The Liberal International Economic Order, whose creation and operation defined the post-War period in trade andfinance, appears to be entering a period of great uncertainty. This chapter, focusing in particular on international trade, seeks to identify the sources of this change in fundamental changes in the underlying economies of the core members of this order (the transition from an industrial to a post-industrial economy and the globalization of production structures) andthe domestic and international political foundations of that order (domestically the rise of antiglobalist populism, and internationally the emergence of China as a global superpower).

There’s something happening here,

What it is ain’t exactly clear

Stephen Stills (1966) “For What It’s Worth”

After something like 70 years that involved the creation, expansion and consolidation of a global Liberal international economic order (LIEO), we seem to be entering a period of heightened uncertainty about the future of that system. The Doha round is no closer to completion than it was in November 2001 (when the Doha ministerial occurred), two major regional agreements seeking deeper economic integration appear to have stalled (the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership [TTIP] and the Trans-Pacific Partnership [TPP]), and perhaps most striking of all, the UK has started the process of withdrawing from the European Union (potentially undermining the United Kingdom). These events have been associated (one way or another) with the rise of anti-globalist populism in virtually all the core countries of the LIEO. It is far from certain that these current events constitute a fundamental change in the underlying dynamic of globalization, or even if the economic and political events are causally related, but such links are sufficiently plausible that it is worth considering them in some more detail.

Before turning to that task, however, it behooves us to remember just how great a success the post-Depression/post-War LIEO has been. It is now wellunderstood that protection (and the Hawley-Smoot tariff in particular) did not cause the depression (Eichengreen, 1989), but it is equally well-understood that international trade was a key handmaiden of the catch-up growth that characterized the early post-War period in Europe (Eichengreen, 2007). Whereas the first wave of modern globalization relied on weak democratic constraint in core countries, the LIEO of the post-Depression/Post-War period was integrated with democratic constraint via the expanded welfare states in the core countries (Bordo et al., 1999, Ruggie, 1982). In the early postWar years, this was primarily a story about trade. Liberalization of capital controls in the core countries was really only widely adopted in the 1980s, and international migration flows only began to approach those of the late-19th century in the second decade of the 21st century. By contrast, the institutional foundation of Liberal trade, and that trade itself, was extended to more-andmore countries and more-and-more commodities. Over this same time, the institutions supporting Liberal trade evolved to provide increasingly rule-based trading relations (Jackson, 2000, 2006, Weiler, 2001). The jewel in the crown of this system is the institutional structure, particularly the dispute settlement mechanism, created in the Uruguay Round, but legalization extends much more generally (Lang and Scott, 2009, Palmeter, 2000). Perhaps surprisingly, in the face of increased opposition to the LIEO, there have been, as yet, no reversals of commitment to that order.

The case for the existence of a fundamental change in the political-economy of globalization runs through both economic and political change. I will briefly discuss each of those and conclude with some speculation on the future of liberal globalization. In all of this I will focus primarily on international trade.

What Changed?

The Economics

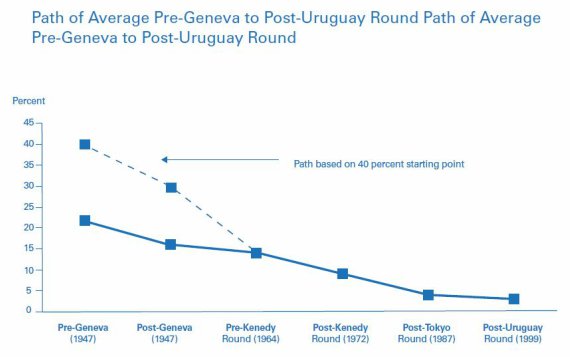

Given the wartime destruction and post-War reconstruction via catch-up to the (primarily North American) technological frontier, the pre-War tariff schedules of the core economies were no longer tightly related to their underlying economies and political-economies. This meant that tariff reduction could be relatively easy. However, the continuing dominance of pre-War elites, and their protectionist policy attitudes, meant that this low-hanging fruit was not so easily harvested. This problem was offset in two ways. Perhaps most importantly, trade policy was associated with Cold War foreign policy. This allowed trade policy to be carried out as a technocratic task associated with the core foreign policy role of the state, and not as a part of the public politics of an electoral democracy. In addition, the technocratic task was conceptualized in terms of “exchange of substantially equivalent concessions”. That is, the logic underlying liberalization was mercantilist, which was politically easier to sell to legislatures still used to viewing trade in those terms. As a result, the core countries reduced tariffs considerably through the first four rounds of GATT negotiations (Bown and Irwin, 2016)—see figure 1.

