The worst economic downturn that virtually any of us can remember has already led to large drop-offs in various sorts of cross-border flows (1). International trade is predicted to drop by 9–10% in 2009. Foreign direct investment (FDI) may decline by as much as 45% compared to 2008 figures, which were already 15% lower than in 2007. International air traffic is predicted to be 5% lower during 2009 than 2008. Anecdotal accounts suggest that even immigration flows are down: thus, emigration from Mexico to the US dropped 13% in the first quarter of 2009 versus the same period in 2008, with more Mexicans leaving the US than coming in. And so on.

Such changes and the developments underlying them have, naturally, nonplussed those who believed in a world that was already completely integrated or rapidly—and irreversibly—approaching that end-state, e.g., believers in the so-called flat or flattening world. Yet others have overreacted by convincing themselves and others that the world is rapidly de-globalizing, with no end to that trend in sight.

With all that is at stake, it seems useful to look more carefully at the data and respond to the crisis based on a more realistic view of where we are today and what the future is likely to entail. Acknowledging a world that is bumpy—or as I will explain more precisely, semiglobalized—instead of flat is essential to actually thinking constructively about how to deal with a bump. To make the point that semiglobalization is indeed a stable frame of reference upon which intelligent responses to recent fluctuations can be built, I will begin by discussing some recent data on a cross-border flow that has experienced particularly large drop-offs: foreign direct investment. I will then address the implications of the crisis and the likely post-crisis environment for companies’ international strategies, focusing on what it means for each of the three fundamental ways that companies can create value across borders: adaptation (which may need extra emphasis over the medium term), aggregation, and arbitrage. And while I will defer to others the role of making formal predictions, particularly about the timing of the macroeconomic recovery, I will raise one crucial wildcard—protectionism—which business leaders should factor into their strategies as a possibility, while at the same time vigorously opposing it.

The metatheme I will return to throughout this paper is the importance—particularly now—of accounting for and genuinely respecting differences. Doing so can, in addition to helping companies bolster their performance, also help defend the system of relatively open markets that underpins our collective prosperity. Experienced international executives know that while this looks simple at first, it can be frustratingly difficult to really get right. Therefore, I will conclude with a practical framework to help managers see cross-country differences more clearly and focus on the most relevant differences for their own companies and industries.

Cross-border investment in a crisis

Reconsider the cross-border flow that has shown a particularly big percentage decline: foreign direct investment. To begin with some aggregate data, UNCTAD estimates, in its World Investment Report, that FDI fell from $2 trillion in 2007 to $1.7 trillion in 2008, and is likely to range between $0.9 and $1.2 trillion in 2009. These are such drastic declines that they have prompted a shift in the conversation, from the celebration of complete cross-border integration to despair about deglobalization.

But before these fluctuations whipsaw us, we should look more closely at the data. From a cyclical perspective, we know that investment in fixed capital has historically declined two to four times as fast as output during downturns (Ghemawat 1993, 2009). Declines in FDI tend to be even larger than those of overall fixed capital investment because most FDI is accounted for by cross-border mergers and acquisitions (M&As), which exhibit great sensitivity to shrinking corporate profits and plummeting stock prices, and which should therefore be expected to fall particularly steeply given the acute financial crisis as well as the real downturn that has hit the world economy. And indeed, cross-border M&A activity is what really seems to have collapsed: it declined between 2007 and 2008 by a bit more than the total decline observed in FDI flows, and was running at a fraction of previous levels in the first six months of 2009!

Such declines may be excessive—Keynes’s point about “animal spirits”—but they are certainly not unprecedented. The 2000–1 period supplies an example from earlier in the same decade: while gross domestic product (GDP) declined by less than 1% over that period, the stock market crashed—and cross-border M&A declined from $1.1 trillion in 2000 to $0.6 trillion in 2001. Largely as a result, total FDI went down by 40%, from $1.4 trillion to $0.8 trillion, from one year to the next.

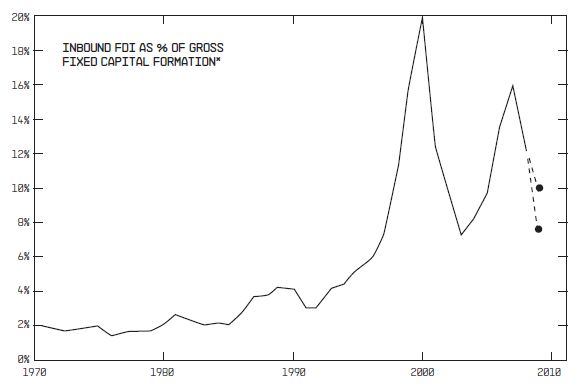

Figure 1:

*The two estimates for 2009 are upper and lower bounds. Source: UNCTAD, World Bank Development Indicators, estimates.

A second way of gaining perspective on these numbers is to divide them by other variables so as to construct proxies for FDI-intensity. The most commonly used base in this regard is GDP. FDI has declined from 3.6% of GDP in 2007 to 3.1% in 2008 and around 2% in 2009. Again, while this is a very large decline, it is smaller—and slower—than the drop-off from 4.4% of GDP in 2000 to 2.6% in 2001 (and to 1.9% in 2002 and 1.5% in 2003). Or in other words, precedents for the drop-off along this dimension can, once again, be found earlier in the decade.

My own preferred normalization is to look at how large total FDI flows are in relation to gross global fixed capital formation because this permits a (rough) answer to the question of how much of all the capital being invested around the world is being deployed by companies outside of their home countries. Figure 1 tracks the evolution of this ratio over four decades.

Several points are worth emphasizing about this longitudinal perspective:

- In 2008, the ratio of FDI to gross fixed capital formation amounted to 12.3%.

- The predictions for 2009 are for a ratio in the 7–10% range

Based on these predictions, the average for 2000–9 (11.7%) is still almost twice as high as the average for the 1990s (6.4%), and several times higher than the averages for the 1980s (2.7%) and the 1970s (1.7%).

