The outbreak of the novel coronavirus 2019-nCoV in China, which has already spread to other countries, has rekindled fears of a major pandemic among the public, but the truth is that for experts this risk has never lost its urgency. Last year, the director general of the World Health Organization (WHO), Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, stated with respect to influenza that “the question is not if we will have another pandemic, but when.” In recent years, the world has been shaken by two Ebola outbreaks and the emergence of new diseases such as Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) and Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS), in addition to several flus. But which virus will be responsible for the next major pandemic? And when it arrives, will we be prepared to fight it?

Last September, a report by the Global Preparedness Monitoring Board (GPMB), a body created by the WHO and the World Bank to promote preparedness for global health emergencies, released its annual report, warning of “a very real threat of a rapidly moving, highly lethal pandemic of a respiratory pathogen killing 50 to 80 million people and wiping out nearly 5 percent of the world’s economy.” And “the world is not prepared,” this entity warned.

The most dangerous candidate virus

The GPMB’s forecast outlined one of the features of the profile that experts often attribute to the virus responsible for the next pandemic. “The most dangerous candidate virus for a pandemic is one that spreads well and relatively quickly. A respiratory virus fits that description very well,” University of Queensland (Australia) virologist Ian Mackay explains to OpenMind.

For his part, infectious disease specialist Amesh Adalja, an expert in pandemics and biosecurity at the Center for Health Security at Johns Hopkins University (USA), adds another feature to the imagined respiratory virus: “It will also likely be genetically an RNA virus given their mutability is higher than DNA viruses allowing them more ability to adapt to new hosts,” he tells OpenMind.

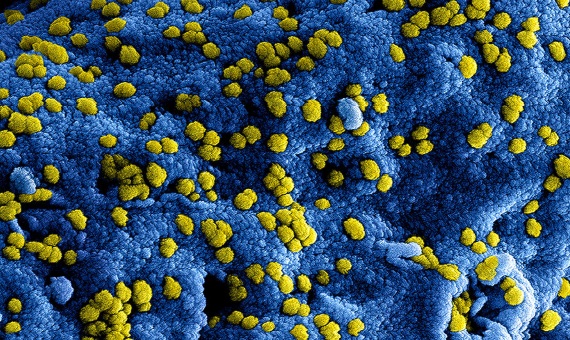

And it’s no coincidence that respiratory RNA viruses are some of the ones that have caused the most concern in recent years, like the different types of flu, along with three others that have something else in common: SARS, MERS and 2019-nCoV are all coronaviruses. And according to Texas A&M University (USA) virologist Benjamin Neuman, who has been studying coronaviruses for more than two decades, there are reasons why these particular agents are especially insidious.

“Coronavirus genomes are a little larger than those of other RNA viruses, and with that extra bulk comes an enhanced repertoire of tools to enter and disable a host,” he tells OpenMind. Thus, Neuman continues, they are particularly versatile viruses with a defence mechanism comparable to that of much larger DNA viruses, such as smallpox. “They are very successful at playing hide and seek with the immune system, and this allows them to persist in a person for weeks when other cold and flu viruses are detected and cleared in days.” This persistence, in turn, makes it easier to spread to other hosts.

Transmission by bats

In addition, these viruses are very numerous in animals. “We know that there is a big reservoir of coronaviruses out there – bats, in particular, seem to contain a wide variety of viruses that have the potential to spill over into people or other animals,” Neuman adds. Bats have been implicated in some of the most recent zoonoses, infectious diseases that are transmitted from animals to humans, such as Ebola and SARS, and it could also be the case for 2019-nCOV, but University of East Anglia (UK) conservation biologist Diana Bell, an expert on animal reservoirs of emerging zoonoses, warns OpenMind, “it’s important not to jump to premature conclusions before scientific evidence is available for the latest coronavirus.”

The truth is that coronaviruses related to SARS have been found in bats, and 2019-nCoV falls into this category; one of those found in these mammals has a genome 96% similar to the new virus. “Although they are not identical viruses, they are definitely of the same species,” emerging infectious disease specialist Linfa Wang of the National University of Singapore and Duke University’s Institute of Global Health told OpenMind. Wang has been studying bat-borne viruses for more than 20 years, and in 2005 led the team that identified bats as reservoirs of SARS-like coronaviruses.

According to Wang, it is not easy to determine why bats are such frequent players in emerging zoonoses. “Our current working hypothesis is that with almost 100 million years of adaptation since the ancestral bats acquired flight capability, bats as the only flying mammal have developed a quite unique defence/tolerance system which is different from human, mouse and other land mammals,” he explains.

However, Wang says that we shouldn’t “demonize the bats.” In fact, he stresses, “viruses and bats have lived together peacefully for millions of years,” and what has broken this balance, causing these viruses to jump into our species, is human activity: “environmental encroachment, intensive farming, wildlife trade and consumption, etc.”

Outbreaks in markets with live animals

This is the case for coronaviruses such as SARS and 2019-nCoV, whose original outbreaks in Guangdong and Wuhan, respectively, have been located in markets where live animals of very diverse species are sold in close contact with each other. Bell and other conservation experts insist that this trade not only damages biodiversity, but is also a constant threat to human health. Tackling these activities, they say, is one of the main preventive measures to avoid future pandemics.

But while there is still a long way to go in prevention, at least preparedness in response to these threats “has improved significantly in the past decades,” says Adalja, which he attributes to improvements in technology and to better recognition of infectious threats. “The novel coronavirus response is an example of this as evidenced by its rapidity and the largely proactive response of many countries.”

But the problem for Mackay is that not all countries have made equal progress in this preparation: “Some will suffer disproportionately should a new virus suddenly emerge,” especially countries that “do not have the health infrastructure and wealth to create it.” And in any case, he adds, cases like the new coronavirus are a clear indication that the tools are still limited when it comes to containing a rapidly spreading virus. Moreover, add the experts, it is essential to never to let down your guard, since preparing for the next major pandemic is a work in progress that requires constant vigilance and a continuous flow of resources. Because, as Neuman suggests, “it’s easy to predict pandemics, but very hard to predict them correctly.”

Comments on this publication