The GATT/WTO system was constructed by a group of core governments that, while differing widely among themselves, were characterized by a set of fundamental similarities: they were all: capitalist democracies, constructing welfare states, built on industrial economies. I will discuss changes to the democratic welfare state below, here I consider changes in the industrial economies. All the original core members of the GATT/WTO system were what, at the time and for many years after, were called “advanced industrial economies” (often just “AICs”). During the early GATT years, negotiations focused on reducing tariffs on manufactured goods (agricultural goods were excluded by the core countries for domestic political reasons), and developing countries were excused from most GATT disciplines under the belief that they required “special and differential” treatment (Irwin et al., 2008, Subramanian and Wei, 2007). Because all of the core countries viewed manufactures as fundamental to their own macroeconomic dynamic, and the broad sector in which they possessed strong comparative advantage, exchange of concessions on manufactures trade was relatively easy. The GATT process was rendered even easier by the fact that much of the trade within the core was intra-core (minimizing “leakage” to non-core economies), by intra-industry. The latter not only made comparison of concession magnitudes even easier, but was believed to have lower adjustment costs than inter-industry tariff cuts. We have already noted that the exhaustion of the relatively easy liberalizations associated with the early Rounds made negotiations more difficult, we now note that transformation of the core economies constitutes an even more fundamental challenge. We focus here on two major changes in the economic context of trade negotiation: post-modernization of the core; and the emergence of generalized global production.

The economic core of post-modernization is the transition to an economy whose fundamental dynamic is driven by the service sector.

Like the transition from an agrarian to an industrial political-economy, the transition to a post-industrial political economy is complex and completely disturbing to the social, political and economic arrangements of the industrial political-economy. These challenges would be difficult to manage in a closed economy, but the intimate relationship between post-modernization and globalization has made the politics of globalization both confusing and incendiary. The economic core of post-modernization is the transition to an economy whose fundamental dynamic is driven by the service sector, reflected in part by an increased share of employment in that sector. This is driven by technologies that permit more efficient (labor-saving) production of manufactures, but is supported and accelerated by technologies that permit extensive global sourcing. That is, industrial employment is reduced on both the local efficiency and the global outsourcing margins. While this certainly promotes a shift in the economies of the LIEO core to service production in which those economies have a comparative advantage, with all the benefits in terms of aggregate income emphasized by trade economists, the shift from manufacturing to services involves adjustment costs that are both larger and less well understood than the shifts within manufacturing that characterize adjustment to earlier liberalizations.

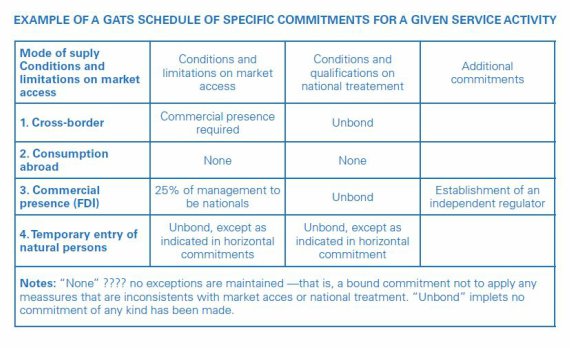

Just as services are essential to the post-Modern economy in general, they are essential to the post-Modern global economy and the relationship of the core trading economies to the global economy. The fundamental problem is that services are not well-enough understood, and certainly not well-enough measured, to be treated under the exchange of concessions mechanism that worked so well for trade in manufactures (Francois and Hoekman, 2010). This would be problematic even if the main barriers to trade in services were tariff barriers, but a more fundamental problem derives from the fact that the main barriers to integration of global service markets are not generally trade barriers at all, but national regulations adopted for reasons more or less unrelated to trade policy. Thus, not surprisingly, the Uruguay round, so successful in advancing the programme of creating a legal framework for trade in manufactured goods, was unable even to agree on what “trade in services” meant exactly (Drake and Nicolaïdis, 1992, Panizzon et al., 2008). The service agreement (GATS—the General Agreement on Trade in Services), which identifies four “modes” of trade in services, while technically part of the single-undertaking involved only very weak commitments (Adlung and Roy, 2005, Borchert et al., 2014, Hoekman, 1996) (see Table 1).

