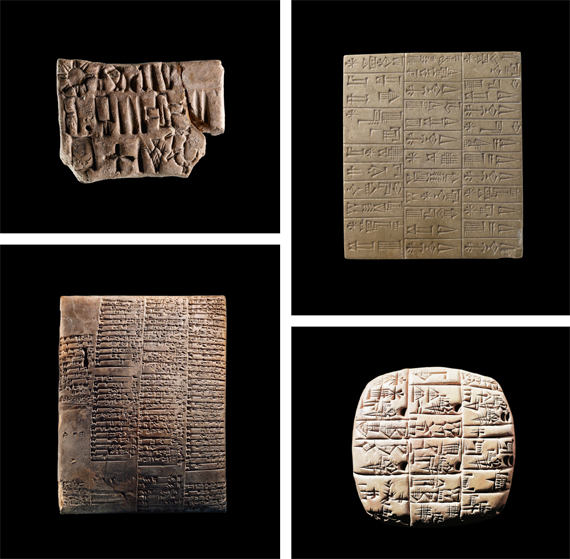

Using Eridu as the focal point, the city was formed because it drew together three ancient civilizations: the Samarra culture from the north; the Sumerian culture, which formed the oldest civilization in the world; and the Semitic culture, which had historically been nomadic with herds of sheep and goats; and it was the Sumerians who invented money.

Money: a new shared belief structure that was created by the religious leaders to maintain control.

In Ancient Sumer, the Sumerians invented money because the barter system broke down. It broke down because of humankind settling into larger groups and farming. The farming and settlement structures introduced a revolution in how humankind operated. Before, people foraged and hunted; now they settled, and farmed together.

Farming resulted in abundance and abundance resulted in the trading system breaking down. Barter does not work when everyone has pineapples and maize. You cannot trade something that someone already has. So there was a need for a new system and the leaders of the time—the government if you prefer—invented it. They invented money. Money is the control mechanism of societies and economies. Countries that have money have respected economies; countries that do not, do not.

How can America and Britain have trillions of dollars of debt, but still be Triple-A rated? Because they have good money flows linked to their economies as global financial centers, binding our shared belief structures together.

As Professor Yuval Noah Harari puts it:

The truly unique trait of [Homo] Sapiens is our ability to create and believe fiction. All other animals use their communication system to describe reality. We use our communication system to create new realities. Of course not all fictions are shared by all humans, but at least one has become universal in our world, and this is money. Dollar bills have absolutely no value except in our collective imagination, but everybody believes in the dollar bill.

So how did the priests invent this shared belief and make it viable?

Sex.

There were two Gods in Ancient Sumer: Baal, the god of war and the elements, and Ishtar,

the goddess of fertility. Ishtar made the land and crops fertile, as well as providing pleasure and love:

Praise Ishtar, the most awesome of the Goddesses,

Revere the queen of women, the greatest of the deities.

She is clothed with pleasure and love.

She is laden with vitality, charm, and voluptuousness.

In lips she is sweet; life is in her mouth.

At her appearance rejoicing becomes full.

This was the key to the Sumerian culture: creating money so that the men could enjoy pleasure with Ishtar. Men would come to the temple and offer their abundant crops to the priests. The priests would place the crops in store for harder times—an insurance against winter when food is short and against crop failure in seasons of blight and drought. In return for their abundance of goods, the priests would give the famers money. A shared belief in a new form of value: a coin.

What could you do with this coin?

Have sex of course. The Greek historian Herodotus wrote about how this worked:

Every woman of the land once in her life [is compelled] to sit in the temple of love and have intercourse with some stranger […] the men pass and make their choice. […] It matters not what be the sum of the money; the woman will never refuse, for that were a sin, the money being by this act made sacred. […] After their intercourse she has made herself holy in the goddess’s sight and goes away to her home; and thereafter there is no bribe however great that will get her. So then the women that are fair and tall are soon free to depart, but the uncomely have long to wait because they cannot fulfill the law; for some of them remain for three years, or four.

So money was sacred and every woman had to accept that she would prostitute herself for money at least once in her life. This is why Ishtar was also known by other names such as Har and Hora, from which the words harlot and whore originate.

It is why prostitution is the oldest profession in the world and accountancy the second oldest. Money was created to support religion and governments by developing a new shared belief structure that allowed society to overproduce goods and crops, and still get on with each other after barter broke down.

The Third Age: the Industrial Revolution

The use of money as a means of value exchange, alongside barter, lasted for hundreds of years or, to be more exact, about 4,700 years. During this time, beads, tokens, silver, gold, and other commodities were used as money, as well as melted iron and other materials. Perhaps the strangest money is that of the Yap Islands in the Pacific that use stone as money.