While these substantial variations over time are interesting, what is even more so is a time-invariant property: despite all the (pre-crisis) rhetoric about “investment knowing no boundaries,” the ratio of FDI to gross fixed capital formation falls very far short of that perfect-integration benchmark. If the sources of capital really did not matter at all for where it is deployed, one would expect the cross-border component of total investment to exceed 90% (2). Even at the (recent) peak in 2000, the observed ratio amounts to just a small fraction of this 90%+ level.

A measured read of international investment trends must also reflect the fact that plummeting aggregate flows at the global level mask significant growth in cross-border investment in particular industries and countries. For example, FDI increased in 2008 in the food, beverage, and tobacco industries where cross-border M&A value rose 125% and in the primary sector (up 17%). Developing countries also saw more robust FDI inflows and outflows versus developed countries—they grew in 2008—but are projected to decline in 2009. Even among the developed countries there were some bright spots. Thus, Spain’s inward FDI rose 133% in 2008, after declining 24% in 2007 while Spain’s outward FDI declined 20%, versus a 3.5% decline in 2008. (For comparative perspective, European Union inward and outward FDI declined 40% and 30% respectively in 2008 after having surged 43% and 70% respectively in 2007). In addition to highlighting the fact that there is still growth taking place, these examples also serve to illustrate the general volatility and cyclicality of FDI flows adverted to above.

The state of the world: still semiglobalized

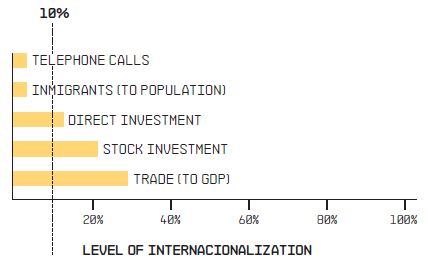

My broader point in reviewing the latest FDI data was to illustrate that the while the world is seeing extreme fluctuations on some metrics of international integration, it remains far from the endpoints of either complete globalization or deglobalization, a point with important strategic implications as I will explain in the next section. And FDI isn’t an isolated, unrepresentative example. Look at Figure 2, which summarizes data on internationalization along five dimensions that include, in addition to FDI, categories related to information flows (telephone calls), people flows (immigrants), pure financial flows (stock investment), and product flows (exports to GDP).

Figure 2: Measures of cross-border integration. The measures used are defined as follows:

– Telephone calls = international calling minutes as percentage of total calling minutes.

– Immigrants (to Population) = stock of longterm international migrants as percentage of world population.

– Direct investment = foreign direct investment flows as percentage of gross fixed capital formation.

– Stock investment = foreign investors’ share of stock market capitalization (weighted average across countries by share of global capitalization).

– Trade (to GDP) = global exports of merchandise and nonfactor services as percentage of GDP.

Sources for most of the data are discussed in Redefining Global Strategy, p. 12; the stock investment data are for 2005 and are drawn from Piet Sercu and Rosanne Vanpee, “Home Bias in International Equity Portfolios: A Review,” University of Louvain Department of Accountancy, Finance and Insurance Working Paper AFI 0710 (August 8, 2007).

As you can see, the level of internationalization along these dimensions is still relatively limited. It averages roughly 10% over the years in the 2000s for which data are available as of this writing (September 2009). And even the “outerperformer,” the trade-to-GDP ratio shown at the bottom of the figure—probably recedes most of the way back toward 20% if you adjust for double-counting (3). As a result, “Globaloney”—Clare Booth Luce’s original riposte to Wendell Wilkie’s visions of One World more than half a century ago—is probably still a good comment on assertions that the world is already globalized or rapidly becoming so. And there are many people who exaggerate in this regard. Thus, the respondents to an online poll conducted (before the crisis) by Harvard Business Review estimated the levels of internationalization of the variables listed in Figure 2 at 30% rather than close to 10%! (4). I have also surveyed many other groups with these questions, with broadly similar results.

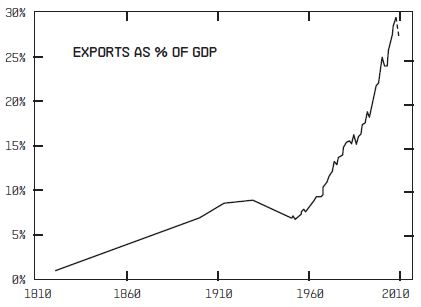

The present downturn has also resurrected—in some quarters—Globaloney’s opposite, which I have termed Localoney: the belief that globalization is rapidly receding and the future belongs only to nation states and their resurgent governments. This view, of course, is also inconsistent with the data, but it must be addressed seriously because the tendency to extrapolate and overreact to current trends is always strong. For some additional data consider Figure 3, which shows exports as a percentage of GDP going as far back as the early 1800s. Despite the recent downturn, this indicator, like FDI, is nowhere close to approaching its historic lows (and in fact is still near its all-time high, unlike FDI-intensity, which reached comparable highs before the First World War, in the Age of Empire).

Figure 3: Source: Angus Maddison, World Trade Organization, World Bank World Development Indicators, estimates.

Furthermore, most analysts project that cross-border flows will start growing again with macroeconomic recovery—perhaps even reversing the recent declines in fairly short order. The World Bank projects that trade flows will recover swiftly, reversing the 10% estimated decline in 2009 in only two years. And UNCTAD forecasts that FDI inflows will resume growing in 2010 and, with growth rates close to the high end of the ranges that it is predicting, may exceed their 2008 level by 2011.

Of course, the actual flows will depend on the timing and pace of the recovery as well as on the wildcard I mentioned before—protectionism. But what should be clear by this point is that the world is very far from either complete globalization or deglobalization, and is hence most unlikely to reach either endpoint in the foreseeable future. The image I like to use to illustrate this is of a tumbleweed blowing across the plains of the Midwestern United States. It may cover some distance—speed up, slow down, and even change direction—but it is far more likely to remain somewhere in the middle of the country than to end up on either coast. Looking forward, levels of cross-border integration may increase, stagnate, or even suffer a sharp reversal, but given the parameters of the current situation, it seems unlikely that increases will any time soon yield a state in which the differences or barriers between countries can be ignored. Or that decreases could lead to a state in which the similarities or bridges can be forgotten about. Thus, semiglobalization supplies a more attractive reference frame for thinking through global strategy than either getting caught up in near-term fluctuations or relying on very long term, very iffy predictions.