The third major shock to the global economy, along with post-Modernization and fully global production, is the emergence of China as a great political and economic, power. Following decades of aggressively egalitarian and anti-market policy, China began to reform its economy in the very late-1970s, with more thoroughgoing encouragement of market-oriented policies in the late-1980s and 1990s, ultimately involving accession to the WTO in December 2001 (Brandt and Rawski, 2008, Naughton, 2017). This resulted in literally unprecedented growth— averaging 9.7% per year from 1978 through 2016 (World Bank data online). This was accompanied by a major transformation of the economy as China became the largest manufacturing economy and the largest exporter in the world, with much of this increase coming in the last decade. As with Europe’s growth following the Second World War, international trade played a major role in supporting that transition. However, as was also the case with other high growth economies in transition (primarily in Asia and Eastern Europe), and unlike the case of post-War Europe, much of this export growth was associated with participation in global value chains anchored on the US, Europe or Japan (Baldwin, 2016). Thus, post-Modernization, global value chains, and Chinese export growth are all part of a single complex that is transforming both national and global political-economies. Not only do each of these involve pressure to adjust in fundamental ways in both the national and international economies, but the complex relationship between them raises difficult questions about what form such adjustment should take. Not surprisingly, these economic pressures interact with changed political circumstances to make the future even more uncertain.

The Politics

One of the keys to post-War liberalization was the general acceptance of trade policy as a component of Cold War foreign policy (Nelson, 1989). That, along with support for deeper integration in Europe, the creation of a general LIEO (anchored on the Bretton Woods institutions and the GATT), were seen as fundamentally political, not fundamentally economic. As such, domestically it was dominated by the Executive and treated as an essentially technocratic policy, not part of general partisan competition. Furthermore, in the U.S.House of Representatives, trade legislation was handled by the Committee on Ways and Means which, at the time, was dominated by centrists. The association of increasingly Liberal trade with the strong economic performance of the postWar “Golden Age” led to a broad acceptance of economic, as well as political, arguments in favor of Liberal trade by political elites. With the end of the Cold War and the collapse of Congressional system for managing trade, in particular the weakening of Ways&Means in the face of the twin shocks of a post-Watergate reform revolt and the public humiliation of Chair Wilbur Mills, this broad elite consensus, along with continued Executive commitment, sustained political support for the programme of trade liberalization through the multilateral GATT, and then WTO, process. That Executive commitment reached a high point under Jimmy Carter, and his Trade Representative Robert Strauss, but has declined since then—generally more rapidly under Republican Presidents than Democrats. In the absence of the Cold War, the institutional protection of trade in Congress, and an Executive committed to the multilateral liberalization process, it has proven difficult to provide leadership for the WTO process facing the challenges identified in the previous section.

It is an axiom of political economic analysis that material (i.e. economic) well-being, and changes therein, are the fundamental drivers of politics (politics over economic issues such as globalization and post-Modernization). This axiom certainly draws credibility from the rhetoric around the public politics of those issues. More specifically, as far as the public politics of globalization and post-Modernization are concerned, the primary measure of the costs and benefits of economic change, and policies responding to such change, is labor market performance—their effects on employment and wages. In evaluating these effects, it is important to distinguish between the long-term, structural, effects of such changes and the short-term, adjustment, effects. The former should inform structural policies (e.g. trade policies) while the latter should inform strategies to cope with adjustment costs.

In labor markets of the post-War Golden Age, moderately educated, primarily white, male, workers found manufacturing employment at wages that could support a middle-class lifestyle. Extensive unionization and strong growth in the leading manufactured goods sectors underwrote high wages and job stability. Additionally, the development of the welfare state promised income insurance in the face of economic downturn. This is the compromise of “embedded Liberalism” that many in the post-War era believed had found a way to balance the demands of capitalism and democracy (Blyth, 2002, Shonfield, 1965). At the international level, this involved a balance between sovereignty and interdependence (Finlayson and Zacher, 1981, Ruggie, 1982). The maintenance of these balances meant that there was little political interest in opposition to a broadly market conforming domestic economic policy or a relatively tight link between the domestic economy and the global economy. A breakdown in either of those balances could call the entire system into question. Thus, just as the complex of factors discussed above (post-Modernization, global production, and China) have made the functioning of the multilateral system more difficult, they have also changed the political environment within which that system operates.