This last example is a favorite illustration of how value exchange works for bitcoin libertarians, who use the stone ledger exchange systems of the Yap Islands to illustrate how you can then translate this to digital exchange on the blockchain, as it is just a ledger of debits and credits.

The trouble is that stone, gold, and silver is pretty heavy as a medium of exchange. Hence, as the Industrial Revolution powered full steam ahead, a new form of value exchange was needed.

In this context, I use the term “full steam ahead” as a key metaphor, as the timing of the Industrial Revolution is pretty much aligned with steam power. Steam power was first patented in 1606, when Jerónimo de Ayanz y Beaumont received a patent for a device that could pump water out of mines. The last steam patent dates to 1933, when George and William Besler patented a steam-powered airplane.

The steam age created lots of new innovations, but the one that transformed the world was the invention of the steam engine. This led to railways and transport from coast to coast and continent to continent. Moving from horse power to steam power allowed ships to steam across oceans and trains across countries. It led to factories that could be heated and powered, and to a whole range of transformational moments culminating in the end of the nineteenth-century innovations of electricity and telecommunications. The move from steam to electricity moved us away from heavy-duty machinery to far lighter and easier communication and power structures. Hence, the Industrial Revolution ended when we moved from factories to offices but, between 1606 and 1933, there were massive changes afoot in the world of commerce and trade.

Within this movement of trade, it was realized that a better form of value exchange was needed, as carrying large vaults of gold bullion around was not only heavy but easily open to attack and theft. Something new was needed. There had already been several innovations in the world—the Medici bankers created trade finance and the Chinese had already been using paper money since the ninth century—but these innovations did not go mainstream until the Industrial Revolution demanded it. And this Revolution did demand a new form of value exchange.

Hence, the governments of the world started to mandate and license banks to enable economic exchange. These banks appeared from the 1600s, and were organized as government-backed entities that could be trusted to store value on behalf of depositors. It is for this reason that banks are the oldest registered companies in most economies. The oldest surviving British financial institution is Hoares Bank, created by Richard Hoare in 1672. The oldest British bank of size is Barclays Bank, first listed in 1690. Most UK banks are over two hundred years old, which is unusual as, according to a survey by the Bank of Korea, there are only 5,586 companies older than two hundred years with most of them in Japan.

Banks and insurance companies have survived so long as large entities—it is notable that they are large and still around after two to three hundred years—because they are government instruments of trade. They are backed and licensed by governments to act as financial oil in the economy, and the major innovation that took place was the creation of paper money, backed by government, as the means of exchange.

Paper bank notes and paper checks were created as part of this new ecosystem, to make it easier to allow industry to operate. At the time, this idea must have seemed most surprising. A piece of paper instead of gold as payment? But it was not so outrageous.

Perhaps this excerpt from the Committee of Scottish Bankers provides a useful insight as to why this idea took root:

The first Scottish bank to issue banknotes was Bank of Scotland. When the bank was founded on 17th July 1695, through an Act of the Scottish Parliament, Scots coinage was in short supply and of uncertain value compared with the English, Dutch, Flemish or French coin, which were preferred by the majority of Scots. The growth of trade was severely hampered by this lack of an adequate currency and the merchants of the day, seeking a more convenient way of settling accounts, were among the strongest supporters of an alternative.

Bank of Scotland was granted a monopoly over banking within Scotland for twenty-one years. Immediately after opening in 1695 the Bank expanded on the coinage system by introducing paper currency.

This idea was first viewed with some suspicion. However, once it became apparent that the Bank could honor its “promise to pay,” and that paper was more convenient than coin, acceptance spread rapidly and the circulation of notes increased. As this spread from the merchants to the rest of the population, Scotland became one of the first countries to use a paper currency from choice.

And the check book? The UK’s Cheque & Credit Clearing Company provides a useful history:

By the seventeenth century, bills of exchange were being used for domestic payments as well as international trades. Cheques, a type of bill of exchange, then began to evolve. They were initially known as ‘drawn notes’ as they enabled a customer to draw on the funds they held on account with their banker and required immediate payment […] the Bank of England pioneered the use of printed forms, the first of which were produced in 1717 at Grocers’ Hall, London. The customer had to attend the Bank of England in person and obtain a numbered form from the cashier. Once completed, the form had to be authorized by the cashier before being taken to a teller for payment. These forms were printed on ‘cheque’ paper to prevent fraud. Only customers with a credit balance could get the special paper and the printed forms served as a check that the drawer was a bona fide customer of the Bank of England.