The dangers of Globaloney and Localoney

Recognizing the reality of semiglobalization complicates decision-making but can help improve its quality because Globaloney and Localoney are not just harmless dietary supplements: they lead to decisions that can be dangerous to a company’s and a society’s health.

Let us start by looking at the effects of Globaloney. Managers who buy into the idea that the world is “flat” tend to make errors that reflect their overestimation of cross-border integration, underappreciation of cross-country differences, and in many cases even lack of respect for countries themselves as entities and their political and social institutions. Evidence in this regard is supplied by the positive correlation between (over)estimates of cross-border integration and assent to frankly size-based propositions such as in the online survey carried out by Harvard Business Review cited above. Of the respondents, 64% agreed that the “truly global company should aim to compete everywhere,” and 58% agreed that “Globalization tends to make industries more concentrated.”

Both beliefs fit well with a worldview in which the differences between countries do not matter much. As Bruce Kogut pointed out twenty years ago, in the absence of such differences, the answer to the question of “what is different when we move from a domestic to an international context… [is] simply that the world is a bigger place, and hence all economies related to the size of operations are, therefore, affected” (Kogut 1989). But they seem far removed from current realities.

• Ubiquity may not be a sensible target given international differences. And even if it were, it would require enormous geographic broadening by all but a handful of global giants, restricting interest in it to the very long run. Consider, for instance, all US companies with foreign operations in 2004—themselves less than 1% of all US companies. The largest fraction operated in just one foreign country, the median number in two, and 95% in fewer than two dozen (5). And none of this has changed since the mid-1990s!

• Increased concentration as a result of globalization commands believers in the anti-globalization movement as well as among managers—but lacks empirical basis. Data on the concentration of production in the hands of the five largest competitors in 18 global/globalizing industries show no general increase between the late 1980s and the late 1990s: concentration increased in some but was offset by decreases in others (Ghemawat and Ghadar 2006). And a number of the industries reported as experiencing increases in concentration over that period (e.g., automobiles and oil production) actually experienced much larger decreases in the prior decades that recent increases have only partially offset.

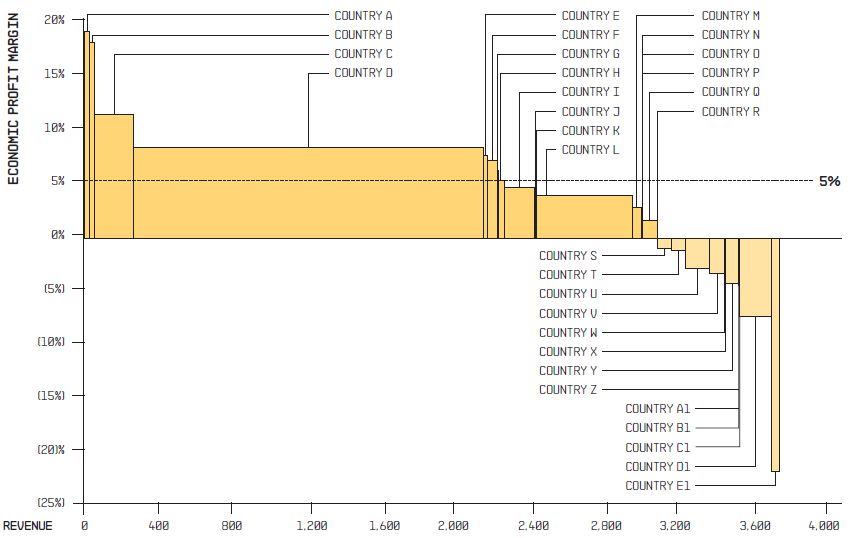

Given such unwarranted sizeism, it is unsurprising that many firms’ performance in the countries in which they do opt to compete is often uneven and, to a significant extent, even unprofitable. Some indications of the extent of the problem are provided by data that Marakon Associates analyzed at my request. They summarized their findings as follows:

We found that half of the [large] companies we have looked at (8 out of 16) have significant geographic units that earn negative economic returns… [We] know from our clients that their profitability by geography has stayed fairly stable over time unless they have specifically targeted action at specific countries/regions.

Figure 4 provides a fairly typical—pre-crisis—example of this type of problem. In 2005, roughly one-fifth of this company’s revenues were in country markets that destroyed economic value.

Figure 4: Economic profits by country for a fast moving consumer goods company. (Source: Marakon Associates.)

In addition to its economic suboptimality, the sizeism or even imperialism associated with Globaloney risks fueling protectionism. Think about how foreign publics (and politicians) view companies that act and talk as if it is their right and destiny to be king of the heap. How would Robert Woodruff’s (CEO of Coca-Cola from the 1920s until the early 1980s) words sound to the ears of a proud citizen of a small but rapidly developing (non-Western) country: “In every country in the world, [Coca-]Cola dominates. We feel that we have to plant our flag everywhere, even before the Christians arrive. Cola’s destiny is to inherit the earth” (6). Or how might one expect Westerners to react to the CEO of a small Indian software services company—the large ones know better—declaring India the emerging information technology superpower whose companies will wipe out all the rest? When companies fail to be sensitive to such cross-country differences, they not only shoot themselves directly in the foot, but they also engender a backlash that fuels calls for protectionism and threatens to narrow their range of future strategy options. In other words, when business leaders buy into Globaloney and make no bones about doing so, they risk provoking publics and politicians to try Localoney instead.

Although Localoney has not been nearly as fashionable in recent years, many companies started with and remain stuck with such attitudes in practice if not by proclamation—and many of them treat the current crisis as confirmation that their approach is in fact the right one. Others have lapsed into Localoney as a reaction to excesses of Globaloney. Reconsider the example of Coca-Cola. Until the 1980s, despite the triumphalism of CEO Woodruff’s approach (which one wit termed “Coca-Colonization”), Coke’s local operations were more or less independently managed. It was Woodruff’s successor, Roberto Goizueta, who took over in 1981, who bought into Globaloney—particularly the idea then current that customers everywhere increasingly wanted the same thing—and began aggressively to centralize and standardized Coke’s operations. In 1996, he declared that “the labels international and domestic, which adequately described our business structure in the past, no longer apply. Today our company, which just happens to be headquartered in the United States, is truly a global company.” Consumer research, creative services, TV commercials, and most promotions were managed from Coke’s headquarters in Atlanta.