Instead of core labor being concentrated in industrial production, as in the Modern labor market, the post-Modern labor market tends to be divided into skilled and unskilled service labor (Emmenegger, 2012). In both cases, labor needs to be flexible in the face of changing demands, with skilled service labor requiring general skills that can be applied across a wide range of sectors, and unskilled service labor filling relatively short-tenure jobs that require little in the way of specialized skill (Wren, 2013). The former jobs pay a premium, while the latter do not and the rising demand for general skills is having a significant effect on the income distribution (Autor, 2014, Goos et al., 2014, Michaels et al., 2013). Post-

Modernization thus hits the low-skill middle class in two ways: rising productivity allows firms to substitute capital for labor in manufacturing, resulting in a relatively constant output of manufactures while the share of labor in manufacturing has dropped dramatically; and the jobs available for those workers are relatively low-paid service jobs. Furthermore, given that service jobs, both low and high skilled, generally have a minimal requirement of brute strength, women have been increasingly able to compete on equal terms with men for such jobs (Iversen and Rosenbluth, 2010). On the one hand, this has resisted the rise in household inequality as the two-income household has increasingly become the norm, but on the other hand, men have found themselves in much more competitive labor markets. Finally, whether high or low skilled, the post-Modern labor market is characterized by considerable uncertainty as well (Brown et al., 2006).

It is possible that unions and welfare states could have resisted trends like these, but both of these institutions have been buffeted by post-Modernization and politics. Unions are at their strongest when workers with similar labor market traits are concentrated in large workplaces and governments are broadly supportive. We have already noted that fewer and fewer workers are employed in such workplaces, as service jobs involve smaller firms with more flexible workforces, while the large firms that remain are increasingly characterized by global workforces. Neither of these make union organization easier. In principle, union decline could be resisted if governments were committed to supporting them, but the reverse has been more common throughout the (post-)industrial world. There is a broad, though perhaps not terribly deep, consensus among economists that the fundamental driver of post-Modernization is technological change, though it is clear that, as with the post-War Golden Age, globalization has played an important supporting role (Desjonqueres et al., 1999, Van Reenen, 2011).

The post-modern labor market tends to be divided into skilled and unskilled service labor.

Where the literature on the economic effects of post-Modernization is overwhelmingly focused on structural consequences (e.g. changes in national income and its distribution) and very little concern with adjustment, the literature on response to globalization (trade and migration in particular) includes extensive research on both structural change and adjustment, though it is not always clear in the presentation of research to which of these a given piece of research speaks. In thinking about the labor market effects of trade, we need to distinguish between two sorts of shock: a large increase in trade with low wage countries; and a change in the structure of trading relations (i.e. the dramatic increase in global organization of production). The standard textbook account of a national economy’s response to a change in trading conditions contains the main tools needed to understand the structural (i.e. long-run) effects associated with the first of these shocks.1 Since 1990, the core (post-)industrial economies have seen sizable falls in the relative price of manufactured goods exported by developing and transition economies and these have been associated with large increases in the volume of imports from those countries (Krugman, 2008, see text around figures 1 and 7). Since these goods would have been importables before the 1990s, and thus these price changes do not involve a negative terms-of-trade shock, the effect on national income should be strongly positive. That is, the rich countries get a price cut for the goods they are importing and can specialize even more in production of their exportables. Of course, the same models that underwrite this conclusion also tend to suggest that there could be sizable distributional effects from factors used intensively in the production of importables to factors used intensively in the production of exportables.2 In fact, this relationship underlies much of the research on the political economy of trade policy. While most attempts to measure the size of this effect produce rather small numbers, something in the neighborhood of 10-20% of the rise in the skill premium as of 2006, Krugman (2008) has pointed out that these estimates are based on data that are both too short to convincingly allow the adjustment to the long-run implied by the theory and too early to incorporate the large increases in imports from developing countries and countries in transition.