In other words, the late seventeenth century saw three major innovations appear at the same time: governments giving banks licenses to issue bank notes and drawn notes; checks, to allow paper to replace coins; and valued commodities.

The banking system then fuelled the Industrial Revolution, not only enabling easy trading of value exchange through these paper-based systems, but also to allow trade and structure finance through systems that are similar to those we still have today.The oldest Stock Exchange in Amsterdam was launched in 1602 and an explosion of banks appeared in the centuries that followed to enable trade, supporting businesses and governments in creating healthy, growing economies. A role they are still meant to fulfill today. During this time, paper money and structured investment products appeared, and large-scale international corporations began to develop, thanks to the rise of large-scale manufacturing and global connections. So the Industrial Revolution saw an evolution of development, from the origins of money that was enforced by our shared belief systems, to the creation of trust in a new system: paper. The key to the paper notes and paper check systems is that they hold a promise to pay which we believe will be honored. A bank note promises to pay the bearer on behalf wof the nation’s bank and is often signed by that country’s bank treasurer. A check is often reflective of society of the time, and shows how interlinked these value exchange systems were with the industrial age. In summary, we witness three huge changes in society over the past millennia of mankind: the creation of civilization based upon shared beliefs; the creation of money based upon those shared beliefs; and the evolution of money from belief to economy, when governments backed banks with paper.

The Fourth Age of Man: the Network Age

The reason for talking about the history of money in depth is as a backdrop to what is happening today. Money originated as a control mechanism for governments of Ancient Sumer to control farmers, based upon shared beliefs. It was then structured during the Industrial Revolution into government-backed institutions—banks—which could issue paper notes and checks that would be as acceptable as gold or coinage, based upon these shared beliefs. We share a belief in banks because governments say they can be trusted, and governments use the banks as a control mechanism that manages the economy.

So now we come to bitcoin and the Internet age, and some of these fundamentals are being challenged by the Internet. Let us take a step back and see how the Internet age came around.

Some might claim it dates back to Alan Turing, the Enigma machine, and the Turing test, or even further back to the 1930s when the Polish Cipher Bureau were the first to decode German military texts on the Enigma machine. Enigma was certainly the machine that led to the invention of modern computing, as British cryptographers created a programmable, electronic, digital, computer called Colossus to crack the codes held in the German messages.

Colossus was designed by the engineer Tommy Flowers, not Alan Turing—he designed a different machine—and was operational at Bletchley Park from February 1944, two years before the American computer ENIAC appeared. ENIAC, short for Electronic Numerical Integrator and Computer, was the first electronic general-purpose computer. It had been designed by the US Military for meteorological purposes—weather forecasting—and delivered in 1946.

When ENIAC launched, the media called it “the Giant Brain,” with a speed a thousand times faster than any electromechanical machines of its time. ENIAC weighted over 30 tons and took up 167.4 square meters (1800 square feet) of space. It could process about 385 instructions per second.

Compare that with an iPhone6 that can process around 3.5 billion instructions per second, and this was rudimentary technology, but we are talking about seventy years ago, and Moore’s Law had not even kicked in yet.

The key is that Colossus and ENIAC laid the groundwork for all modern computing, and became a boom industry in the 1950s. You may think that surprising when, back in 1943, the then President of IBM, Thomas Watson, predicted that there would be a worldwide market for maybe five computers. Bearing in mind the size and weight of these darned machines, you could see why he thought that way but my, how things have changed today.

However, we are still in the early days of the network revolution and I am not going to linger over the history of computers here. The reason for talking about ENIAC and Colossus was more to put our current state of change in perspective. We are seventy years into the transformations that computing is giving to our world.

Considering it was 330 years from the emergence of steam power to the last steam-power patent, that implies there is a long way to go in our transformation.

Let us first consider the fourth age in more depth as the key difference between this age and those that have gone before is the collapse of time and space. Einstein would have a giggle, but it is the case today that we are no longer separated by time and space as we were before. Distance is collapsing every day, and it is through our global connectivity that this is the case.

We can talk, socialize, communicate, and trade globally, in real time, for almost free. I can make a Skype call for almost no cost to anyone on the planet and, thanks to the rapidly diminishing costs of technology, there are $1 phones out there today, while the cheapest smartphone in the world is probably the Freedom 251. This is an Android phone with a 10.16-centimeter (4-inch) screen that costs just 251 rupees in India, around $3.75. In other words, what is happening in our revolution is that we can provide a computer that is far more powerful than anything before, and put it in the hands of everyone on the planet so that everyone on the planet is on the network.