When Goizueta died unexpectedly in 1997, his successor Douglas Ivester stayed the course. Excessive centralization and standardization combined with the Asian crisis to lead to growth shortfalls, falling market capitalization (down $70 billion from its peak), and fraying relations with governments and bottlers (who were starting to find Coke “overbearing”). Ivester was quickly fired.

The next CEO, Douglas Daft, took localization to the opposite extreme— Localoney. As he put it in January 2000, “No one drinks globally. Local people get thirsty and go to their retailer and buy a locally made Coke.” He downsized headquarters and shifted decision-making authority to the field. He announced that no more global advertisements would be made and put ad budgets and creative control in the hands of local executives, who were understandably delighted—but also underprepared. As a result, quality suffered even more than scale economies. And volume growth slowed to even lower levels than under Ivester. Localoney was short-lived, as by 2002 the Wall Street Journal reported that the “‘think local, act local’ mantra is gone. Oversight of marketing is returning to Atlanta.” By 2004, Daft was gone too.

Under Daft’s successor, Neville Isdell, Coke moderated its strategy in ways that better reflect the reality of semiglobalization, and performance improved. In Isdell’s view, “the pendulum swung too far over” under his immediate predecessors. He began to emphasize innovation over economies of scale, and put international and domestic back into separate organizations. The direction Coke will take under new CEO Muhtar Kent remains to be seen, but his experiences heading various regional divisions and ultimately Coke’s whole international business—as well as running Efes Beverages in Turkey—lead one to expect some degree of sensitivity to cross-country differences.

To summarize, Globaloney and Localoney can clearly both result in poor performance. Globaloney leads to unrealistic estimates of scale economies, excessive standardization, and pursuit of growth that often turns out to destroy shareholder value. And its imperialistic aspects can fuel the anti-globalization backlash and contribute to the threat of protectionism. Localoney gives up altogether on cross-border leverage, and so its costs are to be reckoned with more in terms of opportunity costs than out-of-pocket costs—which makes them less likely to register but no less real.

Adjusting global strategy to respond to the crisis

The reality of semiglobalization provides a stable frame of reference within which meaningful analysis can substitute for slogans, enabling companies to avoid the kinds of mistakes referenced above. Strategies rooted in semiglobalization involve integrated consideration of both local and cross-border interactions—of the barriers and the bridges between countries. In my 2007 book Redefining Global Strategy I described three fundamental ways that companies can create value across borders in a world where differences still matter: the AAA strategies of adaptation, aggregation, and arbitrage. Adaptation refers to adjusting to cross-country differences to provide local responsiveness. Aggregation involves overcoming cross-country differences to achieve scale/scope economies that extend across national borders. Arbitrage exploits differences—as in buying low in one country and selling high in another. My general prescription was for managers to select a combination of these strategies, tailored to their company’s own industry, position, capabilities, and intent.

That continues to be my general prescription. Looking at a range of possible post-crisis futures, cross-country differences seem unlikely to disappear. In a few respects, the direct result of the crisis may be to decrease differences, but in many—possibly most—others, they are likely to increase instead.

To be more specific about a few major effects, the crisis is, first of all, accelerating the shift of the world’s economic activity and dynamism toward the major emerging markets, and particularly toward Asia. This increases the diversity that companies have to deal with if they want to tap into markets that are still growing rapidly. Secondly, governments around the world are becoming more active participants in national economies. Given the diversity of political systems and the policies being enacted, this increases the degree of cross-country difference (the administrative distance or barriers between countries) that strategies need to address. Thirdly, protectionism is a major wildcard. Companies need to be prepared for the possibility of new restrictions on trade, investment, migration, and potentially even information flows—while working, with governments, to take actions to guard against protectionism. Fourthly, there seems to be heightened potential for economic turbulence and in particular, for large swings in exchange rates—the most worrisome risk being that of a collapse of the dollar—as global imbalances are worked through. This has very different implications for different companies (depending on home country, industry, and company factors) so it will not be addressed further here.

From the standpoint of global strategy, these observations imply that while the AAA strategies continue to constitute the relevant strategy set, it may, in the medium term, make sense for most firms to put comparatively more emphasis on adaptation relative to aggregation and arbitrage—although this should ultimately depend on each firm’s industry, history and strategy. It is also important to note that it can take years for companies to make meaningful shifts in this regard, so they should not be undertaken without careful consideration of longer term plans and expectations for industry evolution. The rationale for strengthening adaptation is that becoming responsive to local conditions is robust in case of protectionism, helps to address the growing role of governments, and is necessary in many cases for participating in the growth that is available in emerging markets. In addition, becoming more respectful of differences can actually help lower the likelihood of protectionism. That said, aggregation—short of complete standardization or one-size-fits-all—is still important because most multinationals try to leverage some element of scale or scope across markets to create advantages for themselves over local firms (in contrast to adaptation, which is mostly aimed at minimizing disadvantages versus local firms). And arbitrage remains important as well because of the continued differences between countries but has become more politically sensitive in the present environment so companies need to be more careful in pursuing such strategies, and to put contingency plans in place.

The rest of this section will address in some detail how companies can strengthen adaptation and will then provide briefer discussions of aggregation and arbitrage.