In the same paper, Krugman (2008) makes the valuable point that the global organization of production has made the analysis more difficult. The construction of price series and implicit factor flows proceeds from industry definitions that involve a relatively high degree of aggregation. What this means is that we may observe considerable north-south intra-industry/intra-firm trade in goods whose production, in fact, use quite different input combinations (i.e. are actually different commodities). This, then interferes with empirical inference based on the standard model. On the one hand, in terms of a multi-cone version of the standard model, this implies equilibrium relative factor price differences (that is, trade with economies with quite different relative factor prices need not imply any pressure for factor-price equalization); but, on the other hand, if one is thinking in terms of implicit trade in factors, the implicit flow of unskilled labor may be considerably larger that we are usually estimating.3Thus, at least at this point, while the direction of the effect of trade on the skill premium seems unproblematic, the magnitude is far from clear. Furthermore, given that the rich, core economies have adjusted to the price changes/trade volumes in question, any reversal of those changes would produce a new round of redistributions (and a fall in aggregate income). Before turning to the issue of adjustment, we should note a different effect of globally organized production. Baldwin (2016) argues that the new millennium has witnessed the emergence of a qualitatively new globalization—Baldwin’s “second-unbundling”—associated with global organization of production involving construction of value chains that involve exchange of northern technology for less expensive southern inputs. While this is essentially consistent with the Krugman story we have just noted, it also implies a more unstable allocation of tasks across the global economy, affecting both skilled and unskilled workers. Along with, and to a considerable extent indistinguishable from, post-Modernization, the 21st Century labor markets are likely to be characterized by declining returns to unskilled work and greater employment/income uncertainty throughout the value chain/task structure. As we shall see below, this is could create a foundation for the emergence of populist political movements.

While the direction of the effect of trade on the skill premium seems unproblematic, the magnitude is far from clear.

One of the difficulties of learning from research on trade and labor markets is the, more-or-less unrecognized, difference between trade and labor economists in the focus of their research. Not only does this difference, and the fact that it is unrecognized by trade and labor economists, lead to miscommunication between professional economists, but it is also confusing to consumers of that research. In simple terms, trade economists tend to focus on long-run structural questions, while labor economists focus on adjustment problems. While it is widely understood among economists of all flavors that structural policy (e.g. trade policy) is an inappropriate response to adjustment problems, it is unquestionably the case that adjustment problems are far more politically significant than long-run, Stolper-Samuelson type, distributional issues. A sizable literature on adjustment developed in response to the trade shocks in the 1980s showing, among other things, that these adjustment costs are heterogeneous across sectors and workers, falling particularly hard on older workers in declining sectors (e.g. Kletzer, 2002). As concerns with Japan, and the “Newly Industrialized Countries” (the NICs) faded, so did research on this topic, but it came back with renewed strength in the face of China’s entry into the world trading system as a major participant. With better data and more modern econometric techniques, and a “China shock” of literally unprecedented magnitude, labor economists have been able to compellingly identify large adjustment costs (Autor et al., 2016a). Much of the rhetoric around this work suggests that the consensus in the research on the 1980s shows that trade was not a major source of the long-run rise in the skill-premium (i.e. the long-run fall in return to unskilled labor), was wrong. Unfortunately, that conclusion rests, first and foremost, on a simple confusion: the earlier conclusion was about a long-run fall in the skill-premium, the current work speaks to potentially large adjustment costs between long-run equilibria. The point is not that these adjustment costs are insignificant. Far from it. As with job and income loss of any kind, these costs are highly significant to the people experiencing them. Furthermore, given that these adjustments are essential to reaping any gains from trade, the recognition that the people bearing the costs are precisely the people generating the gains, creates a sound normative case for adjustment assistance. That is, there is no moral system I can think of that provides a warrant for punishing the small group of people who underwrite a gain to the many.

Whether high or low skilled the post-modern labour market in characterised by considerable uncertainty.

Unfortunately, moral arguments of this sort are rarely politically effective. However, the implications of deteriorating income distribution and increased job risk for political stability are a matter of general concern. In recent years, anti-globalist populist movements have achieved striking success. While the roots of these movements appear to be more associated with the dislocations associated with post-Modernization, the electoral success of these movements does appear to be associated with large trade shocks, the China shock in particular (Autor et al., 2016b, Colantone and Stanig, 2017, Jensen et al., 2017, Rodrik, 2017). As with our discussion of structural and adjustment issues in the economic response to trade shocks, it is important to be clear that this work shows a link between political activity (primarily right-wing populist activity) and adjustment to the China shock, not changes in the long-run structure of the economy. The problem from a political perspective is that it has proven essentially impossible to compellingly distinguish between these two sources of change. It is certainly the case that the rise of right-wing populism precedes Baldwin’s (2016) second unbundling by more than a decade and seems to be more associated with post-Modernization than globalization (Iversen and Cusack, 2000, Iversen, 2005). Furthermore, the link between change in economic status and participation in populist politics is not terribly strong (Inglehart and Norris, 2016, Mudde, 2007). Unfortunately, a foreign threat is always a better political foil than technological change. In the past, and independent of the source of social, political and economic stress, relatively unskilled workers were more protected by unions and welfare states, but both of these institutions have been weakened by post-Modernization and globalization. Furthermore, both of these institutions were organically related to Modernism and, with the passing of the Modern age, it is not at all clear that these could be simply reconstructed even if there was the political will to do so.