Once on the network, you have the network effect, which creates exponential possibilities, since everyone can now trade, transact, talk, and target one-to-one, peer-to-peer.

This is why I think of the network as the fourth age of man and money, as we went from disparate, nomadic communities in the first age; to one that could settle and farm in the second; to one that could travel across countries and continents in the third; to one that is connected globally, one-to-one. This is a transformation and shows that man is moving from single tribes to communities to connected communities to a single platform: the Internet.

The importance of this is that each of these changes has seen a rethinking of how we do commerce, trade, and therefore finance. Our shared belief system allowed barter to work until abundance undermined bartering, and so we created money; our monetary system was based upon coinage, which was unworkable in a rapidly expanding industrial age, and so we created banking to issue paper money. Now, we are in the fourth age, and banking is no longer working as it should. Banks are domestic, but the network is global; banks are structured around paper, but the network is structured around data; banks distribute through buildings and humans, but the network distributes through software and servers. This is why so much excitement is hitting mainstream as we are now at the cusp of the change from money and banking to something else. However, in each previous age, the something else has not replaced what was there before. It has added to it. Money did not replace bartering; it diminished it. Banking did not replace money; it diminished it. Something in the network age is not going to replace banking, but it will diminish it. By diminish, we also need to put that in context.

Diminish. Barter is still at the highest levels it has ever been—about 15 percent of world trade is in a bartering form—but it is small compared to the monetary flows. Money in its physical form is also trading at the highest levels it has ever seen—cash usage is still rising in most economies—but it is not high compared to the alternative forms of monetary flow digitally, and in FX markets and exchanges. In other words, the historical systems of value exchange are still massive, but they are becoming a smaller percentage of trade compared with the newest structure we have implemented to allow value to flow.

This is why I am particularly excited about what the network age will do, as we connect one-to-one in real time, since it will create massive new flows of trade for markets that were underserved or overlooked. Just look at Africa. African mobile subscribers take to mobile wallets like ducks to water. A quarter of all Africans who have a mobile phone have a mobile wallet, rising to pretty much every citizen in more economically vibrant communities like Kenya, Uganda, and Nigeria. This is because these citizens never had access to a network before; they had no value exchange mechanism, except a physical one that was open to fraud and crime. Africa is leapfrogging other markets by delivering mobile financial inclusion almost overnight.

The same is true in China, India, Indonesian, the Philippines, Brazil, and many other underserved markets. So the first massive change in the network effect of financial inclusion is that the five billion people who previously had zero access to digital services are now on the network.

A second big change then is the nature of digital currencies, cryptocurrencies, bitcoin, and shared ledgers. This is the part that is building the new rails and pipes for the fourth generation of finance, and we are yet to see how this rebuilding works out. Will all the banks be based on an R3 blockchain? Will all clearing and settlement be via Hyperledger? What role will bitcoin play in the new financial ecosystem?

We do not know the answers to these questions yet, but what we will see is a new ecosystem that diminishes the role of historical banks, and the challenge for historical banks is whether they can rise to the challenge of the new system.

The Fourth Age of Moneykind is a digital networked value structure that is real time, global, connected, digital, and near free. It is based upon everything being connected from the seven billion humans communicating and trading in real time globally to their billions of machines and devices, which all have intelligence inside. This new structure obviously cannot work on a system built for paper with buildings and humans, and is most likely to be a new layer on top of that old structure.

A new layer of digital inclusion that overcomes the deficiencies of the old structure. A new layer that will see billions of transactions and value transferred at light speed in tiny amounts. In other words, the fourth age is an age where everything can transfer value, immediately and for an amount that starts at a billionth of a dollar if necessary.

This new layer for the fourth age is therefore nothing like what we have seen before and, for what was there before, it will supplement the old system and diminish it. Give it half a century and we will probably look back at banking today as we currently look back at cash and barter. They are old methods of transacting for the previous ages of man and moneykind.

This fourth age is digitizing value, and banks, cash, and barter will still be around but will be a much less important part of the new value ecosystem. They may still be processing volumes greater than ever before, but in the context of the total system of value exchange and trade, their role is less important.

In conclusion, I do not expect banks to disappear, but I do expect a new system to evolve that may include some banks but will also include new operators who are truly digital. Maybe it will be Google’s, Baidu’s, Alibaba’s, and Facebook’s; or maybe it will be Prosper’s, Lending Club’s, Zopa’s, and SoFi’s. We do not know the answer yet and if I were a betting man, I would say it will be a hybrid mix of all, as all evolve to the Fourth Age of Moneykind.