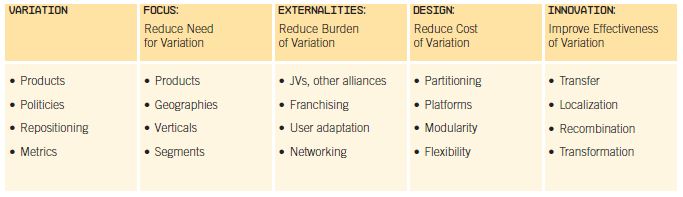

Adaptation encompasses a broad range of levers and sublevers that companies can use respond to cross-country differences, of which variation is perhaps the most obvious: if local markets have different preferences, offer them different products or services. But such variation is costly and in the extreme results in operations that are so different across countries that there is no value gained by keeping them together in a single company. Smart adaptation therefore typically involves not only appropriate decisions about the amount of variation but adroit application of one or more complementary sub-strategies such as focus, externalization, design, and innovation that help reduce the costs of variation. These levers and sublevers are summarized in Table A and elaborated below.

Table A: Levers and sublevers for adaptation.

Variation encompasses changes in products, but also in policies, business positioning, and even metrics (e.g., target rates of return). Product variation is conceptually straightforward, but what is notable is that even products that are supposedly standardized have to be varied a great deal—such as Coca-Cola, which is formulated with varying sweetness around the world. And the case of Coke in China and India provides a vivid example of why true variation usually requires much more than just product variation. Like most foreign multinationals, Coke entered these markets with a focus on wealthier, urban consumers who were already familiar with the company’s brand and were prepared to pay high prices for its products. But under Isdell, it conducted a major repositioning to move beyond skimming the top of these markets, by lowering price points and margins, reducing costs by indigenizing inputs, and greatly increasing availability particularly in rural areas. This type of repositioning to broaden market penetration is often an important step for foreign multinationals aspiring to become true mass players in the large emerging markets such as China and India.

The trouble with relying exclusively on variation as a lever for adaptation is that it increases complexity. One, often complementary, lever for keeping complexity under control is to focus or purposefully narrow scope so as to reduce the extent of differences encountered and the amount of adaptation required. Thus, Spanish banks and other multinationals focused geographically—on Latin America—in their early internationalization. This was partly because of the wave of privatization and deregulation in that region in the first part of the 1990s, but also reflected a desire to keep cultural and administrative distance manageable by dealing with Spanish-speaking ex-colonies with similar legal and other institutions. BBVA, in particular, has pursued the cultural thread beyond the political borders of Latin America with a strategy that targets the Spanish-speaking niche market in the (southern) United States as a good fit with its operations in Mexico, where it owns the country’s biggest bank, Bancomer. And Zara is able to do well in international retailing with an approach that is quite standardized because of segment rather than geographic focus: in fast fashion, the customer in Barcelona does care about what the customer in Tokyo is wearing, and there is a premium on quick response that plays to Zara’s strengths. And so on.

The next lever in Table A, externalization, has some affinities with focus. However, instead of narrowing scope, externalization purposefully splits activities across organizational boundaries to reduce the internal burden of adaptation. Externalization subsumes sublevers such as joint ventures (JVs) and other strategic alliances, franchising, user adaptation, and networking. JVs and strategic alliances have long been known to be comparatively attractive when the amount of cultural and administrative distance to be bridged is large: they can provide access to local knowledge that would otherwise be hard to purchase, to links in the local value chain that would otherwise be inaccessible, or to local connections, including political ones, and associated benefits. (Of course, JVs/alliances also impose their own costs and risks, including financial insecurity, lack of control, and misuse of intellectual property, so they are no panacea.) And in many businesses, especially in services, in key markets such as China and India, JVs are still the only way multinationals are allowed to enter. Juxtaposing these reasons against the changes in the post-crisis world cited above leads one to expect a post-crisis surge in JVs. While it is too early to obtain systematic data, a Google Trend analysis of news items on international JVs does indeed show a very sharp jump, to unprecedented levels, in the first few months of 2009!

Design decisions can also deliberately reduce the cost of variation. Common, interrelated methods of designing business systems to ease variation include partitioning, platforms, modularization, and flexibility. To cite a simple but very well-executed example of partitioning, McDonald’s splits choices into those where local adaptation is feasible and those where adaptation would compromise system performance—following a roughly 20% local and 80% global rule in this regard. And for an approach to flexibility—cost-effective variation over time—that is currently attracting attention, consider selective de-automation: a phenomenon I first encountered working a few years ago with a major consulting firm and that is described systematically in a study of changing production processes in global auto components that is sponsored by the Sloan Foundation. To quote from the preliminary findings:

The most notable thing about the production processes that were initially transferred from high wage regions is that they were highly capital intensive with significant degrees of automation…. As experience in the low wage environments began to accumulate, and as those markets themselves began to develop, it became clear that a reduction of the levels of automation in the low wage areas could have significant advantages: …[it] could prove to be efficient at both large volume production and in more variegated batch production, and in shifting from one large volume job to another…. [While] there is still a great deal of experimentation about this “de-automation”… it is already becoming clear to many producers that the gains in flexibility that their offshore operations have achieved through de-automation can actually be implemented within their own factories in high wage regions. (Herrigel 2007)

Finally, some of the levers and sublevers discussed above—such as repositioning and (re)design—could also be characterized as instances of innovation. While innovation is conceptually a very broad lever, cross-border differences often restrict the scope of innovation making it useful to distinguish among transfer, localization, recombination, and transformation (arrayed in terms of increasing radicality). Selective de-automation, for example, has progressed a significant part of the way through this cycle and reminds us, among other things, that experience may yield innovations or insights in one context that can be transferred to others, and that such useful innovations need not originate in a firm’s largest or most advanced markets. Of course, to note these points is not to solve the difficult challenges that managers face in harnessing knowledge pools in emerging markets, where more and more of the technical manpower on which most companies rely will be located. Doing so is likely to require disrupting the traditional “home-first” organization of innovation structures within multinational companies—itself just one functional manifestation of a broader set of changes that are probably required if multinationals from developed countries are to focus on and compete more effectively in big emerging markets.