Where Are We Going?

The international political economy that has delivered ¾ of a century of peace and prosperity to the countries that constitute its core is at a transitional moment. In the global and national political economies that make up the system face political and economic challenges driven, in large measure, by a fundamental transformation of the Modern industrial economy on which those political economies were built. Some of these challenges are manifested in adjustments to change in the global economic relations that played a major role in that order. The experience of the inter-War years reminds us that, while globalization is reversible, the consequences of such reversal are, at a minimum, unpredictable and, more than likely, dire. In addition to the challenges that stem from structural changes in the economy and the effect of those changes on the political arrangements that supported the embedded Liberalism of the post-War LIEO, we face, for the first time since the end of the First World War, the question of whether the system must also deal with a collapse of leadership. In the earlier period, Britain was no longer capable of providing such leadership and the US, the only nation with the political and economic capacity to take up that leadership, produced a vacuum that helped destroy the first Liberal globalization (Kindleberger, 1986, Skidelsky, 1976). While it is clear that collective commitment to a semi-legalized order is an effective substitute for hegemony, it is far from clear that such an order can survive withdrawal from that commitment by a nation with hegemonic capacity. The question here is whether Trumpism is an aberration that will be reversed, or whether it constitutes an ongoing threat of the kind posed by Britain in the inter-War period. Ironically, as it did in the inter-War years, Little Britain seeks to undermine the European Union, the other potential world power committed to domestic capitalism and democracy, and to global Liberalism. At the same time, as in the inter-War years, there is a rising power, China, which seems unready to take up fully the mantle of global leadership. In the case of China, there is also the question of its commitment to domestic capitalism and democracy, or to global Liberalism. The global Liberal order clearly needs to make room for China, but whether that order can survive China if the US and the EU turn their back on that order is very much in doubt. This is a period that needs leadership and we can only hope that such leadership comes from a new Roosevelt, and not a new Hitler or Stalin.

Bibliography

Adlung, Rudolf and Martin Roy (2005). “Turning Hills into Mountains? Current Commitments under the General Agreement on Trade in Services and Prospects for Change.” Journal of World Trade, V.39 #6, 1161-94.

Autor, David H. (2014). “Skills, Education, and the Rise of Earnings Inequality among the “Other 99 Percent”.” Science, V.344-#6186, 843-51.

Autor, David H.; David Dorn and Gordon H. Hanson (2016a). “The China Shock: Learning from Labor Market Adjustment to Large Changes in Trade.” Annual Review of Economics, V.8-#1.

Autor, David H.; David Dorn; Gordon H. Hanson and Kaveh Majlesi (2016b). “Importing Political Polarization? The Electoral Consequences of Rising Trade Exposure,” NBER Working Paper, #22637.

Baldwin, Richard E. (2014). “WTO 2.0: Governance of 21st Century Trade.” The Review of International Organizations, V.9-#2, 261-83.

____ (2016). The Great Convergence: Information Technology and the New Globalization. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

Blyth, Mark (2002). Great Transformations: Economic Ideas and Institutional Change in the Twentieth Century. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Borchert, Ingo; Batshur Gootiiz and Aaditya Mattoo (2014). “Policy Barriers to International Trade in Services: Evidence from a New Database.” The World Bank Economic Review, V.28-#1, 162-88.

Bordo, Michael; Barry J. Eichengreen and Douglas A. Irwin (1999). “Is Globalization Today Really Different from 100 Years Ago?,” in R. Lawrence and S. Collins eds, Brookings Trade Forum–1999. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution, 1-71.

Bown, Chad P. and Douglas A. Irwin (2016). “The Gatt’s Starting Point: Tariff Levels Circa 1947,” NBER Working Paper, #2782.

Brandt, Loren and Thomas G. Rawski (2008). China’s Great Economic Transformation. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Brown, Clair; John C. Haltiwanger and Julia I. Lane (2006). Economic Turbulence: Is a Volatile Economy Good for America? Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Chandler, Alfred D. (1977). The Visible Hand: The Managerial Revolution in American Business. Cambridge, Mass.: Belknap Press.