The hybrid system is one where banks are part of a new value system that incorporates digital currencies, financial inclusion, micropayments, and peer-to-peer exchange, because that is what the networked age needs. It needs the ability for everything with a chip inside to transact in real time for near free. We are not there yet but, as I said, this revolution is in its early days. It is just seventy years old. The last revolution took 330 years to play out. Give this one another few decades and then we will know exactly what we built.

The Next Age of Moneykind: The Future

Having covered four ages of moneykind—barter, coins, paper, chips—what could possibly be the fifth?

When we are just at the start of the Internet of Things (IoT), and are building an Internet of Value (ValueWeb), how can we imagine something beyond this next ten-year cycle?

Well we can and we must, as there are people already imagining a future beyond today. People like Elon Musk, who see colonizing Mars and supersmart high-speed transport as a realizable vision. People like the engineers at Shimzu Corporation, who imagine building city structures in the oceans. People like the guys at NASA, who are launching space probes capable of sending us HD photographs of Pluto when, just a hundred years ago, we only just imagined it existed.

A century ago, Einstein proposed a space-time continuum that a century later has been proven. What will we be discovering, proving, and doing a century from now?

No one knows, and most predictions are terribly wrong. A century ago they were predicting lots of ideas, but the computer had not been imagined, so the network revolution was unimaginable. A century before this, Victorians believed the answer to the challenge of clearing horse manure from the streets was to have steam-powered horses, as the idea of the car had not been imagined. So who knows what we will be doing a century from now.

2116. What will the world of 2116 look like?

Well there are some clues. We know that we have imagined robots for decades, and robots must surely be pervasive and ubiquitous by 2116 as even IBM are demonstrating such things today. A century from now we know we will be travelling through space, as the Wright Brothers invented air travel a century ago and look at what we can do today.

Emirates now offer the world’s longest nonstop flight with a trip from Auckland to Dubai lasting 17 hours and 15 minutes. We are already allowing reusable transport vehicles to reach the stars and, a century from now, we will be beyond the stars I hope.

Probably the largest and most forecastable change is that we will be living longer. Several scientists believe that most humans will live a century or more, with some even forecasting that a child has already been born who will live for 150 years.

A child has been born who will live until 2166. What will they see?

And we will live so long because a little bit of the machine will be inside the human and a little bit of the human will be inside the machine. The Robocop is already here, with hydraulic prosthetics linked to our brainwaves able to create the bionic human. Equally, the cyborg will be arriving within thirty-five years according to one leading futurist. Add to this smorgasbord of life extending capabilities from nano-bots to leaving our persona on the network after we die, and the world is a place of magic become real.

We have smart cars, smart homes, smart systems and smart lives. Just look at this design for a window that becomes a balcony and you can see that the future is now.

Self-driving cars, biotechnologies, smart networking, and more will bring all the ideas of Minority Report and Star Trek to a science that is no longer fiction, but reality.

It might even be possible to continually monitor brain activity and alert health experts or the security services before an aggressive attack, such as in Philip K. Dick’s dystopian novella Minority Report.

So, in this fifth age of man where man and machine create superhumans, what will the value exchange system be?

Well it will not be money and probably will not even be transactions of data, but some other structure. I have alluded to this other structure many times already as it is quite clear that, in the future, money disappears. You never see Luke Skywalker or Captain Kirk pay for anything in the future, and that is because money has lost its meaning.

Money is no longer a meaningful system in the fifth age of man. Having digitalized money in the fourth age, it just became a universal credit and debit system. Digits on the network recording our taking and giving; our living and earning; our work and pleasure.

After robots take over so many jobs, and man colonizes space, do we really think man will focus upon wealth management and value creation, or will we move beyond such things to philanthropic matters. This is the dream of Gene Rodenberry and other space visionaries, and maybe it could just come true. After all, when you become a multibillionaire, your wealth becomes meaningless. This is why Bill Gates, Warren Buffet, and Mark Zuckerberg start to focus upon philanthropic structures when money and wealth become meaningless.

So could the fifth age of man—the man who lives for centuries in space—be one where we forget about banking, money, and wealth, and focus upon the good of the planet and mankind in general? If everyone is in the network and everyone has a voice, and the power of the one voice can be as powerful as the many, do we move beyond self-interest?

I have no idea, but it makes for interesting questions around how and what we value when we become superhumans thanks to life extending and body engineering technologies; when we move beyond Earth to other planets; and when we reach a stage where our every physical and mental need can be satisfied by a robot.

Comments on this publication