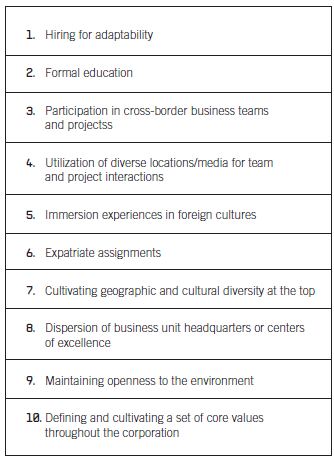

That brief discussion of innovation starts to touch on the globalization and adaptability of mindsets, which continues to be seen as the major challenge by many companies. The basic point is that how well a company does at adjusting to differences depends not only on which adaptation levers it pulls but also on the kind of company it is: companies with international experience and traditions of cosmopolitanism are expected to adapt more effectively to a given amount of distance than their more cloistered counterparts. And while one cannot choose one’s history, one can work on globalizing a company’s mindset, as illustrated by the roster of potential initiatives listed in Table B.

Table B: Building adaptability

My broader purpose in listing all of these levers and sublevers here is to show that there are many ways that companies can adapt to differences, rather than just one or two blunt instruments such as product reformulation or decentralization. Given the importance of strengthening adaptation both to improve business performance and to defend against protectionism, I hope most managers will find within these lists some ideas that can help their own companies respond better to cross-country differences.

Aggregation, since it often involves pulling in the direction opposite to adaptation, is, by the logic laid out above, likely to be somewhat less rather than more in evidence in the medium-term. But as noted above, it remains fundamental to many companies’ attempts to create advantages over locally-based competitors. It can also confer advantages over other global competitors if they fail to exploit such opportunities themselves. Consider, for example, Ernst & Young, the fourth largest global accounting firm, which has significantly outperformed its larger rivals (so far) in 2009. The company attributes its success in large part to its 2008 aggregation of its 87 country practices in Western and Eastern Europe, the Middle East, India, and Africa into a single EMEIA area, with more than 60,000 people (close to one-half the corporate total) led by a single area managing partner and executive team (Hughes 2009). Among other things, this has let Ernst & Young shift staff between the countries as needed. Note that (increased) aggregation may be fundamental to the consolidation required as part of many firms’ restructuring efforts (which are discussed further in the next section).

Arbitrage also continues to be a fundamental strategy for competing across borders. The shift of manufacturing to locations with lower labor costs is no longer a new phenomenon, and the effects can be truly massive. Thus, the savings that Wal-Mart generates by procuring tens of billions of dollars of goods from China in particular, significantly exceed its profits from operating international stores—on a much smaller capital base—and have become critical to its pursuit of a low-cost strategy in the US (which still accounted for three-quarters of its $400 billion in revenues over 2008–9). And the offshoring of services, while less developed, is growing even more rapidly, with IT services leading the way. From 2004 to 2008 global offshore IT services revenues grew from about $30–35 billion to $89–93 billion. In India, this explosive growth propelled the IT Services and Business Process Outsourcing (BPO) sectors from 1.2% of GDP in 1998 to 5.8% in 2009 (7). According to an analysis by CLSA Asia Pacific in 2006, 25% of India’s near term GDP growth would come from IT and BPO services and multiplier effects from those industries’ growth.

Thus arbitrage has become very important to both buyers and sellers. However, it is also extremely sensitive from a political and societal perspective. Consider one pre-crisis poll conducted by the Chicago Council on Foreign Relations in December 2006: 76% of respondents agreed with the statement, “Outsourcing is mostly a bad thing because American workers lose their jobs to people in other countries.” Only 21% believed “outsourcing is mostly a good thing because it results in lower prices in the US, which helps stimulate the economy and create new jobs” (8)—which is what the scientific evidence actually seems to indicate. Of even greater concern, when asked in July–August 2008, “Do you think the recent economic expansion in countries like China and India has been generally good for the US economy, or bad for the US economy, or had no effect on the US economy?,” 62% of respondents answered “bad” versus only 14% answering “good” (9).

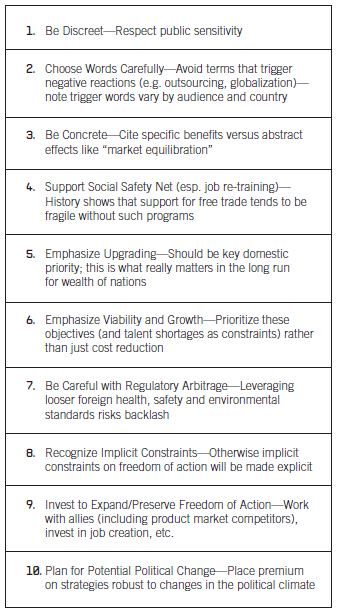

As firms focus on sensitizing themselves to local difference, it’s also likely that they’ll want to be more careful about pursuing certain strategies that exploit these differences, particularly offshoring. Clearly the traditional Chimerica model—whereby the US imports large volumes of cheap Chinese goods—is unlikely to persist. When announcing new investments, major US companies have recently stressed their domestic nature—witness Intel talking about its new semiconductor labs or GE talking about new wind turbine facilities. The same consumer backlashes and protectionist impulses that may make adapting to differences more important in the next few years may also make wage-arbitrage between localities less desirable. That does not mean abandoning arbitrage strategies, but it does suggest more sensitivity and discretion in their pursuit—and the institution of back-up plans in case arbitrage does become less viable in the medium-term. To be more specific, Table C presents ten tips I have developed to help companies address arbitrage-sensitivity.

Reevaluate, restructure, reinvest

Beyond adjusting global strategies to better account for differences, companies should also take a careful look at their portfolios of country markets with respect to their economic value added (i.e., profitability after at least a rough accounting for the cost of capital employed). How do your prospects really look in each country after factoring in the downturn? The need for such analysis may seem obvious, but the most alarming finding, for me at least, from the pre-crisis online survey of Harvard Business Review readers, was that 88% of the respondents thought of global expansion basically as an act of faith—a “strategic imperative”—rather than as an alternative to be evaluated. This belief was probably nourished by a climate of rising asset prices in which many companies essentially thought of globalization as one long asset accumulation play with relatively little risk involved. But now that the asset bubble has burst, we need to actually evaluate performance, because as indicated in Figure 4, a significant portion of the global operations of many firms subtracts value instead of adding it.