____ (1994). Scale and Scope: The Dynamics of Industrial Capitalism. Cambridge, Mass.: Belknap Press.

Colantone, Italo and Piero Stanig (2017). “The Trade Origins of Economic Nationalism: Import Competition and Voting Behavior in Western Europe,” BAFFI CAREFIN Centre Research Paper, #2017-49.

Deardorff, Alan V. (2000). “Factor Prices and the Factor Content of Trade Revisited: What’s the Use?” Journal of International Economics, V.50-#1, 73-90.

Deardorff, Alan V. and Robert W. Staiger (1988). “An Interpretation of the Factor Content of Trade.” Journal of International Economics, V.24-#1, 93-107.

Desjonqueres, Thibaut; Stephen Machin and John van Reenen (1999). “Another Nail in the Coffin? Or Can the Trade Based Explanation of Changing Skill Structures Be Resurrected?” The Scandinavian Journal of Economics, V.101-#4, 533-54.

Drake, William J. and Kalypso Nicolaïdis (1992). “Ideas, Interests, and Institutionalization: “Trade in Services” and the Uruguay Round.” International Organization, V.46-#01, 37-100.

Eichengreen, Barry J. (1989). “The Political Economy of the Smoot-Hawley Tariff.” Research in Economic History, V.12, 1-43.

____ (2007). The European Economy since 1945: Coordinated Capitalism and Beyond. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Emmenegger, Patrick ed. (2012). The Age of Dualization : The Changing Face of Inequality in Deindustrializing Societies. Oxford ; New York: Oxford University Press.

Ethier, Wilfred J. (1984). “Higher Dimensional Issues in Trade Theory,” in R. W. Jones and P. Kenen eds, Handbook of International Economics. Amsterdam: North-Holland, 131-84.

Finlayson, Jock A. and Mark W. Zacher (1981). “The GATT and the Regulation of Trade Barriers: Regime Dynamics and Functions.” International Organization, V.35-#4, 561-602.

Francois, Joseph F. and Bernard Hoekman (2010). “Services Trade and Policy.” Journal of Economic Literature, V.48-#3, 642-92.

Francois, Joseph F. and Douglas R. Nelson (2017). “Trade Volumes and Wages: A Note,” ms,

Goos, Maarten; Alan Manning and Anna Salomons (2014). “Explaining Job Polarization: Routine-Biased Technological Change and Offshoring.” American Economic Review, V.104-#8, 2509-26.

Hoekman, Bernard (1996). “Assessing the General Agreement on Trade in Services,” in W. Martin and L. A. Winters eds, The Uruguay Round and the Developing Countries. Washington, DC: The World Bank, 327-64.

Inglehart, Ronald W. and Pippa Norris (2016). “Trump, Brexit, and the Rise of Populism: Economic Have-Nots and Cultural Backlash,” Havard Kennedy School of Government Research Working Paper, #16-026.

Irwin, Douglas A.; Petros C. Mavroidis and A. O. Sykes (2008). The Genesis of the GATT. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Iversen, T. and T. R. Cusack (2000). “The Causes of Welfare State Expansion – Deindustrialization or Globalization?” World Politics, V.52-#3, 313-49.

Iversen, Torben (2005). Capitalism, Democracy, and Welfare. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Iversen, Torben and Frances McCall Rosenbluth (2010). Women, Work, and Politics: The Political Economy of Gender Inequality. New Haven Conn.: Yale University Press.

Jackson, John H. (2000). The Jurisprudence of GATT and the WTO: Insights on Treaty Law and Economic Relations. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

____ (2006). Sovereignty, the WTO and Changing Fundamentals of International Law. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Jensen, J. Bradford; Dennis P. Quinn and Stephen Weymouth (2017). “Winners and Losers in International Trade: The Effects on US Presidential Voting.” International Organization, V.71-#3, 423-57.

Jones, Ronald W. and Jose Scheinkman (1977). “Relevance of 2-Sector Production Model in Trade Theory.” Journal of Political Economy, V.85-#5, 909 35.

Kindleberger, Charles Poor (1986). The World in Depression, 1929-1939. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Kletzer, Lori G. (2002). Imports, Exports, and Jobs: What Does Trade Mean for Employment and Job Loss? Kalamazoo, Mich.: W.E. Upjohn Institute for Employment Research.

Krugman, Paul R. (2008). “Trade and Wages, Reconsidered.” Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, V.2008, 103-37.