Especially since ubiquity is seldom the right target, such an analysis may lead to exiting weaker markets where the prospects do not justify continued investment. And of course, downturns (and their immediate aftermath) are more obvious times to restructure or exit weaker markets than upturns. Nokia, for example, announced in November 2008 that it was exiting the mobile handset market in Japan (except for its high-end Vertu brand) after years of investment yielded only a meager ~1% market share (versus ~40% globally). Exiting the world’s fourth largest market must not have been an easy decision for Nokia but it’s a realistic one considering the unique (idiosyncratic) preferences of highly demanding Japanese consumers, different standards, and the dominance of local firms.

By the same token, while evaluating markets and restructuring where appropriate, don’t forget to invest in the areas where there are promising opportunities. Recognize that there are known biases toward overreaction in such matters—companies tend to cut too much in a downturn, just as they overinvest in a bubble. In my 1993 Sloan Management Review article, “The Risk of Not Investing in a Recession” (expanded and reissued in March 2009), I highlight the interplay between financial risk and competitive risk. In normal times, the bearishness of the former tends to (or is supposed to) complement the bullishness of the latter. But the balance between the two seems to break down at business cycle extremes. Specifically, at the bottom of the business cycle, companies seem to overemphasize the financial risk of investing at the expense of the competitive risk of not investing. Once-in-a-cycle errors of this sort can create a lasting competitive disadvantage.

Consider again the example of Nokia. Exiting from Japan’s handset market didn’t imply a general pullback of strategic investments. In 2009, Nokia made a range of investments in new technologies, particularly around value added services that can be delivered via mobile phone platforms. Kraft presents another interesting example. In 2008, Kraft announced plans to restructure internationally by focusing on 10 key brands in five categories across 10 primary international markets (four “growth engines” and six “scale markets”). But in September 2009, Kraft launched a $16.7 billion bid for Cadbury that would significantly add to and accelerate the transformation of its business portfolio. While Kraft’s initial offer proved inadequate and will likely have to be raised for the transaction to go through—it is still pending, as of this writing—downturns generally do also increase the likelihood of being able to acquire distressed assets on the cheap. To cite just one such cross-border deal, Fiat agreed to buy 35% of Chrysler for nothing more than promises to share small car technology and its global dealer network. Fiat’s price was much less than the $7.2 billion Cerberus Capital Management paid for its 80% stake in the company less than two years earlier, not to mention the tens of billions of dollars that Daimler Benz paid for control of Chrysler in 1998.

Table C: Ten tips for dealing with arbitrage-sensitivity

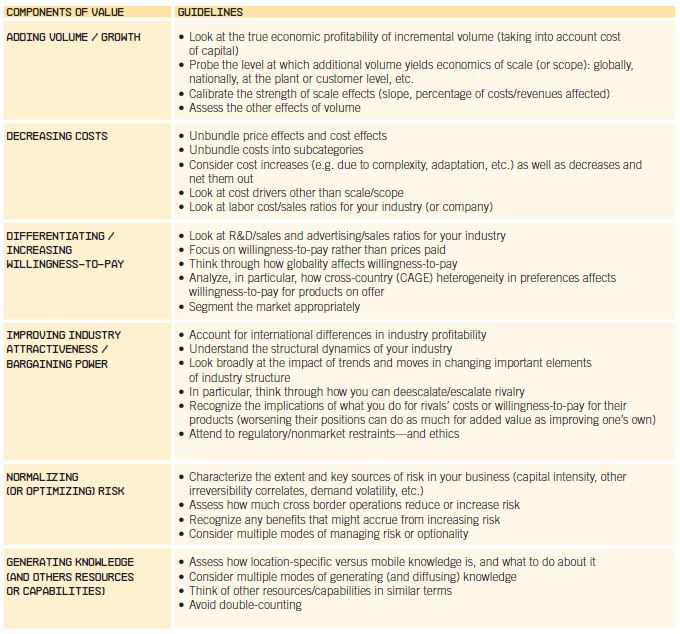

In evaluating where to cut and where to invest, it helps to lay out very clearly how a particular operation is intended to add economic value to the overall enterprise. The ADDING Value scorecard shown in Table D can help structure this analysis. It parses the assessment of international business strategy into the individual levers via which value is created or destroyed, each of which is individually manageable and thus amenable to careful (and in many cases quantitative) analysis.

Table D: ADDING value scorecard.

Amp up the diplomacy

Thus far I have addressed companies’ strategies for addressing the downturn in the various markets in which they operate. Companies also need to look beyond the confines of the market to influence outcomes. In particular, with the role of government on the rise, firms should actively pursue a well-thought out program of what academics call “nonmarket strategy” but that might also roughly be characterized as corporate diplomacy.

Many companies still approach nonmarket strategy by exception: apart from dealing with specific nonmarket issues as they come up, there is little sustained effort to engage with them. A purely reactive, ad hoc approach, while never defensible, makes even less sense in an environment in which governments are becoming more rather than less important in varied roles—as buyers, suppliers, competitors, owners, regulators, collectors of taxes, and so on—making it imperative that top managers, in particular, spend more of their time on nonmarket issues. Instead of the knee-jerk insistence that markets should hold full sway over social and economic policy, this will require showing more sensitivity to—and acceptance of—regulatory, legal, political, social, and cultural differences. And it will also require business leaders to anchor the case against protectionism: if they do not, it is not clear who will.

While a full treatment of business-government relations is clearly beyond the scope of this article, I will offer a few suggestions. Firstly, map out all the players, remembering, in particular, that governments—even in countries without multiparty democracy—are rarely monolithic. Secondly, evaluate each player’s objectives vis-à-vis your own. Are they strictly opposed, different but not precisely opposite, or non-rivalrous/reinforcing? Identify friends as well as foes on this basis. Thirdly, map out the relationships among the players and assess who has leverage over whom, and how much. Fourthly, identify the range of instruments through which you and your company (together with appropriate allies) can influence outcomes. Fifthly, decide how assertive to be—is it better to be out front on the issue or to engage in quieter behind-the-scenes diplomacy? And finally, as you formulate your plan of action (and negotiating strategy), pay attention to legal and social constraints on nonmarket strategy, which are often substantial.