Lang, Andrew and Joanne Scott (2009). “The Hidden World of WTO Governance.” European Journal of International Law, V.20-#3, 575-614.

Leamer, Edward E. (2000). “What’s the Use of Factor Contents?” Journal of International Economics, V.50-#1, 17-49.

Michaels, Guy; Ashwini Natraj and John Van Reenen (2013). “Has ICT Polarized Skill Demand? Evidence from Eleven Countries over Twenty-Five Years.” Review of Economics and Statistics, V.96-#1, 60-77.

Mudde, Cas (2007). Populist Radical Right Parties in Europe. Cambridge University Press Cambridge.

Naughton, Barry (2017). The Chinese Economy: Adaptation and Growth. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Nelson, Douglas R. (1989). “The Domestic Political Preconditions of US Trade Policy: Liberal Structure and Protectionist Dynamics.” Journal of Public Policy, V.9-#1, 83-108.

Palmeter, David (2000). “The WTO as a Legal System.” Fordham International Law Journal, V.24 #1&2, 444-80.

Panagariya, Arvind (2000). “Evaluating the Factor Content Approach to Measuring the Effect of Trade on Wage Inequality.” Journal of International Economics, V.50-#1, 91-116.

Panizzon, Marion; Nicole Pohl and Pierre Sauvé (2008). GATS and the Regulation of International Trade in Services. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Rajan, Raghuram G. and Luigi Zingales (2000). “The Governance of the New Enterprise,” in X. Vives ed Corporate Governance: Theoretical and Empirical Perspectives. Cambridge: Cambride University Press, 201-27.

____ (2001). “The Firm as a Dedicated Hierarchy: A Theory of the Origins and Growth of Firms.” Quarterly Journal of Economics, V.116-#3, 805-51.

Rodrik, Dani (2017). “Populism and the Economics of Globalization,” NBER Working Paper, #23559.

Ruggie, John G. (1982). “International Regimes, Transactions, and Change: Embedded Liberalism in the Post-War Economic Order.” International Organization, V.36-#2, 379-415.

Shonfield, Andrew (1965). Modern Capitalism: The Changing Balance of Public and Private Power. London: Oxford University Press.

Skidelsky, Robert JA (1976). “Retreat from Leadership: The Evolution of British Economic Foreign Policy, 1870-1939,” in B. Rowland ed Balance of Power or Hegemony: The Interwar Monetary System. New York: New York University Press, 149 89.

Stolper, Wolfgang and Paul A. Samuelson (1941). “Protection and Real Wages.” Review of Economic Studies, V.9-#1, 58-73.

Subramanian, Arvind and Shang-Jin Wei (2007). “The WTO Promotes Trade, Strongly but Unevenly.” Journal of International Economics, V.72-#1, 151-75.

Van Reenen, John (2011). “Wage Inequality, Technology and Trade: 21st Century Evidence.” Labour Economics, V.18-#6, 730-41.

Weiler, Joseph H.H. (2001). “The Rule of Lawyers and the Ethos of Diplomats: Reflections on the Internal and External Legitimacy of WTO Dispute Settlements.” Journal of World Trade, V.35-#2, 191 207.

Wren, Anne ed. (2013). The Political Economy of the Service Transition. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Yates, JoAnne (1989). Control through Communication: The Rise of System in American Management. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. Source: Bown and Irwin (2016)

Notes

1 Current research has dramatically expanded the textbook model to include monopolistic competition, firm heterogeneity and unemployment. The first two tend to increase gains from trade without much changing the analysis of distributional effects, while the latter makes the analysis more complex without fundamentally changing the main long-run message of the textbook model.

2 This is the implication of the Stolper-Samuelson (1941) theorem. This is a bit delicate. That theorem strictly applies to a world with 2 goods and 2 factors (the Heckscher-Ohlin-Samuelson model). With more goods and factors, dimensionality matters to the identity of the gainers and losers, and to whether the gains and losses are real –i.e. unambiguous relative to all prices of consumption goods (Ethier, 1984, Jones and Scheinkman, 1977). The key, in any case is the relative price change, not the volume of trade, though we would expect those to go together.

3 For what it’s worth, I don’t find the use of factor flows particularly compelling. In addition to the problems raised by Leamer (2000) and Panagariya (2000), Francois and Nelson (2017) argue that the inference engine developed by Staiger and Deardorff (Deardorff, 2000, Deardorff and Staiger, 1988) fails a simple check of the empirical validity of the key causal link in that inference engine.

Comments on this publication