Beyond government, business also needs to address itself to the public at large. The need for this seems particularly urgent in the United States where a recent survey ranked business executives tenth out of ten occupational categories, with only 21% of respondents having a favorable view of them (compared to 23% of respondents for having a favorable view for lawyers, the second-least-favored category; and scores in the 70–80% range for very respected professions such as the military, teaching, etc). While the situation may look somewhat better elsewhere, the point is that we are at a moment where market capitalism and private business enterprise are being subjected to significant, sustained attack without recent precedent. Dealing with this attack is likely to require fundamental changes in behavior rather than just attempts to engage with civil society and nongovernmental organizations.

A particularly important objective of engaging with both governments and civil society is to combat protectionism. Recent reports by the Global Trade Alert and the World Trade Organization highlight a raft of protectionistic measures in 2009 that range from higher tariffs to immigration restrictions, state aid funds, and export subsidies—and that greatly outnumber laws liberalizing trade. Businesses need to push to make sure that the case for opening up and against protectionism is fully understood and internalized in public perceptions and the political dialogue. What is at stake is not only the preservation of gains we have already been able to achieve by opening up but also the pursuit of additional opportunities to open up—opportunities that are, in a semiglobalized world, still very large.

How to see relevant differences more clearly

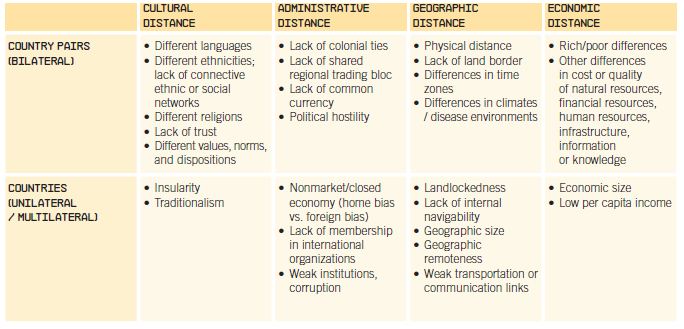

Throughout this article, I have focused on the need for companies to be more sensitive to cross-country differences. But as experienced international executives know, it is sometimes very hard to actually pick up on the key differences, even when one has a chance to get beyond the usual look-alike airport terminals, chain hotels, and office towers. To help managers improve their acuity in this regard, I have developed the CAGE Distance Framework, shown in Table E. The four categories of differences for which CAGE is an acronym are termed “distances” to emphasize the fact that countries should be thought of as part of networks and hence analyzed based on both bilateral and unilateral factors.

Table E: CAGE framework at the country level.

Astute readers will also note that different types of distance matter more or less in different industries (and even for different companies within industries). To help managers focus on the most important differences for their own industries, I have summarized the factors that make particular industries more or less sensitive to each type of distance in Table F.

Table F: Industry sensitivity to CAGE distances.

The CAGE framework can be used, most obviously, to help assess where to compete. And that is the use to which a number of companies are putting it: thus, in a clear response to the crisis, Dr. Reddy’s, the largest Indian-owned pharmaceutical firm, recently used CAGE to help scale back from 50 markets to fewer than 20. But the framework is also meant to be of broader use in helping companies think different by helping make differences visible and reminding multinationals of their liabilities relative to local competitors as well as their advantages.

Conclusions

The post-crisis world is still being formed and we still have opportunities to shape the reality in which we will have to operate. Based on all the available evidence, semiglobalization will remain the stable frame of reference it has been in recent years. While some metrics of cross-border integration such as trade are presently retreating after having set new highs, we remain far from a world of either negligible or complete globalization. Thus, fundamental techniques such as understanding differences via the CAGE framework and the crafting of strategies based on carefully tailored combinations of adaptation, aggregation, and arbitrage are still robust in the present environment and the foreseeable future.

My fundamental prescription for the present times is to think different. Not just to think different-ly—but to think different, in the sense of becoming more sensitive to and genuinely welcoming of local differences. Thinking different is the best way to improve business performance while at the same time fostering the openness that is fundamental to sustaining our collective prosperity.

Notes

- The data that follow are drawn from the official compilations by the WTO (trade), UNCTAD (foreign direct investment), and IATA (air traffic).

- The perfect-integration benchmark is equal to one minus the fractional Herfindahl concentration ratio of gross fixed capital formation by country, for reasons that the interested reader can work out. The calculation here is based on the most recent data available from the World Bank’s World Development Indicators, most of which are for 2005.

- One problem is the focus on revenues rather than value added—e.g., shipments of car parts from the US to Canada, with cars being shipped back.

- This survey was designed by me and run by Harvard Business Review, to which I am very grateful.

- Computations are based on Bureau of Economic Analysis data kindly carried out at my request by Raymond J. Mataloni, fall 2007.

- The Cola Conquest, video directed by Irene Angelico, Ronin Films, 1998.

- Nasscom.

- http://www.americanprogress.org/issues/2007/01/wtprw.html.

- http://www.pollingreport.com/trade.htm.

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to Steven Altman for extensive help in updating and elaborating the material in this paper, and to the Division of Research at IESE Business School for the generous support of my ongoing work on globalization and global strategy. The paper also draws heavily on my earlier work, particularly my book, Redefining Global Strategy, which contains detailed citations as well as discussion of many of the points made more briefly here.

Bibliography

Ghemawat, P. “The Risk of Not Investing in a Recession.” Sloan Management Review (March 2009).

—. Redefining Global Strategy. Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press, 2007.

Ghemawat, P., y F. Ghadar. “Global Integration ? Global Concentration.” Industrial & Corporate Change 15 (2006): 595-623.

Herrigel, G. Interim Substantive Report on Global Components Project. Chicago: University of Chicago, October 16, 2007, 3–5.

Hughes, J. “New International Structure Helps E&Y Weather Downturn.” The Financial Times, October 1, 2009, 18.

Kogut, B. “A Note on Global Strategies.” Strategic Management Journal 10, 389 (1989): 383–89.

Sercu, P., and R. Vanpee. Home Bias in International Equity Portfolios, working document AFI 0710. Louvain: University of Louvain, Department of Accountancy, Finance, and Insurance, August 8, 2007.

Comments on this publication